Thread 62 - A Voice Can Sound Like Silence - Caro Giles

Thread 61 - On Winter Resilience for Elastic Writers - Polly Atkin

Thread 60 - Creative Adventures (at 70+) - Wendy Constance

Thread 59 - Wild Menopause - Gill Hands

Thread 58 - When the Going Gets Tough - Dr Liz O'Riordan

Thread 57 - On Tending the Magic - Sarah Thomas

Thread 56 - Bone Woman - Isla Macleod

Thread 55 - Finding My Voice at 50 - Maya Jordan

Thread 54 - Write it LOUD (or if in Scotland, Gie it Laldy) - Catherine Simpson

Thread 53 - Wild Brown Women - by Aman, Harleen, Mehwish, Sati & Simran

Thread 52 - A Net To Catch Time - Samantha Clark

By Caro Giles

December 2023

Northumberland, UK

The storms this year are shifting the sand more violently than the year before. It is the middle of November and my daughters and I seem to spend longer than necessary talking about whether or not it is cold enough to wear gloves. In a couple of weeks it will be as if these conversations never happened, and our breath will hang in the air when we step outside.

Today it is Saturday, and thousands of people are marching through London because they want to live in a world that is not defined by conflict. I want to march with them, but we live over three hundred miles north of the capital in coastal Northumberland, and noisy crowds overwhelm my children. Today we craft our own gentle rebellion

We spend an hour cutting paper into shapes that we stick onto jars, then we place candles inside the jars and watch the flames flicker. The littlest one cuts out blue letters spelling

P E A C E and when she tries to glue them on they peel off the glass curves. With care we manage to fasten them so they stay firm: she is determined that her message of P E A C E will hold fast. When the girls were tinier I wrapped this daughter up in a sling and popped the middle two in a double buggy while the oldest one held onto the handle, and we marched together. An onlooker once shouted at me, demanded to know why I was bringing my children out to a protest. When something like this happens it feels like another attempt to erase me.

Our nearest beach is at Alnmouth, a small village that is viewed from the nearby mainline railway as coloured houses stacked in rows around an estuary pouring into the North Sea. Today I tempt the girls with a visit to the post office, with its walls lined with jars of cola bottles and jelly babies, but my mind is full of a violence that contrasts sharply with sweets being poured into scales. Alnmouth was ripped in two during a storm on Christmas Day in 1806, slicing through the oxbow meander and cutting off Church Hill from the village. Sometimes, at low tide, my daughters and I walk over marram draped with seaweed to the top of the hill. A cross marks the spot where St Cuthbert supposedly agreed to become Bishop of Lindisfarne. Once we nearly got caught by the incoming tide and drove away up the lane as waves licked the tyres.

On this Saturday, as we walk on the beach, my daughters and I examine the evidence of the storm that slammed into Alnmouth a couple of weeks ago. It sliced into the dunes that fringe the beach, leaving jagged wounds that bleed out sand. The wooden walkway that leads down from the village now ends abruptly almost a metre above the beach, which is still strewn with seaweed tangled into knots. It is nearly high tide, and the shoreline is edging closer, seeping into the bladderwrack. My daughters quickly shed their coats and jump onto concrete blocks that are now fully exposed all along this section of the beach, evidence of another conflict, planted there in anticipation of an enemy that never reached our shores eighty years ago. We have learned nothing, I think.

Then the child who was born before her caul could rip open and release her into this world looks at me with eyes the colour of hope. She carefully unties her walking boots and peels her legs out of her trousers. I take them from her and glance along the beach at her little sister, who is walking away from me into the afternoon. I turn back to the shoreline, where my daughter gasps as bubbles run over her toes. It is so cold she whispers. And I breathe in her words, because there have been times when she is completely silent: mute months that hurt my heart. She leans into me, gripping pebbles with her bare feet, and we call to her little sister.

Caro Giles is a writer based in Northumberland. Her words are inspired by her local landscape: the wide empty beaches and the Cheviot Hills. She writes honestly about what it means to be a woman, a mother and a carer and about the value in taking the road less travelled. Her writing has appeared in journals, press and periodicals and she was named BBC Countryfile's New Nature Writer of the Year in 2021. She writes a regular column for Psychologies magazine and her debut book, 'Twelve Moons', was published by HarperNorth earlier this year. She can be found on Substack and on Instagram @carogileswrites.

By Polly Atkin

October 2023

Cumbria, UK

Every autumn the old fear comes. Wordless and looming at leaf-fall. How will I cope through the coming winter? How bad will it get?

Every year I try to calm the terror with the same rational planning. I tell myself I will make use of the dark hours. I will be very productive. I will sit by the fire and read and write and carve something out of the cold. I will be gentle on myself, because the winter will not be gentle on me. But I will turn it to good. I will use the enforced slowness of winter well.

Instead, I shiver and sulk. In pain and cross about it. Unable to scrabble up out of the frozen fog of my thought-mulch to see where I am and where I want to get to. Pinned down by my own heavy limbs. The best I can hope for is it sit it out.

I can’t remember a time I didn’t meet autumn with dread. Even in childhood it was like this. In the summer I was solar-powered. But in the autumn term I would sicken – with something, everything. I would get tireder and tireder as the year slid towards its close, grey-faced and black-eyed. I was like two creatures, shapeshifting at equinox.

Probably I am exaggerating, and it was not always so clear cut. But by my teens I had come to associate autumn with sickness, with rocketing pain and fatigue.

