December Thread Spinner 39 -- On Empowering Natural Beauty - Lorna Elizabeth

November Thread Spinner 38 -- To Walk A River - Annabel Abbs

October Thread Spinner 37 -- The Art of Belonging - Dawood Qureshi

August Thread Spinner 36 -- The Story Behind the Story - Gulara Vincent

July Thread Spinner 35 -- The Saints in My Attic - Sheena Graham-George

June Thread Spinner 34 -- Wicked Women, and moving out of lockdown - Elinor Randle

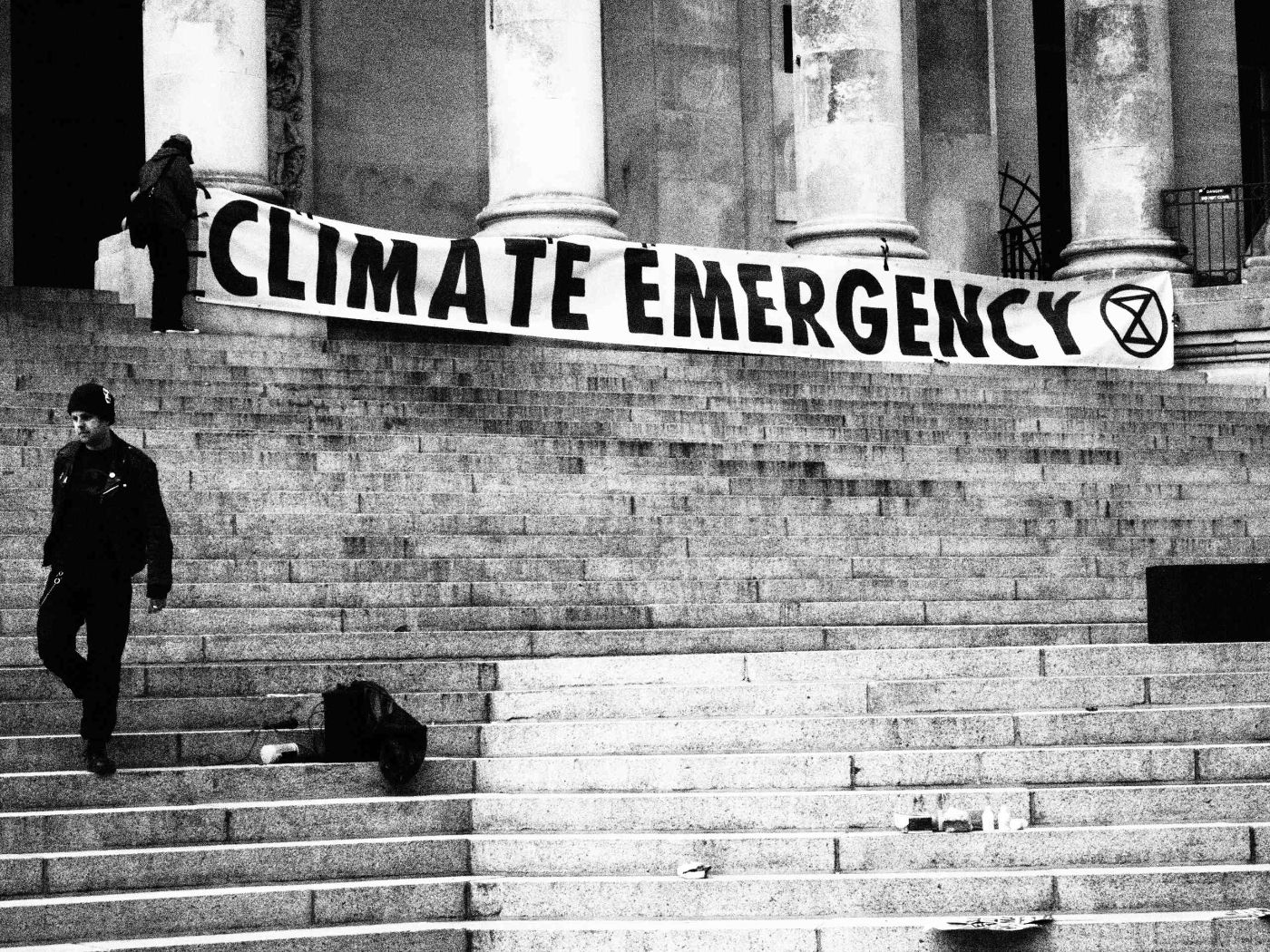

May Thread Spinner 33 -- The Nature of Class - Natasha Carthew

April Thread Spinner 32 -- The Lonely Isle -- Cal Flyn

March Thread Spinner 31 -- These Lengthening Days -- Alice Tarbuck

February Thread Spinner 30 -- Honouring Our Ancestors -- Raine Geoghegan, M.A

January Thread Spinner 29 -- Home: becoming a naturalist in residence -- Stefanie Rixecker

Text & images by Lorna Elizabeth

Cumbria, UK

December 2021

Throughout history, the human race has always been fascinated and inspired by the natural world. From Shelley’s ‘Mont Blanc’ to Monet’s water scenes, the abundance of what nature has to offer is astounding. For me, a huge source of inspiration can be found in the imperfections of the world. As a society, we are so fixated on achieving perfection that we tend to overlook the fact that we can openly accept and celebrate imperfections in nature.

When it comes to accepting flaws within ourselves, however, we find it somewhat more challenging. Within my own work, it’s these “imperfections” that I want to normalise celebrating.

We are all born unique and everyone’s version of perfection differs. We are all guilty of comparing ourselves to others and often feel like we come up short, especially in our developmental stages, just as we are starting to learn our personal identities. I like to think that my job plays a small role in helping people connect deeper to their own unique recognition and help them applaud that. I very much use nature to achieve those goals.

There’s a lot of things I consider when planning an outdoor shoot. It’s a big misconception that blue skies and sunshine are the ideal for photography. The reality is, we want it overcast and moody, and maybe a bit breezy to help that dress flow and give some drama.

I’m not chasing perfection and that’s where every creative choice comes from during my projects. Just like the mountains that often feature in my images, it’s the jagged crags and the pitted scars on the landscape that make for more interest and intrigue. It’s those that the ramblers and adventurers want to explore. How bland a world where everything above us was a grassy knoll! This is how we should view ourselves. We are all individual and should be treated as such.

I meet every shoot with the client’s wishes and comfort level at heart. This has led me to work at so many different locations and in so many different genres. In doing this, the result is always a truly unique set of images tailored to the individual which could never be replicated. You could turn up with the same model, same outfit and same poses in a location multiple times but you can guarantee that each image won’t look the same, and we have nature to thank for that.

Mother Nature offers what she does on the day, and we work with it. This is something that I am very proud of within my work. Each image is a unique timestamp of that exact day and time, and unique. It’s not just me creating the art; it is a collaboration between myself, the client and the environment.

I often work on projects which aim to send a positive message to empower females. My ‘White Shirt Project’, shot a few years ago, involved inviting twenty different females of all shapes, sizes and ages to come along and be shot wearing the same white shirt. The one rule was that no Photoshop was allowed. I needed to promote authenticity to remind young females that the glossy images you see in magazines aren’t always a true representation of women in society.

My next project, happening this December, is a group shoot with five volunteer women, all of different shapes and sizes. The message is to promote body confidence and to highlight our strengths, dismissing the deplorable numbers that found on clothing labels.

After all, the most beautiful thing a woman can wear is confidence.

Lorna Elizabeth was born in the Lake District. Her creative journey has led her to become photographer, specialising in female empowerment shoots. She has had work featured in galleries across the North West UK, and won Photographer of The Year 2018 at The Newborn & Portrait Show, Coventry.

Since studying for her BA (Hons) Fine Art, Lorna has developed a personal creative style that brings together a marriage of art, photoraphy, and nature, working with women to explore strong visual narratives that reflect their own personal journeys.