It’s not that I hate winter, I say to people, but that it hates me. But that’s not true is it? I am irrelevant to it, but I cannot ignore its relevance to me – the particular susceptibility of my peculiar body to shifts in the seasons and weather.

It doesn’t matter how much I love elements of autumn and winter – the light through the turning leaves, mist in the morning, the secret ministry of frost, transformational snow – I know it will hurt me.

I’m old enough now to not expect this to change. But I’m also old enough that I should be able to learn from experience and not repeat past mistakes.

For regulars in the monthly poetry reading group I facilitate, my moribund dread of autumn is a long-running joke. Our reading is seasonal, and each year as winter approaches, I waver towards the maudlin. In October 2019 though we read John McCullough’s beautiful poem ‘Spout’ and developed a Winter Resilience Plan together, centred on the yellow teapot of the poem as a kind of domesticated sun. The following year we talked of storing up summer like the meteor jam in Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s ‘Summer Haibun’, to spread on the ‘still-warm bread [of] winter.’

Like many people, I find the word ‘resilience’ troubled. It has been co-opted to place responsibility on the individual to counter adversity, whilst ignoring systemic pressures. But I’ve been thinking again about the word’s root in elasticity, in flexibility. I’ve been thinking about what a Winter Resilience Plan might look like that is about more than just holding on, although holding on is sometimes the most we can do. I’ve been thinking about adaptations. I’ve been thinking about becoming my own heat source, about whether we can make our own light, not just can it for later.

These pandemic years have made the coming of winter even harder. Like millions of disabled and chronically ill people, I know I can’t be casual about the risks a covid infection poses to my precarious health. Winter brings both fewer opportunities to socialise outdoors in relative safety, and rising infection numbers, making everything more dangerous, from essential healthcare to spending time with friends and family. All the things that used to lighten the physical toll of the colder months for me – Halloween parties, sparkly Christmas and New Year gatherings, cosy pubs, transporting gigs, evenings at the cinema – are inaccessible to me now. Though I know how lucky I was to be able to enjoy them whilst I could.

But there are compensations. My life may be quieter now in many ways, but it is full of riches – the gold of midwinter sun shining through mist rising from the lake; the splendid velvet of roebuck antlers. I want to celebrate those riches, and to recognise the privilege it is to be able to enjoy them.

Some of Us Just Fall begins and ends with autumn. At the end I am trying to recalibrate how I feel about autumn, ‘to think of this as the beginning of something … a kind of understanding, or a promise of understanding to come.’ I give myself permission to ‘sleep for four months in the dark of the cave house’ and I hope, in giving that permission to pause, I will be able to resume.

Polly Atkin (FRSL) lives in the English Lake District. Her publications include poetry collections Basic Nest Architecture (Seren: 2017) and Much With Body (Seren, 2021), biography Recovering Dorothy: The Hidden Life of Dorothy Wordsworth (Saraband: 2021), and a memoir, Some Of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better (Sceptre: 2023). She has an essay on rain and chronic illness in Moving Mountains: Writing Nature through Illness and Disability (Footnote: 2023).

By Wendy Constance

September 2023

Essex, UK

Where to start unravelling my thread? Labelled as “reserved” in 1960s school reports, too shy to work in the creative industry, I was bundled into business studies rather than the art foundation course I coveted. A lifetime of office work loomed - curtailed by embracing opportunities to study as a mature student every couple of decades that ended up leading to a career designing household textiles, followed by teaching arts/crafts in Further Education. Writing ascended in my fifties. My children’s novel Brave published in 2014 after winning a competition.

By then I ‘d moved back to the Essex coast, after 34 years in West Yorkshire. Content to live on my own, with close canine companionship and a long-distance human relationship. An enduring interest in the natural world blossomed during long beach walks with my dog Lola, alongside growing despair at the amount of plastic litter. Wacky woman that I am, I washed and sorted the growing collection of plastic beach litter, potential use for art.

A one-year journal of the walks became the foundation for my Wild Writing MA dissertation. Studying nature and the environment, researching local social and natural history, broadening my reading, whilst developing my writing. I started leading eco-writing workshops, for children and adults 5 years ago, for Essex Book Festival.

A bit of a butterfly, I’ve tended to flit from project to project, prose to poetry, writing to art, resulting in unfinished WIPs (Works In Progress). Most of my work concerns the natural world/environmental issues. And I’ve started experimenting with combinations, creating artworks with a message about the plight of nature, some exhibited locally.

And so, what next?

Listening to, and acting upon your intuition is what I should have heeded more often in my seventy years. My instinct now is to further exploit my predilection for flitting between creative mediums; to focus on developing ideas generated by incorporating text within painted or textile art, be it embroidered warning or eco-poem within collaged painting; to share my passion for our planet, as I learn more about trees and fungi sharing information, seagrass’s carbon storage, plastic in melting glaciers. And I'll keep hoping to engage and inspire the viewer/reader/those in power; hoping that more people start caring about what’s happening on Mother Earth. Without hope, and without care, the harm will continue.

This lone butterfly is ready to join a wolf pack - though not a seeker of the limelight, more of an introverted wolf who wants to raise others’ voices. Maybe it’s time to howl, if being a quiet craftivist and wannabe activist is having little impact. Or maybe the art-forms can do the howling themselves, make an impression, given the right platform.

Time to develop my social media skills …

Wendy Constance gained a BSc Textile Design and Design Management in her mid-twenties; MSc Textile Design Technology in her mid-forties; MA Wild Writing: Literature and the Environment in her mid-sixties. Winner of 2013 Times/Chicken House Children’s Fiction Award, her children’s novel Brave published 2014. Other publications include: The Unheard, eco-essay Creel 4 Anthology, 2018; A Good Place to be Alone, haibun, Fenland Poetry Journal, Autumn 2022. She edited the booklet, Tides of Tendring.