(All images reproduced with kind permission by Lorna Elizabeth)

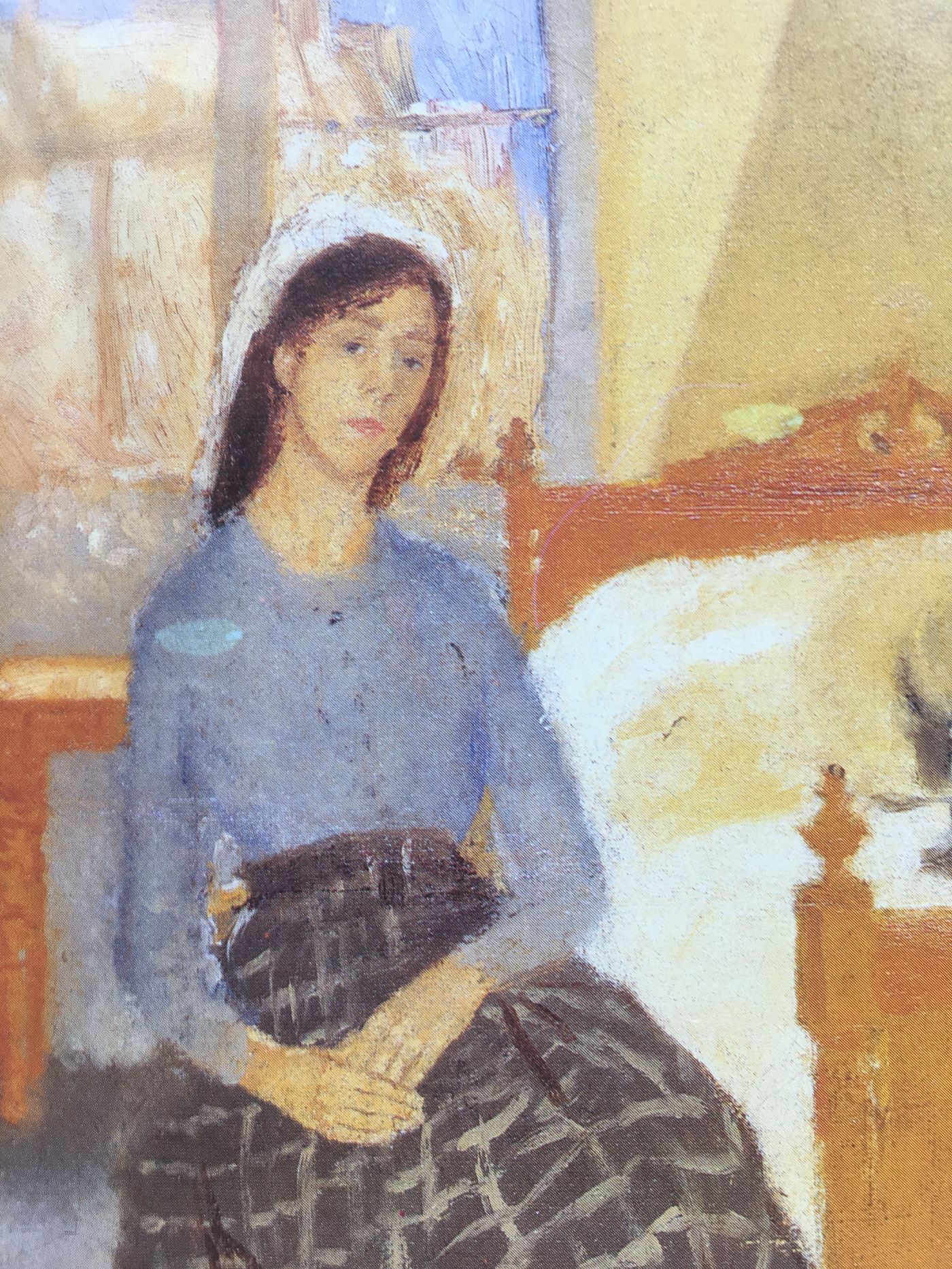

By Annabel Abbs

London/Sussex, UK

November 2021

To fall in love with a river? Impossible! Ridiculous!

Or so I thought. Until three years ago, when I set off to walk from Bordeaux to Toulouse. I planned to walk for a hundred miles, following the River Garonne from its Atlantic mouth near the port of Bordeaux to its decisive bend at Toulouse, where it veers south to its source in the Spanish Pyrenees.

I was following in the footsteps of the Welsh artist, Gwen John, and her friend, Dorelia McNeil – the woman who was to become her sister-in-law, wife of painter, Augustus John. In 1903, the two young women decided to walk from Bordeaux to Rome. Alone, unchaperoned and penniless, this was a radical, reckless decision. Augustus demanded that they take a gun. They refused.

With their belongings on their backs – which included easels, paints, brushes and paper, so they could sell portraits as they went – they set off on a journey that was to change their lives irrevocably, in ways they couldn’t possibly have foreseen. But isn’t that one of the great thrills of following a river?

I was walking the same path in a bid to understand what drove women of the past to make such extraordinary journeys on foot. Tired of reading about the great bipedal adventures of lone enraptured males, I’d decided to write a book (titled Windswept) about the little known female walkers of the past, the women who had roamed wild and uninhabited places but whose escapades had been omitted from all those anthologies and walking books written by men. I was tired of scanning library and bookshop shelves and finding the same old walking men (you know the ones). And so I’d gathered up a group of past women, picked out seven, and identified their pivotal routes. And now I was walking as they had.

Well, not quite. They walked without lightweight waterproof clothing, bras, mobile phones, GPS, energy bars or backpacks with padded straps. I’m not sure Gwen and Dorelia even had a map.

Herein lies the joy of following a river. No navigational skills needed! Indeed, many of the women I researched chose coastal and river walks for exactly this reason: less chance of getting lost.

The River Garonne route is unusual, for much of it runs alongside a canal. Which meant that I was often walking along a strip of land with the maverick, churning Garonne on one side and, on the other, the domesticated, becalmed Canal de Garonne. The symbolism wasn’t lost on me. And I doubt it was lost on Gwen John either. It seemed to me that this watery landscape mirrored the truth of my own divided life.

The canal is now largely recreational but when Gwen walked, it was hugely industrious – buzzing with barges and business. Diverted from the rebellious River Garonne, the canal had been domesticated by men, and was managed by a series of locks. Meanwhile the River Garonne was known for bursting its banks, flooding villages, re-carving its wild and foaming path. Even today, costly projects are afoot to curb the turbulent, spilling waters of the Garonne.

Walking day after day beside these dramatically different water sources became a rich source of ideas. Bathed in an abundance of shivering reflections and endless light, I seemed to enter a different universe. Apart from a purple-great heron that greeted me every morning, both canal and river were usually deserted. For the first time in my life I felt euphorically alone, just as I imagined all those lone enraptured males had felt. This too set my mind alight.

Hardly surprising then, that I became obsessed with the river. After a few days of walking, I’d planned a rest day a few miles off my river route. I’d chosen an idyllic town of yellow stone, booked a hotel and located the best patisseries. But when the day-of-rest came, I felt such a deep visceral longing to be beside ‘my’ river, I changed my plans. What was a plush bed and a freshly baked croissant next to the constant joy of my wondrous watery companion? I tried to enjoy the little French town, of course. But it was impossible. Its hustle and bustle made me yearn with even greater ferocity for my leafy river path, my silent heron, my lunches of wild green figs and watermint. And all that endless dancing light.

No wonder Gwen John spent the rest of her life seeking out water, longing for its intoxicating company. I returned to my London home and took to pacing the banks of the Thames. Now I visit her every day. Just to be with her. And it’s enough.

Windswept: Walking the Paths of Trailblazing Women, is out now, published by Two Roads.

Annabel Abbs is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Joyce Girl, tells the story of James Joyce’s daughter, won the Impress New Writer Prize, was translated into 10 languages and is currently being adapted for the stage. Her second novel, Frieda: The Real Lady Chatterley, was a Times Book of the Year 2018, and was translated into seven languages. Her memoir and history of wild walking women, Windswept, was published to great acclaim in June 2021. Her next novel, The Language of Food, tells the story of poet and cookery writer, Eliza Acton, and has been optioned by CBS Studios. Annabel has a degree in English Literature from UEA and is a Fellow of the Brown Foundation. She grew up in Wales but now lives in London and Sussex where she spends her time cooking, walking, reading and writing.