Her growing concern for the plight of the planet led her to join volunteers working on a project for Jaywick Martello Tower about the past, present and future risk of coastal flooding. Since 2019 Wendy has been involved in various events for Essex Book Festival, from making hundreds of origami peace doves to leading prose and poetry writing workshops for adults and children, with environmental themes. In 2023 this included a series of eco-poetry workshops at local primary schools inspired by The Great Flood, it being the 70 year anniversary.

In 2021 she received Arts Council DYCP funding for developing the creative practice of writing eco-poetry. Wendy is currently working with a group of artists and writers on a project called Turbulent Flow, funded by the Arts Council, on the topic of offshore wind power.

Twitter/X - @WendyConstance. Instagram – creative.wendyc

By Gill Hands

August 2023

Cumbria, UK

Around twenty years ago, menopause and perimenopause weren’t on the media radar like they are today. When I started the long journey, I consulted with friends who were ahead of me, then ratched around on the internet for information. Amongst the hot flushes and sweats (tip: I stuck my legs out from under the duvet), the NHS website listed a whole host of other symptoms. The online world seemed to be unrelentingly negative, and though I had a few physical and emotional symptoms that sometimes made life difficult, I found a new creative energy that I couldn’t find mentioned anywhere.

Difficulty sleeping

Insomnia became my friend. I joined the 3 AM club. My mind was incredibly fertile and I was in tune with my unconscious more easily when everyone else was asleep. I dreamed vividly and used the images and metaphors in my creative work. My random, repetitive, revolving thoughts became rhythms and rhymes. Sleep deprivation induced an altered state of consciousness that was almost magical, dreams and reality merged together and became poetry and art. Where there black hooded things on the landing? It didn’t really matter they became part of my art. I explored my own psyche and sexuality, examined ideas of quantum psychics, memory, and the meaning of life, (amongst other things) all from the comfort of my own bed. It was amazing, frustrating, tiring and exhilarating all at once, and became the inspiration for my poetry collection Rilke Tattoo (Wild Women Press 2006)

Vaginal dryness/discomfort during sex/reduced sex drive

My experience was completely the opposite. To put it bluntly, I was dripping with horn. I’m still unsure if this was a problem or not but it doesn't seem to get mentioned much. I went into overdrive in my body’s last ditch attempt to get pregnant. At first, I was desperate to have another baby, but fortunately my logical brain intervened and I wrote poetry instead. My increased horniness let to marital disharmony and a brief affair. Although short in action, this led to a long correspondence on sexual fetish, gender roles, obsession, and unrequited love, which culminated in my first poetry collection Internet Love Slut (Wild Women Press 2004). I learned more about myself than I wanted to know, and it wasn’t easy because I was brutally honest in my work, but I survived and our marriage survived.

Problems with memory and concentration

I didn’t have a problem with remembering, but with forgetting. Too many memories crowded into my head, wanting to be understood and written down. Of course, these were filtered through my own unreliable narrator, but what is reality anyway? This fuelled the insomniac thoughts and the search for scientific and spiritual understanding. My concentration on my work was fierce, but mundane tasks could be conveniently forgotten about. ‘Her head is somewhere else/certainly it is not on the cheese and cucumber sandwiches/she is dutifully making.’ ( The POET is angry with the cucumber, Rilke Tattoo; Wild Women Press 2006) I was in touch with the real world of the soul and not the everyday.

Low mood or anxiety

If I hadn’t been able to create, I am sure I would have had low mood, but I wrote morning pages everyday, encouraged by The Artist’s Way (Julia Cameron) and Wild Mind (Natalie Goldberg). I wrote down my dreams, and drew or painted some of the symbols. I came to a deeper understanding of myself. I began to perform poetry and connected with other amazing poets. I went on a performance course at my local college, where I was older than everyone else including the tutors, but I learned a lot and went on to perform my poetry across the UK, turning up wearing a nightie at Sheffield Literary Festival and fairy wings with wellies in the spoken word tent at Glastonbury. I was sometimes down, and sometimes anxious but I had the friendship of my creative family of Wild Women and the wider network of poets, writers and artists I met along the way.

Over time the need to write, perform and make art slowed down as I came through the other side of menopause and reached a deeper understanding of my own psyche through art. The insomnia became intermittent because I didn’t need it any more. As I wrote in my poem Peter Pan ‘...there was no need to chase my shadow,/step on it; search for it in someone else./I scooped it from the dark,/swallowed it and slept.’ (The 3am Club anthology, Wild Women Press 2006.)

Creativity helped me through the menopause, and the menopause inspired my creativity. It wasn’t always easy, but it was an amazing time and I wouldn’t change anything. Not everyone has the chance (or the inclination) to make art and exhibit it, take a performance course, write poetry, novels and perform at Glastonbury but everybody has something to express.

If you try and dampen down those inner voices that make you question your life, if you try to gloss over the major life change that is occurring to your body, if you try to fit into a world that doesn’t fit you any more, then you will shrivel. Menopause isn't all negative. It’s a time to look at yourself, look hard, look deep, and be creative.

And remember, as Clarissa Pinkola Estés says, in Women Who Run With the Wolves

'If you have yet to be called an incorrigible, defiant woman, don't worry, there is still time.'