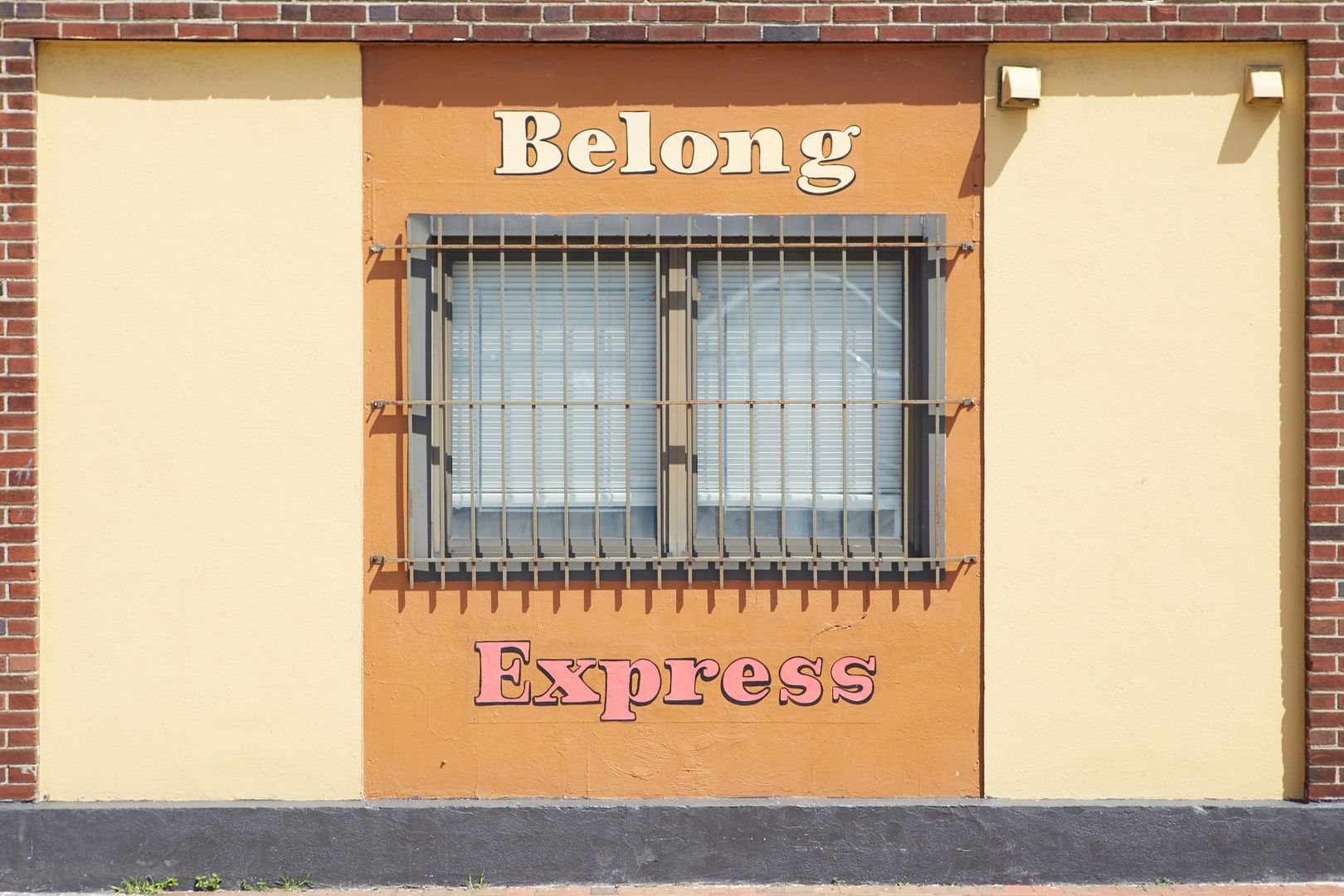

By Dawood Qureshi

Portsmouth, UK

October 2021

Belonging.

Be-Long-ing.

Belonging.

Belonging.

Belonging.

Belonging.

Like any word, the more I say it, turning the letters around in my head constantly and depositing them in various jumbles of ineloquence, the less this becomes an actual word, and the more it trails off into nothingness. The strange thing is the same can be said about the meaning. The more I think about it, the less it becomes clear what It actually is.

What does it mean to belong?

Where must one belong?

Must you belong?

Can you ever truly belong?

Why do we want it so badly?

I feel as if I’ve been running around a maypole my entire life, and the central post is this word. Belong. Everything I’ve done, and indeed everything most people do in their lives, sits parallel in some form or fashion to this feeling. I call it a feeling because it is very much an emotional package. We wish for it, we crave it, we are attached to the unquenchable thirst of partnership, and the want of relatability.

It all started when I was very young.

That’s how most tales begin isn’t it? Romances. Glorified war memorials. Desperados. Thrillers. Comedies. They all start at the beginning. We learn everything we are as we grow, but the tools we are given to hack out an existence are first discovered when we are soft-shelled things, just beginning to have some colour applied to our fresh, white (or in my case, brown) canvas.

I was a rather strange little thing. And I say that in a completely positive sense. Long hair down below my shoulders, small oval glasses forever pushed up the bridge of my nose, as I explained it is PERFECTLY normal to devour the Wikipedia page on Australia’s wildlife at the breakfast table. I wore clothes I can confidently suggest now deserve the title of “home-spun, overall chic”, and I spent many an hour goggling over a tweed suit, or a silken bow tie.

Many of you who know me will read this and react with a simple, “well, you didn’t change that much then did you!”.

Ok, fine. A lot is the same. But I did change. Mindset mainly, but we’ll come to that later. The point is, I didn’t belong. At least, I didn’t belong many places I was SUPPOSED to belong. There weren’t a lot of aisles that had the correct labelling to put me on a shelf there, and I dare say there are even less now.

We are taught with quite a terrible, cut throatedness, that in order to thrive, we simply MUST belong. We are taught where to belong, and how. There are manuals dedicated to it. Movements upholding rituals and laws pertaining to it. People are killed over it, and some are hounded down until they surrender to its dull sheen. Some would say it controls how we live. That constant reminder of “the movement”, of “purpose”, “goals” -- are they not all connected in some form or fashion to the idea of Belonging?

But what does it mean to belong?

I can attest first-hand: it’s got quite a kick to it. You can talk about the highs of life till the cows come home; food, money, drugs, sex, whatever -- but you will never beat security. The euphoria that accompanies the comfort of security rises so high above the rest, it is often forgotten in our great scramble for the others. Everyone on this planet craves security -- whether it be basic human rights, financial, emotional, social -- it fundamentally undercuts every other feeling and thing on earth, because it gives you choice, and choice equals freedom. And my god, do we become addicted to the concept of freedom.

I’ll try not to talk in badly structured riddles for the entirety of this. We’ve established that we crave belonging, because it is essentially a suit of armour in the form of security: in order to belong, we must find a group of like-minded individuals, and together realise a common goal/goals, which we will then accomplish together via (preferably) friendship and loyalty, or (perhaps less preferably) desperation, and/or force. We are now all needed, or at least feel as if we are needed. The machine cannot function without all its cogs, and your society will protect you, if not out of love, then out of a simple need of your services.

You feel wanted. Needed. Essential.

Once security has been established, time can now be dedicated to other exploits; you can learn to sky-dive, or perhaps become quite adept at dismantling and repurposing petrol lawnmowers. I’m sugar-coating the whole affair, but you get the gist; freedom is delicious, and it would seem that it is the aftertaste of a quick swig of Belonging.

So, we want to belong but it only really works if we are told where, and how to belong…right? You can’t have a machine with cogs jumping around willy-nilly, talking about what they want, wearing what they want, and generally acting as if they’re the lead-cog. The machine would collapse, the security would be no more, and the flowers would all die. No, no, no! We need some efficiency around here. Uniforms, speech lessons, laws: Conformity.

Conformity doesn’t have the same, comfortable, hot chocolate-tinged zeal to it as Belonging, does it? Yet, they’re of a very similar origin. Conformity is to Belong, but it is to belong at a price. A quick google, and we have,

“Conformity, the process whereby people change their beliefs, attitudes, actions, or perceptions to more closely match those held by groups to which they belong or want to belong or by groups whose approval they desire”.

So Conformity is to Belong, via Change -- but surely that can’t be right? Belonging is security, it’s nice, it’s warm, it’s a way to be able to follow your petrol engine tinkering exploits. Surely, the whole point of Belonging is to find somewhere you fit in, not to rip the face off your personality, and crudely sew on a guise, in order to be seen as a more manageable entity?. Unfortunately, this is the most common way we are taught to Belong.

This society is born of smooth efficiency. We are taught to subscribe to that efficiency in order to climb the ladder, and ultimately, by Conforming, and forcing ourselves to Belong, we are carved into the cogs of a machine that cares not for the real face beneath the cleverly sewed-on joker mask...

Whew. Had to stop for a minute.

We want to belong because we want to feel safe, and from a young age we are taught there are only certain ways to belong, so that we may be allowed to feel safe.

I’m trying not to rant, I promise. Or write a manifesto. But, it’s hard because what I’m essentially trying to tell you, is that the Art Of Belonging is a façade.

The sooner we understand that our happiness and wellbeing is dependant not on the ability we have to belong, or the ability to serve, but instead on our ability to love who we are, however weird and wonderful that inner-self may be, the sooner you can stop listening to me ramble, and get on with raising spiders or whatever (that’s a personal one).

Conformity is an aide to efficiency, and frankly, humanity is far too complex and beautiful to need to be reduced to efficient machines.

Trust me. I went the long way round. I was a weird child. I grew up learning how to conform in order to thrive. I went through countless changes. I came out. I wore weird clothes. I had to unlearn everything, and relearn some things. I lost people, and gained a whole lot more. I got angry, sad, happy, tired, anxious. And I’m only 22.

Your safety and security shouldn’t have anything to do with the ability you have to mask who you really are, and subscribe to a system you have never even had a hand in cultivating. The ability to understand what makes you happy, in a healthy and tender fashion, that’s a real means to safety and security.

You Belong when You Choose to Belong.

Dawood Qureshi (they/them) is a Writer, Wildlife-film maker, Freelance Journalist, Activist, Marine Biology graduate and Television Researcher at BBC Natural History Unit. They have written for multiple magazines and blogs, on topics ranging from natural history and conservation, to identity, diversity and political history. They are a keen speaker, using this as a way of communicating and educating, at science festivals and other events, and also do work as Ambassador for the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, and as Engagement Officer for the nature organisation AFON. As a writer, storytelling has always been core to everything they do, and it is a dream to explore both the written and physical world for as long as they are alive.