Gill Hands is a Wild Woman and founder-member of Wild Women Press. A writer, poet and artist, she has published work on Marx and Darwin (Hodder), her poetry has appeared in several Wild Women Press anthologies, and she has published two collections, Internet Love Slut, and Rilke Tattoo. As well as painting, writing and performing her way through menopause, she also took up drumming and bought herself a shiny green drumkit to bang. She lives in West Cumbria, where she continues to tend the wild things that grow.

By Dr Liz O'Riordan

July 2023

Suffolk, UK

I never thought of myself as a proper writer. I hated creative writing at school. It felt like my imagination was locked in a box. Give me something to research and I’d be happy, but ask me to write a story about a rabbit on a train and I’d be permanently stuck.

At medical school I was introduced to the art of writing scientific papers, and during my PhD I learned to craft sentences that were longer than most normal paragraphs. The art of reading 500 papers and turning all that knowledge into a chapter was something I relished.

I did keep a diary at school but it was mostly 2-3 lines at a time about the extremes of my life – being bullied, how to talk to boys and wondering when my boobs would grow. I didn’t keep them. My personal life remained behind lock and key and remained that way into medical school and beyond.

My world was turned upside down when I was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 40. I was fit, had no family history and ironically was working as a consultant breast surgeon at the time. This time I didn’t keep it a secret. I was being treated in a hospital where I had worked as a junior doctor so was bound to be recognised as I went to my appointments and I didn’t want anyone talking about me behind my back. The day after my diagnosis, I told Twitter and suddenly patients were sharing their tips to help me cope with what was to come.

In the throes of chemotherapy, my husband suggested I start a blog. It was 2015 and he said they were all the rage. The next day, he’d knocked up a website and I started posting updates about my treatment though the eyes of a doctor. I was still in denial and writing was a way to get my head around everything that was happening to me. The blog led to me writing ‘The Complete Guide to Breast Cancer’ – answers to all the questions being thrown at me by my new followers. I loved the fact-checking and updating my own knowledge.

And then lockdown hit. I’d had to retire as a surgeon due to side effects of breast cancer treatment, and despite sharing every detail of my breast cancer story, I had a burning desire to talk about a darker secret. One I was too scared to mention in public when I was working as a surgeon. I’d had severe depression for most of my life. Two close calls as a consultant where I thought about ending it. I had to get it down on paper. Writing it, reliving those painful memories had me in floods of tears, but I thought I was on to something.

I booked an online memoir course with the Arvon Foundation, where I met the wonderful Vik Bennett, along with other incredible women, and we continued to meet weekly, encouraging each other with our writing.

I filled notepads with memories of my life as a junior doctor, going through each job in turn. I wanted people I know how bloody hard it is to train to be a surgeon, especially as a woman when sexual harassment was rife. I needed patients to know what it takes to tell ten women a day they have breast cancer before going home to turn into a wife or a mother. I had to share the knowledge I’d gained on the other side of the operating table, but most of all, to show people that there was hope when the shit hit the fan. That it’s the little things that will pull you through (for me – it was volunteering at a hedgehog shelter and river swimming with a bunch of wild women).

I finished it in 2021 and my agent sent it to 5 different publishers who all said ‘No’. The market was saturated with medical memoirs, and they said it wouldn’t sell. I was told that I only had 2000 followers on Instagram and all I talked about was sewing and hedgehogs. I purposely did that. Twitter was my cancer space and Instagram was just for Liz. So after six months of hard graft and 12,000 followers we sent it off to another 5 publishers, who all said no.

I was distraught. I was this close to deleting everything, and then someone from Unbound sent me a DM on Twitter. They liked the pitch and I ended up crowdfunding it in 10 days – all thanks to the incredible people who follow me online.

And now my memoir – ‘Under The Knife – Life Lessons From The Operating Table’ – is finally out in the world. I keep having to pinch myself. I still don’t think I’m a proper writer, but if this book can help one person see their way through the darkness, then my work is done.

Dr Liz O'Riordan was diagnosed aged 40 with breast cancer whilst working as a consultant breast surgeon. Two years later she had a local recurrence and the side effects of treatment forced her to retire in 2019. She now talks all over the world about how to improve patient care. She wrote ‘The Complete Guide to Breast Cancer: How to Feel Empowered and Take Control’ to carry on helping patients. Her podcast, ‘Don’t Ignore The Elephant’, talks about the things no-one else does. Liz is also a keen sportswoman and is passionate about promoting the benefits of exercise for cancer patients. 'Under The Knife - Life Lessons From The Operating Table' (Unbound, July 2023) is her debut memoir.

(photo credit - Jenny Smith)