Twitter: GoWildForBees

Insta: wildheartwithacamera

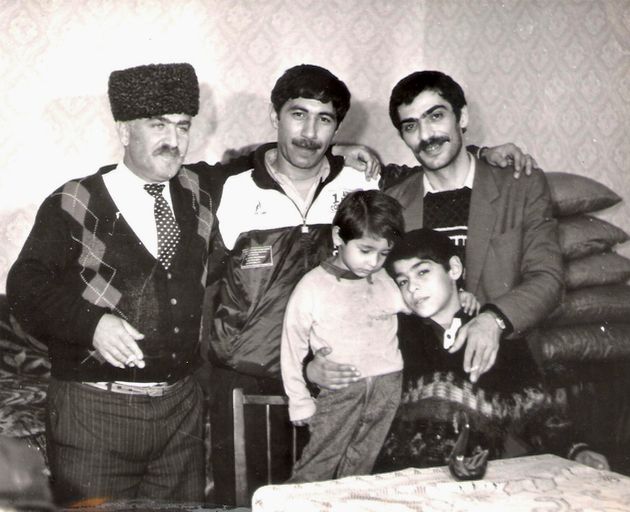

By Gulara Vincent

Devon, UK

August 2021

In November 2011, a mere two months in my new permanent post as a law lecturer at the University of Birmingham, I had an epiphany. One rainy evening, I was working in my office, marking a big pile of essays, when I heard a voice in my head: I was here, in this life, to teach and to write, but law was not the right content. By then I had been teaching law for 10 years. I tried to ignore the message. There was nothing else I could do, I reflected gloomily as the first term drew to its close.

In December 2011, I decided to take a trip to Azerbaijan where I originally come from. I had a property to sell and family to visit there. More importantly, I was on a mission to find my father’s grave. My parents were divorced when I was a mere two week old baby. I had never met him. Despite trying to heal this open wound for years, nothing helped. Perhaps, finding his grave could bring some closure, I decided.

I travelled to my hometown Ganja on 18th of December and had a long walk in a local cemetery which sprawled indefinitely, peering at names and images on marble gravestones.

I couldn’t find his grave.

Disappointed, I went to buy my return ticket. As I walked through bustling city centre, I suddenly remembered something my mum told me when I was a child.

‘You have an auntie. Her name is Tahira and she lives behind the central department store.’

On an impulse, I went knocking on people’s gates.

‘Does someone named Tahira live here?’ I asked, over and over again.

Eventually, someone pointed me to the gate I might have been looking for. Standing in front of rusting brown gates I wondered whether it was too late to turn around and walk away. What if she hated me? What if she rejected me? She did not know me after all.

An old skinny man came to the gates. I asked the same question I had been posing for the last hour. Yes, he nodded.

Impossible, I thought to myself.

‘Did she have a brother called Nizami?’ I asked.

He nodded again. My throat dried up.

‘Can I see her?’

‘Today is not a good day. She is busy. Come back tomorrow.’

‘I will not be here tomorrow. I just bought my ticket. I have to see her now,’ I insisted, half-wondering whether I should run.

Reluctantly, he shuffled away.

A few minutes later a woman came to the gates. She was in her fifties, wearing a black dress. She pushed her dark hair off her eyes and peered into my face.

‘You look so familiar, but I can’t place you,’ she said.

‘That’s because we’ve never met before. I am your brother Nizami’s daughter,' I told her. I tried to keep my tears back. I was finally meeting my auntie at the age of 36!

'I just want to have his photo,’ I added hastily, in case she wondered why I decided to appear now.

Her response was completely unexpected. She hugged me tight and sobbed heartily. She said she had been waiting for this day for a long time. When tears subsided, she took me through to the house.

It got better.

It turned out that the family was celebrating her 58th birthday. The house was crowded with relatives on my dad’s side of the family that I had never met. The love I was showered in was like a healing balm on the part of myself that felt abandoned and not loved for years.

That day, I got two of my dad’s photos, and visited his graveyard.

Once I started writing, I couldn’t stop. It’s like my soul wanted me to tell my story. It came through in blog posts, live autobiographical theatre performance and finally, as the book, 'Hammer, Sickle, Broom - A Memoir of Intergenerational Trauma in Azerbaijan', set against the turbulent backdrop of the collapse of the Soviet Union and Azerbaijan’s transition to independence.

My big mission in life is to help people feel heard.

I do it in my academic work, by advocating for the rights of marginalised people. I do it in my own book, by giving voice to women in Azerbaijan, who may never be heard otherwise. I do it in my healing work, by holding a space for people to heal their fears, find their voice and have courage to express it in the world.

There is no better feeling than being part of that process.

Gulara Vincent is a bestselling author, associate law lecturer, and certified energy healer. She uses all these avenues to give voice to under-represented communities and is passionate about . I live in rural Dartmoor National Park in South West England, with my two children, where I tend the love of my life, and write.

By Sheena Graham-George

Orkney

July 2021

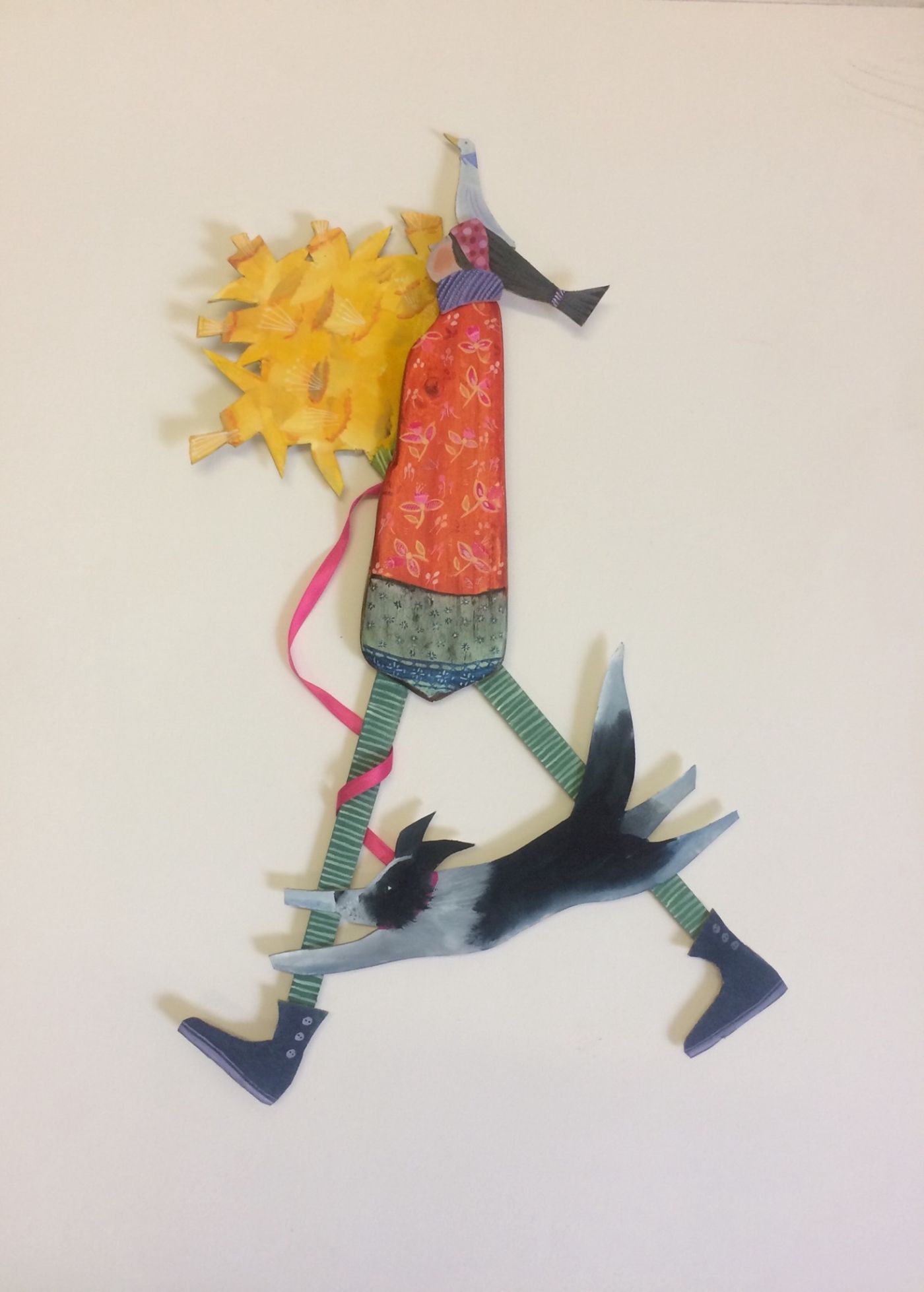

I am sat in my attic studio, the blue of an early morning midsummer Orkney sky peeping through the skylight. The floor is covered with my latest saleable creations crafted from driftwood collected from my beach rambles, and the covers of old pre-loved books. These are my Jumper Women – all crazy ladies festooned in patterned jumpers (a couple not oddly), cavorting with mad collie dogs, Suffolk sheep or large birds with blue spotted neckerchiefs; each figure meticulously painted in watercolours.

On my work desk sits After St Gertrude, in a red patterned jumper and green kilt, a large fat ginger cat smilingly benignly down from his perch atop of her black bobble hat. Her companion piece, After St Kevin rests on the studio floor – clothed in a multicoloured jumper, hand outstretched where a nest, complete with blackbird and little blue speckled eggs rests. She rubs shoulders with Hide and Sheep inspired by Saint Drogo, where several sheep peer out from a large bouquet of purple irises, and a further sheep emerges from behind the figure’s yellow wellington boot. Later this morning After St Bride will have a fairisle pattern applied to her bright yellow jumper and a flock of oyster catchers will eventually get attached to her long purple striped spindly legs.