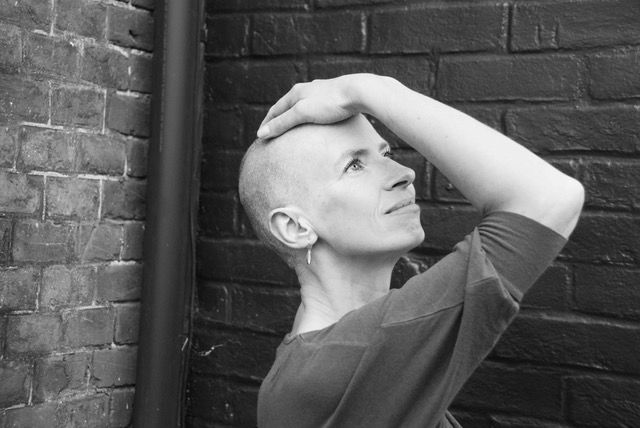

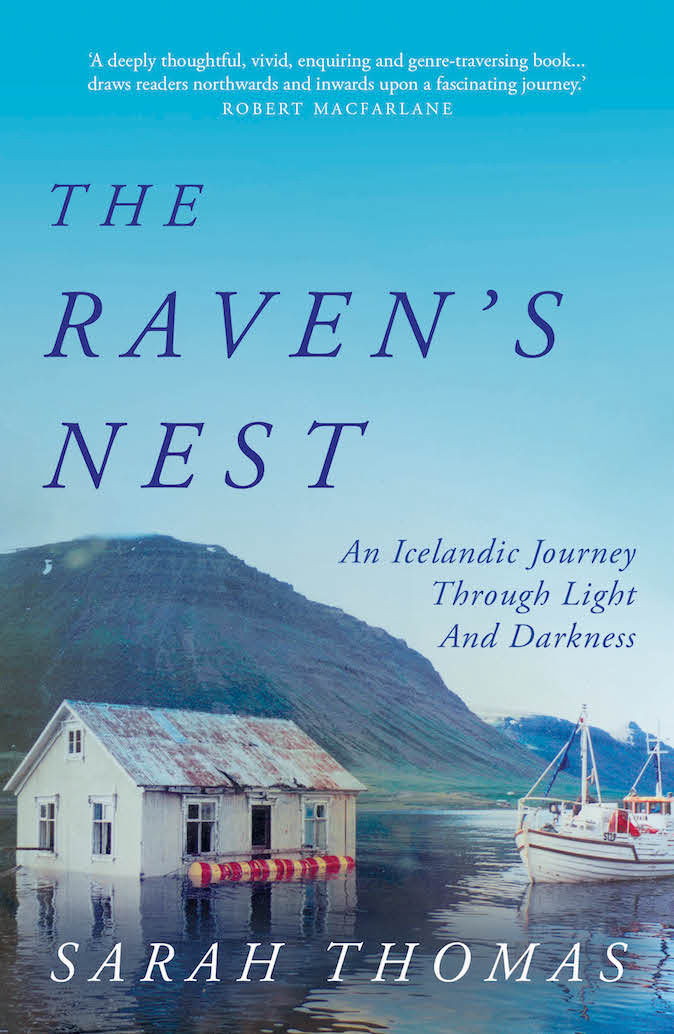

By Sarah Thomas

June 2023

Dumfries & Galloway, Scotland

Books are like magic: years of life and thought, colours, light, landscapes, voices, all pressed into a block of paper and ink small enough to slide into a bag or a pocket, which calls at you for company. When we read, we spend more dedicated time with a book than we would do with a partner. When else are we immersed, without distraction, in someone else’s voice and life for hours, days at a time? To be a writer, then, is an immense privilege. To be a writer is to weave magic. To be a writer sending her book into the world is to float a house on the sea.

Before there is a book there is writing - the long and shapeshifting verb. Sometimes it involves sitting at a desk; oftentimes not. In writing, a kind of magic also occurs. Over time, certain themes or objects call for your attention, quietly insistent. 'Coincidences' happen. Thought threads twine in ways that could not have been planned. Once, just once, I was gifted an entire chapter by holding two quartz pebbles from a special beach in Iceland - one in each hand. I had wanted to write about that thin place, where the improbable had happened, and the quartz gave me the way in. That chapter remained unedited and became part of a memoir, my debut - The Raven’s Nest: An Icelandic Journey Through Light and Darkness.

Next, the journey to publication and beyond involves navigating the opaque world of publishing with no map. Once, I might have naively assumed that there is ‘a way that it works’. Two years in, I can say that doesn’t seem to be the case. If there is a way, it is hard to find anyone who will tell you. It is a nebulous business with no direct link between cause and effect. That said, authors are under unprecedented pressure to do much of their own publicity - to be the mother and the midwife - but with little guidance. I have always thought of the magic I speak of above, as emerging from a dance between labour and grace. But if the labour feels relentless, or you are unsure what kind of labour you are supposed to be doing, I wonder sometimes whether it is more challenging for grace to visit.

This quandary has led me into conversations with other women memoirists about their experiences. Sadly for many, the process has been challenging at best and painful at worst. The clamour for a greater diversity of voices making their way to the page is slowly being answered by publishers. But the workings of the machine that brings them into the world are much slower to change: often not supple enough to accommodate what that diversity really means, or sensitive enough to the metabolism of struggle in the author's life that has had to occur for that book to exist.

Long before I found an agent, one writer's kind guidance - that the process of a book coming into being and finding its readers is definitively non-linear - has been a lodestar. So what has that looked like for me? What about the moss that grows in the shaded elbows of the machine, the light that slips past and over its whirring cogs?

My search for a literary agent coincided with the lockdowns of 2020. Everything, including the future of the publishing industry, was uncertain. It was frustrating to write proposal after proposal for a book I had already written, to hear nothing back and not know whether that was a 'no', or a 'not yet'. We were all having to be exceptionally patient with one another. At the same time, I was aware that really, there was only one thing I needed to be doing.

In late 2019, honouring the orality of my text and the Icelandic culture that had inspired it, and conscious that, for better or worse, eventually the book would become a 'product', I had made a commitment to read The Raven's Nest aloud to an audience from start to finish, so that it could exist first as breath on the wind, spoken. Inspired by the Icelandic tradition of kvöldvaka ('the evening wake'), where someone would read to the household while they spun, knitted and darned wool, by March 2020 I was mid-way through a series of candlelit readings, in a gallery in SW Scotland where I was artist-in-residence. I read aloud weekly to a roomful of people busy with their hands, or with their eyes closed, each being transported to another time and place.