I often feel as though I have two juxtaposed artistic personas which sit in opposition to each other, yet on closer inspection perhaps they do not. The appearance of Catholic saint’s names is a bit of a giveaway into my research practice which for the past 10 years has been all about the cillíní, the unbaptised children’s burial grounds found scattered throughout rural Ireland. These works are sombre in nature, yet through my installations, sound-work and socially engaged practice I have always tried to create work of beauty in memory of these individuals buried in these sites and their families. And this is perhaps where a link can be found with my driftwood women, the desire to create work which connects on an emotional level whether it is through bringing joy or solace.

My interest in either painting or highlighting the lives of women is another touchpoint. My most recent work for my PhD with Glasgow School of Art was the creation of a public sound-work, Requiescat, composed from the many audio interviews, field-recordings, and narratives I had collected in County Kerry over the years. The sole focus of the work was to raise awareness of the mothers who died in childbirth and were, we are told by oral history, buried in the cillíní. This group of women have over the years been sadly overlooked by many historians and academics and risk being erased from memory for good.

Over the last year, I have found myself turning to writing more and more as another creative medium in which to communicate. The threads of my work with the silenced mothers of the cillíní can be discerned in the series of essays I am slowly crafting. Each one is about different aspects of silence, its sound and texture, from that of dementia and loss which has engulfed my dad and our relationship, to the crowded-angry-memory-ridden-hurt silence between two friends in a car after an explosive argument, or the silence of listening to history trapped in the landscape of Flotta and the Silent Hut. Some of these pieces will sit alongside sound-works, like the one about my dad where I have created a short piece where he sings his old party song – The Inversneckie Grocer, as the sound goes on it slowly falls apart, becomes confused, with gaps, like his memory.

This afternoon, I will pack up my rucksack complete with laptop and notebooks and take the walk along the seafront here in the village before climbing the hill to look down on Scapa Flow and across to Flotta and the Hoy hills. From the top of the hill, can be seen a tiny white speck sitting high above the strand – this is my writing retreat for the summer.

A couple of years ago I bought an old 1980s caravan and converted it into a travelling gallery with painted tongue and groove walls, old patchwork quilts, woodburning stove and hand patterned painted exterior – very distinctive. This year with Covid restrictions making exhibiting in such a small space difficult, I have turned it into another workspace, free from the internet and other distractions.

But for now, I will go back to attaching a rather smug looking white cat to St Gertrude’s legs and try and figure out whether St Brides' boat is going on her head, or out the window!

For the past 19 years my home has been in the far-flung archipelago of Orkney where I work as an artist.

By Elinor Randle

Liverpool, UK

June 2021

Based in Liverpool Tmesis Theatre create, develop and share passionate and playful physical theatre through performance, participation, a training company and an international festival- Physical Fest.

Tmesis are a female-led company who are currently making work with, for and about women, including the recent: Wicked Women, celebrating extraordinary women who changed the world, a 6-month Creative Development Course for young women, Lone Women film series, and ‘Mothers who Make’ a monthly group for mothers who are also makers.

A while ago, after many conversations I had with Claire our producer, we decided we would change part of our company focus, to working with and supporting female artists. We had been doing this anyway in various forms for many years, but opened our eyes more widely to the, still huge gap in opportunity for, and confidence in many women. We started initiatives such as hosting the Liverpool Hub of Mother’s Who Make a growing national initiative aimed at supporting mothers who are artists where every kind of maker is welcomed, and every kind of mother. We created a new 6 month creative development course, Wicked Women for young women who are starting out in the arts, helping them navigate what can be a very daunting industry. These networks of support have been invaluable, especially for people over the past year. It has been beautiful to see relationships formed, work created and confidence growing, literally webs being spun and strengthened!

Wicked Women’s Guide to - a project our last cohort created together during the last lockdown: https://www.tmesistheatre.com/projects/wicked-womens-guide/

Coming out of lockdown I’m now working on our festival, Physical Fest, it’s all had to happen very fast which is a bit of a shock to the system, but it is also very exciting to be back in a rehearsal room and to feel the magic and value of live work and connection.

The festival brings physical workshops, performance to Liverpool, and we normally host a lot of international work, which this year we can’t. I decided to make a site-specific show especially for the festival, I really felt I wanted to get out of the ‘black box’ theatre and now make work in a bigger variety of spaces, and again it gives work to local artists and it also involves our training company.

Lucy Hopkins' Ceremony of Golden Truth - a collective act of golden manifestation, sacred laughter bath and ceremonial mess-about orchestrated by a preposterously dazzling goddess. Very golden, mostly truthful. Sacred as holy hell.

Barely Visible grapples with the complicated terrain of female queerness by asking what will happen if gay women continue to live in the shadows.

We are making a piece in a beautiful Art Nouveau hall within a church, the Albert Walker Hall, a hidden gem which has recently been restored by Heritage Lottery. I’m exploring the concepts of memory and nostalgia, what and why we remember, what places mean to us, how they live on and hold stories within their walls, the traces and imprints people leave behind.

We are continuing to support female artists at the festival, through a bursary and mentoring programme, which enables female physical theatre artists to create new work: https://www.tmesistheatre.com/physical-fest/femalebursary/

My fingers and toes and firmly crossed that all our live events will be able to take place and I breathe a sigh of relief that we have survived the past year and made new connections and new work.

Elinor is Artistic Director of Tmesis Theatre, acclaimed UK based physical theatre company, and Physical Fest (Liverpool’s International Physical Theatre Festival).

Elinor has performed in or directed, all of Tmesis Theatre’s past productions, touring nationally and internationally for the past 18 years and specialises in creating devised ensemble based theatre.

Tmesis Theatre have received critical acclaim for their dynamic and unique physical theatre and won the award for ‘Best Choreography at the United Solo Theatre Festival, New York 2016.

Elinor also works as a lecturer at LIPA (Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts), is a trained yoga teacher and has worked as a director/ movement director for many companies nationally and internationally including 20 Stories High, Box of Tricks, Peepolykus, Leeds Playhouse, Fadunito and the Everyman and Playhouse.