All of a sudden, the pandemic was upon us and these gatherings were banned. I couldn't imagine creating that atmosphere, that togetherness, on Zoom. But as the months rolled on I knew I had to try. Together, we each lit a candle whose light filled those small squares on a screen. We could see one another's needles and thread – in, out, in, out. Somehow, the magic still worked.

The day after I finished reading it, I had a call from an agent; my agent. Three weeks later The Raven's Nest went to auction. The winning offer came in at the very moment I sailed into the harbour of the village in Iceland where the titular raven's nest lives. What strange convergence of life threads placed me there at precisely that moment? I don't know. But I do know that as writers, for all the labour, we must leave space for grace, for magic. To remain receptive to it and act in service of it. To let it play with our words in the world, carrying them to other realms of meaning.

In Iceland a year later, newly published book in hand, I made my way along a dusty track to a remote turf-roofed farmhouse to give a reading. Through bizarre coincidence, the audience that night was to be a group of Affect Theorists from across the world. I get a feeling for which chapter I will read when I am near or in the place I will read it. My instinct told me to read a chapter called 'The Whale' in which I dream of being in the sea with a humpback whale, and the dream is interpreted by a farmer. As I arrived at the farmhouse, a pod of humpbacks breached in the the fjord below, the evening light dazzling its surface. With their participation, the reading took on a new resonance.

I want to remain open to those moments, to the things we cannot plan.

Sarah Thomas has lived from the equator to the Arctic. She has a PhD in Interdisciplinary Studies. Longlisted for the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize and shortlisted for the 2021 Fitzcarraldo Essay Prize, her debut memoir The Raven's Nest (Atlantic Books 2022) won a 2023 Nautilus Book Award. She lives in Scotland.

Sarah Dyrafjordur - Photo credit N. Pilters

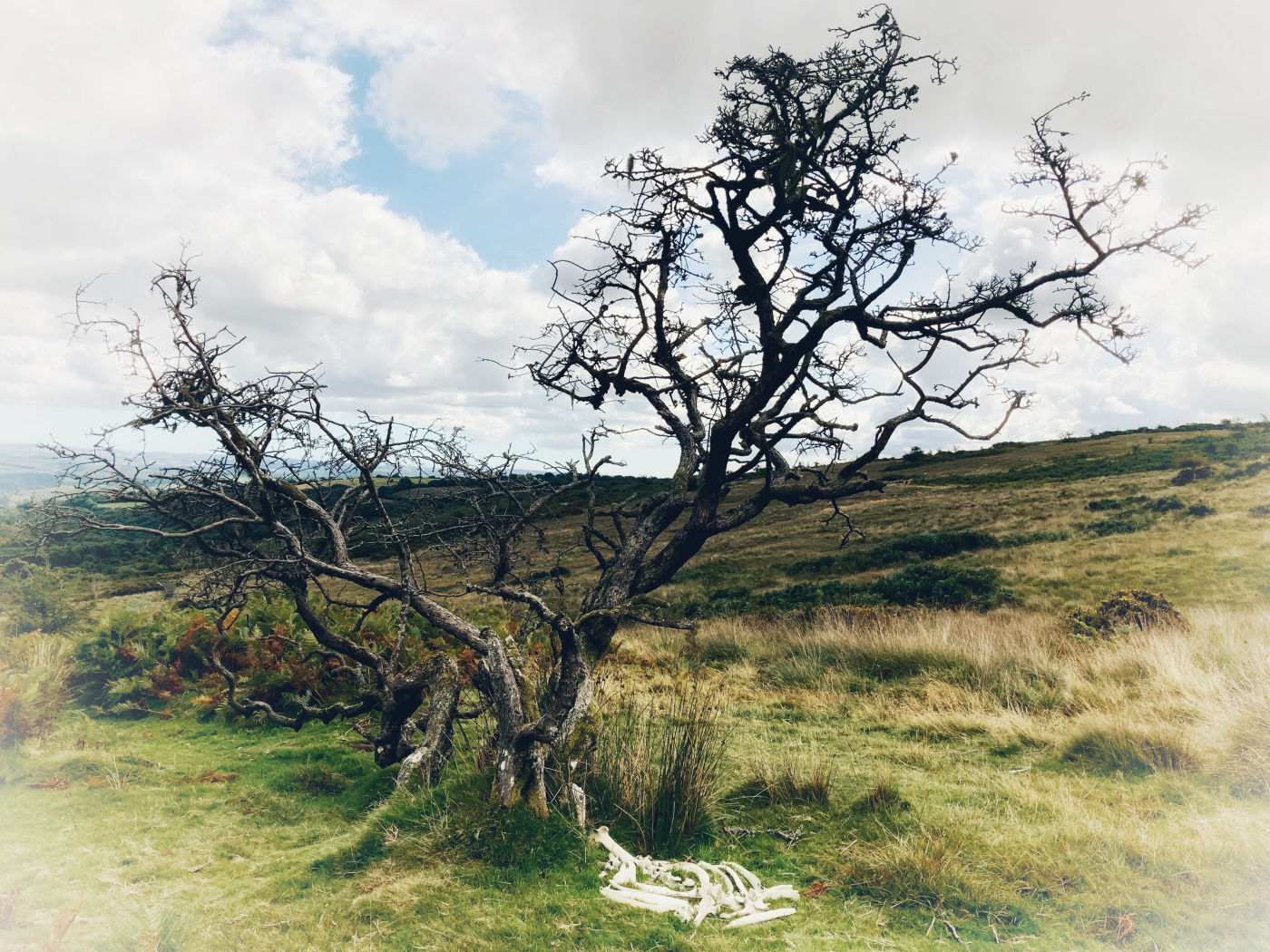

By Isla Macleod

May 2023

Somerset, UK

As the last rays of sun retreated from the wild moors, the twisted shadows of Bone Woman disappeared and I began to sing a soft lullaby to serenade the fading light and welcome the darkness of night. Barefoot, I stood and circled this dying Hawthorn tree whom I had come to love deeply.