By Natasha Carthew

Cornwall, UK

May 2021

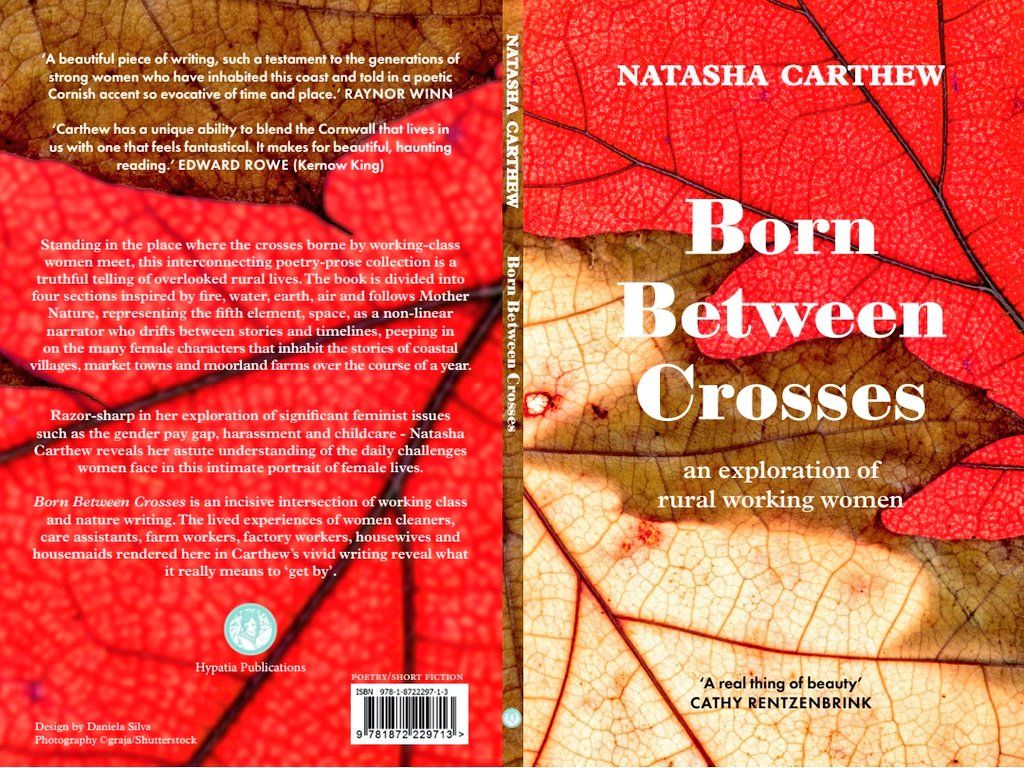

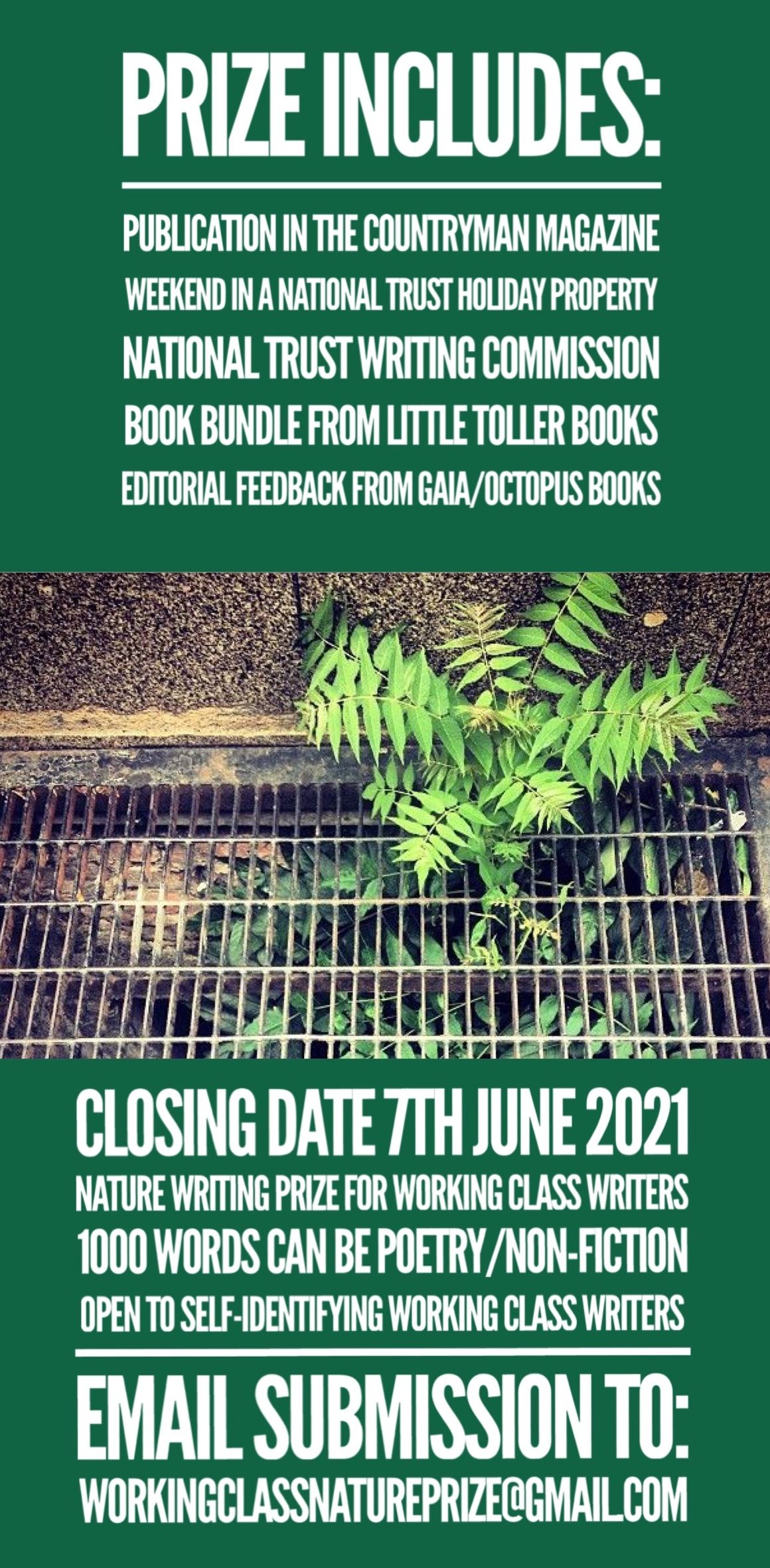

There are two stand-out moments for me that are happening this Spring, one of which is the publication of my new book BORN BETWEEN CROSSES which has been a very personal, heart-wrenching journey and the other is an interconnecting expedition that links writers nationally, the Nature Writing Prize for Working Class Writers.

BORN BETWEEN CROSSES, my eighth book, is a collection of prose-poetry that celebrates the work of rural working-class women, which has just published with the award winning Hypatia Books.

Standing in the place where the crosses borne by working-class women meet, my interconnecting collection is, I hope, a truthful telling of overlooked rural lives. It took me three months to write this book, but a lifetime to collect the tales of my childhood; these stories are not just my experiences but those of my Mother, my Grandmother, and the hard working female community that surrounded us on our small rural council estate in Downderry, our village on the south coast of Cornwall. Whilst writing the book, I could hear their voices shout to me from upstairs windows, could hear their singing from the doorsteps to the music that was always playing, their whispers came to me on the wind, asking, ‘remember me.’

The book is divided into four sections inspired by fire, water, earth, air and follows Mother Nature (the ultimate Mother), representing the fifth element, space, as a non-linear narrator who drifts between stories and timelines, peeping in on the many female characters that inhabit the stories of coastal villages, market towns and moorland farms over the course of a year.

'A beautiful piece of writing, such a testament to the generations of strong women who have inhabited this coast and told in a poetic Cornish accent so evocative of time and place’

RAYNOR WINN - Writer

It’s an exploration of rural working women and is an incisive intersection of working class and nature writing. The lived experiences of women cleaners, care assistants, farm workers, factory workers, housewives and prostitutes rendered here in an interconnecting collection of prose-poetry that address the challenges that relate to working class women from a rural, low-wage ‘work’ perspective and I’m really pleased to announce that I will be touring the UK and Ireland with BORN BETWEEN CROSSES throughout 2021 (please see tour poster.)

It’s really important to me both as a reader and a writer, that stories are told from a working class perspective and that is why last year I set up The Nature Writing Prize for Working Class Writers, a literary prize to break down barriers to nature writing and what is perceived as a nature writer.

The prize, which is free to enter, encourages self-identifying working class writers from all over the UK to dig deep into the dirty world of nature writing, whether they live in the country or in towns and cities.

I’m often asked why a Prize for Working Class Writers is so important in literary culture and my first answer is always that working-class voices are increasingly absent from publishing and the media, especially nature writing, but I hope this prize is slowly changing that.

It's important to me that this prize is accessible, breaking down barriers and providing a platform to celebrate the diversity that exists in nature writing (poetry, field notes, memoir, travelogue etc), celebrating nature whilst providing a platform for underrepresented writers. Nature writing exists because we as individuals want to understand our own engagement and our place within it. It decentralises us and reminds us that we are not the only focus or thing of importance on the planet.

The best nature writing conveys a clear sense of place and focuses on the natural world and our human relationship with it.

I set up the prize to burst the stereotype of what it means to be a nature writer and to celebrate the diversity of authentic voices in our country, the kind of working class voice that doesn't just come from the country but the towns, cities, housing estates, parks and the overlooked landscapes like industrial, train tracks, wasteland, everywhere.

The Prize includes:

• Publication in the Countryman magazine

• Editorial Feedback from Gaia/Octopus Books

• A Weekend’s stay with National Trust Properties

• Paid opportunity to produce a piece of nature writing based on their NT stay

• A selection of Little Toller Books of their choosing

To Enter, please send up to 1000 words to: workingclassnatureprize@gmail.com

Closing date: 7th June 2021

Natasha Carthew is a working class Country Writer from Cornwall who famously has written all her books outside. She has written two books of poetry, three acclaimed Young Adult novels; ‘Winter Damage’, ‘The Light That Gets Lost’ and ‘Only the Ocean’ (published with Bloomsbury) and her latest Adult literary fiction ‘All Rivers Run Free’ (published by Quercus/riverrun). Her new prose-poem ‘Song for the Forgotten’ published with National Trust Books in 2020, and her latest short-story features in HAG: Forgotten Folk Tales published by Virago Press October 2020.

Her new book ‘Born Between Crosses’ is a new sequence of Performance Poetry celebrating the working lives of Working Class Women, published with The Hypatia Publications in April.

Natasha has written extensively on the subject of both Wild Writing and what it means to be a Working Class writer, and how authentic rural Working Class voices are represented in fiction, for several publications and programmes including Writers' & Artists' Yearbook, The Royal Society of Authors Journal, BBC Radio 3, BBC Radio 4, The Guardian, The Dark Mountain Project, The Bookseller, Book Brunch and The Big Issue.

Natasha is Founder of The Nature Writing Prize for Working Class Writers and founder/Artistic Director of The Working Class Writers Festival - in partnership with The Festival of Ideas and sponsored by Hachette UK and Penguin Random House and Founder of the Nature Writing Prize for Working Class Writers.

By Cal Flyn

Orkney

April 2021

During the writing of my new book, Islands of Abandonment, I spent 24 hours alone on an abandoned island in the Pentland Firth, between Orkney and John O’Groats. Swona was inhabited by nine families at the start of the 1900s, but in the years after the First World War many left to make new lives on the mainland, or abroad. One family, the Rosies, stayed on for many decades. The last of the Swona Rosies departed for the nearest inhabited island, South Ronaldsay, in 1974.

Swona has remained more or less abandoned ever since, their cattle—and latterly, the descendants of their cattle—left to roam free across the island. Rose Cottage, the last inhabited house, has fallen into dereliction. Seals and terns and puffins have made the island their own.

Dropped at the crumbling pier by a local boatman, I was advised to spend the night inside one of the empty homes lest the cattle, now wild and distrustful of humans, trample my tent in the dark. Surprised and chastened, I explored the island, which at first felt strange and eerie and exciting, and then increasingly uncomfortable.

The Marie Celeste atmosphere of Rose Cottage — tablecloth on the table, tins in the larder, copy of the Press and Journal announcing the election of Harold Wilson on the side — left the distinct impression on having stumbled on the scene of some long-past disaster.

Outside, what once had been a tractor sank into the earth, rusted solid. A handsome wooden boat was pulled high from the water, but its stern had disintegrated to matchsticks. Behind the double gabled byre I found the cadaver of a cow stretched out across a slab, its bones bleached blonde and the flesh melting away.

I felt a creeping horror, and felt in my pocket for my phone — to call my partner, at home in Edinburgh. But it was long dead. Its battery drained away after the two nights I spent camping on South Ronaldsay, waiting out a storm.

I headed north towards a rocky headland and a ship’s beacon, leaving the ruins behind me. Sea views, I thought, would be soothing. But soon I stumbled into other creatures’ territory. Arctic terns had established a colony on the rough ground; at once I was surrounded by screams and clicks. Tiny birds with sharp pronged tails and needling beaks divebombed me until I fled. Great skuas lunged at me as I passed. I hugged the coastline, and set of a caterwauling among the seals that basked in the rocky bay.

This was no longer a place for people. Had I been in company, this pillar-to-post circumnavigation of the island might have been funny. But, on my own, my nerves were failing me. I felt shaky and strange.

I have worked a lot with horses, and know well the change in their behaviour when one takes them out alone. A normally calm, steady gelding might become nervous and twitchy, rolling his eyes at rocks and trees he passes every day in company without issue. Now, I realise, I know how they feel.

They are ‘social animals.’ That is, they prefer to live in groups. So, I think, are we. We might travel ‘alone’, work ‘alone’, live ‘alone’ in a house. But it is very rare to be so entirely without human contact, even for a 24-hour period. We too are social animals. I hadn’t appreciated that before.

When we sell horses, there are stock phrases we use on the adverts. ‘Good all-rounder.’ ‘Easy to box/shoe/clip.’ ‘Hacks out alone or in company.’

That last one: it’s me. I realise it now. Take her out for an hour, she’ll be no trouble at all. But she still needs a stable mate, a herd of her own kind.

Someone to talk to. Someone to wave to. Someone to draw strength from. I was an ass to think otherwise.

Cal Flyn is an award-winning writer from the Highlands of Scotland.

She writes long form journalism and literary nonfiction. Her first book, Thicker Than Water, was selected by The Times as one of the best books of 2016. Her highly acclaimed second book, Islands of Abandonment, is out now in the UK, and is shortly to be released in the US, Netherlands, Italy and China.

(image Cal Flyn - credit Nancy Macdonald)

By Dr Alice Tarbuck

Scotland

March 2021

I was born in March. March is the month of crocuses and stirring. It turns the heart to spring, but doesn’t the snow show its face, some years, as a little bite in the heel as we run into the light. Reminding us the Cailleach is still sweeping, stamping and muttering, not yet ready to shrink down into a stone, that will hold Winter’s cold safe inside it all year.

March is the month of waxing fat. It is Ostara. So many festivals in the pagan year have teeth, have cloaked darkness and long nails that draw ice and suffering down windows, but Ostara tells another story. Ostara is the brimming hopeful dawn of spring, who unfolds out of Winter’s hand, radiant and growing. Ostara, as a goddess, is a dawn-bringer. She is linguistically a friend of Aurora, of the first rays of the morning sun. She is growth, abundance, the hare with its magic trick of fertility. She is the becoming of every green thing.

As a goddess, Ostara may, of course, be an invention of the Venerable Bede, but who are we to doubt the truth that sits inside her, the networked connections she makes outward. A goddess is like a forest, a network of care. A deity is nodal, all web and weave, and covers vast tracts of land, of history and of aspect. How else can they be? Can we not meet them, in the same way that we can walk to the snowline, gazing up to the peaks above, and not know the extent of its spread, or its continuous depth?

And who could, having sat in the cold cave of winter unrelenting, not find inside March’s lengthening days the seed of a goddess, anyhow? A growing and lengthening that feels like it might be strong-thighed and supple. Today is the final full moon of winter, and it is strong. I can feel it in my body, threading silver through my blood, pulling at the water of me.

At this time, at my birthday time, my skin starts to be the alive thing it has ceased being throughout winter. I long to get cold, the wind feels mischievous. I put my face in dew, even though the dew is half-frost. I turn tarot cards and my thoughts and eyes turn outward again. My skin goes from being that-which-shrinks-backed to being covered with receptors. Just entirely furnished over with seeking. I want velvet and tree bark, I want skin and teeth, I want the prickle of the hairbrush and the song of sugar on the tongue. I want, want, want, and that is Ostara. She is the throated joy of doxology, of the praising of the day that rises for us. Whoever she is, I hope that this March she comes to you, in the warm breeze or the last spread of snow, in the final frost or the cherry blossom, and offers you the fulness, the light, the renewal, the hope.

Alice Tarbuck is the author of A Spell in the Wild: A year (and six centuries) of Magic, published by Hodder. They are an award-winning poet, and teach Toil and Trouble witchcraft courses with Claire Askew.

(Image credit - Jamie Drew)

Text & images by Raine Geoghegan, M.A

Malvern Hills, Worcestershire

February 2021

It’s a cold January day. I am sitting at my desk. In front of me, a candle is lit and on the low window sill are photographs of my family, some living, some not. The starting point for any piece of writing is usually charged with a little trepidation. I ask myself. ‘Which thread do I want to weave?’

As I gaze at the flickering candle I sense a feeling of deep satisfaction as I reflect on my path over the last twenty five years. It was then that I first fell ill with ME/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, having already been registered as disabled after a serious fall down the stairs. Change transforms our lives and that includes change that we may not welcome. My path has been one of deep loss but also of renewed hope. Having been forced to give up my work as a dancer/actor/theatre director and workshop facilitator I turned to writing. At first I wrote short invocations to the Divine Mother which were later recorded and put onto a CD. I wrote poems and prose about the illness I was experiencing, the intense fatigue that floored me over and over, and pain, how it burned, how it fizzed in my body. In November 1996 I wrote in my journal:

‘How do we begin to take steps to heal ourselves when we hit rock bottom?

We breathe. We look at what we can do, not what we can’t.

We take one small step, then another.

We invest in our future by planting seeds of hope and courage.

We do it our way and we keep it simple.

We hold the intention of becoming whole and well in our hearts.

We stop trying to control everything instead we learn how to trust our mind, body and soul.

I also turned to my ancestors for help. I remembered a workshop that I had attended on ‘Healing the Ancestral Line’ some years prior to my accident. I came to understand that healing was reciprocal. I healed them and they healed me. The more I engaged with my ancestors, questioned who they were, what they did, how they looked, the more I sensed an energy that strengthened me. It healed me. It didn’t take away the illness or disability but it transformed them into something that I could live with, accept and learn from. Writing too had a transformative effect and helped me to make sense of the world and my place in it. I began writing about my Romany family in 2017 after my mentor suggested it. Once I put pen to paper I couldn’t stop. I wrote a piece about my Granny Amy who was a very strong Romany woman. She was a flower seller and walked for miles. I lived with her and my Grandfather for a number of years and remember her bringing the flowers into the hallway, the scent strong, pungent, filling the house as if it were one huge flowering vessel.

‘Spanish dancers,

blood orange dahlias

soaking in water.’

(From Up Early)

As I wrote I was aware of a flurry of memories.

‘It’s 1963, I’m seven years old./ My sister and I are sitting on the floor gnawing on pig’s trotters./ The fire crackles and spits./ Coronation Street is on the dikkamengro./ Granny’s going on about Annie Walker’s hair style and Bet’s low cut blouse.’

(From Pig’s Trotters, Coronation Street and a Noisy House.)

Within a few months I had written over thirty poems and monologues. By re-connecting with my ancestors and speaking with relatives I uncovered a rich treasure of stories, beliefs, all manner of things. I plucked memories from thin air and dug deep into the earth to find buried secrets. I came across objects and belongings, like my Mother’s gold hoops and sovereign (balanzer), Gypsy pegs, (faidas), old peg knives, (churi’s), and I heard about the talking stick, (o pookering kosh), used to perform a ritual for the dead. This I didn’t find but a close friend carved one using a branch from the blackthorn bush. I set up an altar and placed family photographs on it. Sometimes I would pick up a photograph of someone, study it, then speak with that person, ask him or her questions, make notes, a sort of stream of consciousness writing. If I didn’t have a photo I would re-imagine what they looked like, how they spoke, how they dressed, what sort of habits they may have had. One such person was my Great Aunt Tilda whom I had heard stories about.

‘me great aunt tilda, now there was a character, a funny old malt, she was me dad’s aunt on the lane side of the family. she always wore men’s clothes, dark coloured trousers, shirts, waistcoats, a black stadi with a gold ‘at pin on the side and a little purple feather.’

(From Great Aunt Tilda, A Funny Old Malt).