She who has weathered the winds of change and called to me from afar, as I prayed for a wise grandmother to guide me across this threshold of initiation. She who stands rooted as Bone Woman, a midwife of death and rebirth, an elder of this land of rock, peat and bog.

Walking three times around her - bowing, clapping and singing as I praised her life and blessed her dying - I arrived at the shrine of bones I had gathered and formed into an offering upon her roots. I lay down the shawl from my shoulders and tenderly placed each bone upon it, before bundling them together as my voice and breath invoked their spirit to life.

With the bundle of bones held against my chest I stepped outside this Death Lodge and walked the short way to the babbling Snowdon Brook, alive with ancient voices as the waters tumbled over moss and rocks. Unwrapping the bones, my voice deepened as the grief stirred in my belly and the lullaby shifted into a soulful lament. I bathed each bone in the crystal-clear waters as the light faded and my heart filled with tears, softening my edges as I dissolved into the waters, becoming the hollow bones I washed, and the song of the stream claimed me.

For four days and nights I tended these bones, blessing them in the waters at dusk and dawn, and dreamt with them under the shifting sky, shimmering with silver stars. This vigil became a prayer to re-member, honour and praise the elders of this wild land of Dartmoor, Dumnonia, as I courted the Sacred and danced with my eros in devotion to Life.

The night before this quest I was preparing to sleep nearby in a beech grove when I saw the luminous moon rising, and felt the longing of my wild heart. It was Beltane Eve – the night when the Horned God gallops across the fertile earth, hunting for the Goddess to proclaim him Sovereign and Protector of the land as they commune in flesh and Spirit, restoring balance and fecundity to the earth.

On this night I felt the pull of the moon, the lunar-licked moors, and the feral call of the Stag King as I meandered through gorse and hawthorn, stalking him as he stalked me. I stopped and faced the pregnant moon as I listened for the sound of his hooves. As my heart quickened, I raised my drum and began to beat its skin, calling to my Beloved to rise up to meet me. My voice bellowed with ecstatic roars as I felt the fire in my heart stoked by his presence. I heard his hooves and felt his breath, warm and panting upon my cheeks. We made love again that night - his horns like swords, emanating from his crown, penetrating the night sky as I enveloped him and his seed was sown within me. I was enthroned as Wild Queen, guardian of our Sacred lands.

To celebrate this union and commitment to the land, on the final day of my vigil I opened the way for ceremony - rising to greet the dawn and tend the bones, before covering my naked skin in dark, thick, fertile peat from the blackest bog I could find and cleansing myself in the gushing waters. I bowed before Bone Woman as I unveiled myself and painted red ochre onto my limbs and face. Adorned in my finest robe, and crowned with a garland of ferns, ivy and hawthorn I prepared to marry my beloved Dartmoor.

As I walked up high above the sun-kissed boulders and singing stream, I gathered grasses, gorse branches, fluffy cotton stems and a crow feather to fashion into a wild bouquet as a skylark sang its sweet song overhead.

Arriving at a solitary hawthorn, presiding over these moors like a priestess, I knelt before her and wept as my heart cracked open with devotion to this place where I feel most at home, whole and holy. Under the white blossom, I wrote my vows and proclaimed them to the winds and winged-ones above: To love and protect these wild lands, to restore the Sacred and activate the ancient memory within.

With joy in my feet, I weaved my way back across the moors, stopping for a first dance with my Beloved, a congregation of sheep looking on, before returning to Bone Woman. I felt the quivering in her branches, like a twinkle in her eyes, as she blessed this union with her silent gaze. Her old bones a reminder of how to be forged in the furnace of your longing.

'Let the beauty you love, be what you do.' - Rumi

Isla Macleod is a ceremonialist, ritual designer and companion at thresholds. Dedicated to restoring the Sacred and inspiring a loving, reciprocal relationship with the natural world, Isla curates healing journeys and soul-crafting ceremonies and workshops that help activate pathways of remembrance and belonging.

Her book ‘Rituals for Life: a guide for creating meaningful rituals inspired by nature’ is a companion for those seeking to cultivate more connection, acceptance and wonder in their lives by honouring their natural transitions and thresholds

By Maya Jordan

April 2023

Mid Wales

I don’t know when I lost my voice. Loud and brash in my twenties I would stand my own with all comers, words dancing on my tongue full of futures and potential and bright sunny days.

Was it a life running after kids that quietened me? Certainly, four kept me busy. Then my mother-in-law died and, leaving two adopted kids with profound multiple disabilities, her two joined ours to make six. Six kids by the time I was 30, two requiring full 24-hour nursing care, is enough to silence anyone. But the words lingered, whispering in my ear, stories, half-formed, shimmering in the air.

Was it bereavement that stole my song? Or getting sick myself? Maybe it was the shame of not getting better? Was it the shifting of hormones or husband’s redundancy or the raising of teens, or the endless struggle with my weight? Or was it just being wrong? A loud woman in a world that wanted quiet. People like me don’t write.