Another character that I didn’t know but heard so much about was my Great Grandfather, John Ripley. He came through to me loud and strong. I heard how he was born under a gooseberry bush. I pictured him being born and the family fussing over him.

‘I was named John Ripley, after me dad. The ‘ead rom came down and blessed me, he tied a little bag of rowan berries round me neck to ward off the bad mulo and to bring kushti bokt.’

(From Under a Gooseberry Bush)

Writing about my ancestors has been a way for me to re-connect with them. When I read my work at poetry events I am filled with a surge of energy that I haven’t experienced in a long time. Even if I am feeling exhausted or unwell prior to the event, as soon as I begin reading I come alive. In honouring my ancestors I have been gifted with renewed optimism and hope. I wear my Mother’s gold hoops and I remember my Great Aunt Ria showing me her gold, a symbol of prosperity and wisdom.

‘sovereigns and gold chains/ hanging from her neck/ rings through ears on fingers/ at night/ she places them in an embroidered bag/ slips it under the mattress/ she sleeps soundly/ as the gold warms itself/ longing for her soft skin/ and light.’

(From Aunt Ria’s Gypsy Gold)

Romani words (jib) – Dikkamengro – television (looking box); Malt – woman; Stadi – trilby hat; Rom – Head of the Gypsy Tribe; Mulo – spells; Ksuhti bokt – good luck.

Poems published in ‘Apple Water: Povel Panni’ and ‘they lit fires: lenti hatch o yog’ with Hedgehog Poetry Press.

Raine Geoghegan, M.A. is a poet, prose writer and playwright of Romany, Welsh and Irish descent. Nominated for the Forward Prize, Best of the Net & The Pushcart Prize, her work has been published online and in print with Poetry Ireland Review; Travellers’ Times; Ofi Press; Under the Radar; Fly on the Wall; Poethead and many more. Her pamphlet, ‘Apple Water: Povel Panni’, was launched in December 2018 and was listed as a Poetry Book Society Spring 2019 Selection. ‘They Lit Fires: Lenti Hatch O Yog’ was published in December 2019, with Hedgehog Poetry Press. Her first Full Collection, ‘The Talking stick: O Pookering Kosh’ will be published with Salmon Poetry Press in March 2022. Twitter @RaineGeoghegan5

(All images reproduced by kind permission of the author)

Text & Images by Stefanie Rixecker

Akaroa, New Zealand

January 2021

For some, familiarity breeds contempt. For others, it yields appreciation, connection. I am in the latter camp, perhaps because the first twenty-six years of life involved 30 moves across three countries, three continents. I loved being peripatetic, discovering new places, new people. At some point, though, a longing for “home” surfaces, even if home is no longer a place of birth, or ancestral connection.

Although I still have fond memories of northern hemisphere January - a month of beginnings, setting goals, planning the year, playing in the snow – I also remember it as a time of reflection, awaiting the release from winter’s darkness and the promise of a warmer sun. So, these past twenty-seven southern hemisphere Januaries offer quite a contrast. Here, it’s a month of abundance when summer’s bounty unfolds in the splendour of berries, stone fruit and homegrown veggies. It’s a month filled with sea spray, long, hot days at the beach or on the water, and cool evenings listening to the sea lap the jetty. It’s a month of roses and geraniums alongside the bright hues of summer natives, notably pohutakawa and southern rata in resplendent reds. “It’s summer!”, they shout.

The month is filled with fun, friends & family, boardgames and swim races alongside long, languid lunches of homemade fare. Some days bring calm early mornings, perfect for a solo kayak on the harbour. With summer comes the joy of reproduction – fledgling native birds, seal pups alongside precious Hector’s dolphin calves. Soon, too, the treat of Orca bringing their young into the harbour to hunt stingray and dazzle the locals. These are southern hemisphere rhythms in Akaroa, Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Akaroa has been in my life for the past twenty-seven years, since I first set foot upon Aotearoa, land of the long white cloud. For many years, I visited annually and had the privilege of sharing a family bach (humble holiday house) for sporadic, yet always significant visits. These past five years have seen an even greater connection through building my own hut and bach, places for reflection, connection and writing; weaving place and word, crafting natural and cultural history.

During this same period, I wove strands of life together – an academic career, a precious family, relationships in and with the people of this place, an understanding of the layers of history that continue to shape this land and its people. Throughout this time, half my lifetime now spent in one place, Akaroa got under my skin. It is more than a singular place or site. Indeed, it is better expressed in Te Reo Maori (the language of the indigenous people, Maori) as tūrangawaewae – a place to stand; a place of particular empowerment & connection; my foundation; my place in the world. In short, my home.

I now visit most weekends throughout the year, and in January I stay for weeks on summer holiday. This month feels like a portal to another world, time in suspended animation, one day bleeding into the next. The blissful feel of “summer holiday” is here, rain or shine, even with the weekly visits throughout the year. January is a special time, familiar and fleeting all at once.

The village of 700 permanent residents swells to upwards of 1500 with holiday makers and bach owners settling in for the summer. And still I take the same walks through the local cemeteries: Anglican, Roman Catholic and Dissenters. The names on the tombstones are the same, familiar characters of another era occupying the present, connecting history. How can one grow tired of these familiar souls who walked these hills, swam this harbour, shared this space?

Nor do I find contempt on the familiar pathways through the Garden of Tane, a now scenic reserve covering hectares, originally created in 1874 when the Canterbury Provincial Council set aside 5 acres. It includes many exotic species, some planted to commemorate the great peace after World War I and again World War II. The 1960s saw this space grow and cared for by a farmer and environmentalist who re-introduced native plants. It fell into disrepair upon his death and only in the early 2010s has it again been re-invigorated by locals. I’ve walked these paths for twenty-seven years, across planting trends and stages of neglect and newly found love. No matter when, these paths call for another visit.

Here, it’s easy to find cheeky pīwakawaka (fantails, Rhipidura fuliginosa) hopping from branch to branch, twittering a cheerful tale. And within seconds the calls of the korimako (bellbird, Anthornis melanura) chiming in unison celebrating their continued return. The whirring of feathers, perfectly timed through tight branches, can only be their feathered signature. This feathered whirr contrasts with the deep thrum of the kereru (wood pigeon, Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae), working to keep its svelte, curvaceous body in the air. More recently, this walk also includes tui (Parson Bird, Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae), their clicks and calls adding to the korimako increasing holiday chime. These birds had all but disappeared – indeed, tui weren’t here when I first visited in 1993, and korimako were quite rare. Thanks to human intervention – predator trapping and tui re-introduction to the Peninsula – the dawn silence has turned into a dawn chorus of native birds declaring their return. No contempt here, either!

Akaroa Harbour is the result of volcanic activity between 11 and 6 million years ago, leaving two overlapping volcanic cones. The valleys were flooded as sea levels rose approximately 6000 years ago, connecting land to the Pacific Ocean. More recently, Akaroa was noted in the “top 5” destinations in the world for cruise ship holidays. Since March 2020, it’s been quiet, though, with all cruise ships banned as Aoteroa closed its borders due to the global pandemic, COVID-19. This has removed all international tourism, with no tenders running to and fro while the ships are anchored, creating a much quieter harbour with significantly reduced traffic for humans and wildlife alike.

This year has seen a success in breeding for the endangered Hectors’ dolphins (Cephalorhyncus hectori), the world’s smallest dolphins endemic to these waters. To date, six mothers with calves have been spotted - four more than last year with the potential for more yet to come. Indeed, later this month, I’ll be onboard a research vessel to spot marine mammals and assess water quality. No contempt in these familiar moments either. Rather, recognising the importance of routine, data and monitoring connects the familiar with the dissonant, thereby pointing to change and action.

It’s in seeing the every-day, the familiar, that we can also notice differences – improvements and setbacks. These help map our place, the places and spaces we share with wildlife. Being connected, understanding, expecting the familiar, all help us to see patterns and set expectations. If and when these familiar patterns change, they can give us hope – like the continued naturalisation of tui on the Peninsula – or raise concerns - like the 2nd year of blue penguin deaths due to low food supplies in December. Understanding the familiar and appreciating it means connecting with changes and determining when and how interventions can benefit.

And so, I reflect on twenty-seven years in one place, not my natural home, yet now my naturalised home. Becoming of a place requires time, focus, connection – a commitment to place, the familiar. While I now call Akaroa my home, my place to stand, I also know that I am still becoming a naturalist in residence.

Stefanie Rixecker was born in Germany and has lived in four countries and on three continents. After attaining her doctorate in the US, she worked in academia in environmental policy & management for 25 years, attaining a full Professorship alongside publishing numerous journal articles and book chapters on environmental issues, including climate change and environmental justice. She’s a sought after public speaker, having delivered over 100 addresses worldwide. More recently, Stefanie actively moved from theory to practise, and now leads the largest regional government organisation in Aotearoa - which has responsibility for environmental management of freshwater, biodiversity, natural hazards and climate change impacts, amongst other key areas. Her current passion is learning to bridge academic prose with nature writing; her photos and favourite quotes can be found at her Twitter site @SRixecker.

A (not always) monthly free newsletter full of wild woman wisdom, ways, and wonderings

WILD WOMEN PRESS

CONTACTS

Email: vik@wildwomenpress.com