I became quiet. I swallowed my words.

I see so many women reaching 50, realising that they have become quiet, have lived the last few years of their life with the sound turned down.

‘I used to be fearless,’ I hear them say.

‘I used to be brave,’ they whisper.

‘I used to sing.’

But the words would not remain silent, no matter how hard I tried to swallow them down. I wrote in secret, not sure why I had to hide. I told stories to my children and created worlds for their imaginations to roam, but that wasn’t real writing. Because people like me don’t write.

But the words persist.

In the early days, I called my words my musings, my mumblings, a bit of fluff, just messing about. Minimising my words and my voice like many of the women around me.

‘It’s just me,’ they say.

‘Going on,’ they mutter.

‘Take no notice'.

Why is this?

What happens to us?

Where do we go?

Now I call my words my conjuring’s, my magic, my powers. With the power to turn shapes on the page into stories, I find I have come back to myself.

We do come back, from wherever we have been. Finding our voices, practising croakily, we say our names, naming ourselves again in a new light.

No longer girls we are now the women of tall tales.

No longer girls, we clear our throats and if not roar – not yet at least – we can sing our name with pride.

There is a strength in this coming back to ourselves. Finding ourselves, our words, rediscovered amongst the debris of our lives.

Maybe that’s why we hear the words calling. Maybe that’s what we can hear, whispering at the back of our minds. Maybe this is not a calling back to who we were when we were young and loud and full of sound. Maybe this is a calling to who we are meant to be.

I found my voice at 50.

A Crone voice, growing stronger with age.

A voice that rings with truth.

A voice that rings with all the lives I have lived, all of the memories and all of the silence.

It is a voice that will be silent no more.

Maya Jordan is a working-class writer living in Mid-Wales. Having done everything from working as a cleaner to a community childminder, a children’s storyteller and a teacher, in 2019 Maya received a full grant from the Welsh Assembly to do a Masters in Creative Writing with The Open University.

She was selected for A Writing Chance - a programme supporting working-class and under-represented writers, with Michael Sheen and New Writing North, writing both fiction and creative non-fiction, as part of. As part of this programme, her fiction was performed by Michael Sheen in the BBC Radio Wales Margins to Mainstream.

Her work has been published online and in print, including in The New Statesman and BookBrunch. She has a fortnightly column in the Daily Mirror’s Lemon-Aid newsletter and has performed her work in The House of Commons.

A keen library user, she is passionate about access to creative arts for everyone, particularly disadvantaged communities and has taught creative writing as part of the Wales Wellness Program.

She writes a weekly blog at Bordering Grey – Writings on life while I go grey here on the Welsh borders.

As well as completing her first novel, Wild Women Gather, Maya is currently working on a screenplay and a memoir.

(Images by Maya Jordan - selection of personally special places in Wales - reproduced with kind permission )

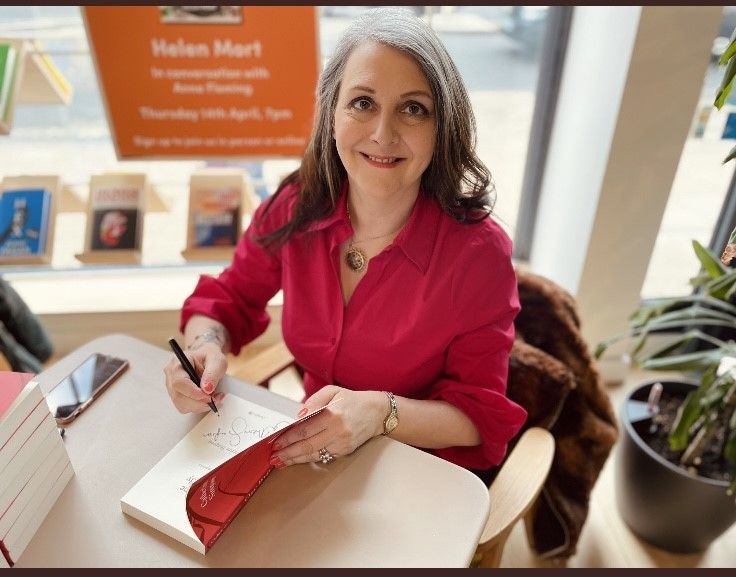

By Catherine Simpson

Edinburgh, Scotland

March 2023

I was brought up to be largely silent:

Speak when you are spoken to.

Stop being so giddy.

No laughing at the table.

Don’t interrupt!

Little pigs have big ears.

Children should be seen and not heard.

Stop mithering.

Hush!

Questions were not encouraged, and secrets never shared.

To be silent in these circumstances is to be ashamed. You do not have the words to explain or explore anything so feelings and experiences fester. There is no space for honest and open communication.

I was called ‘shy’ and I believed it.

‘Has the Cat got your tongue?’

When I was in my thirties I went to tap dancing lessons. We took part in the annual show which included sequins, silver-topped canes, gold waistcoats and whooping. I was quite happy about the sequins, the canes and the waistcoats but incapable of whooping. No sound would come out of my mouth. As I ‘step, ball, changed’ I was literally voice-less.

I mimed.

I later confessed to my fellow dancers that I had mimed my whoop, and they have never let me forget it.

So, the fact that this tongue-tied, ‘shy’ ‘cat got your tongue’ whoop-less woman became a memoirist, is a surprise.

I started writing as a journalist, telling the stories of others for first-person pieces in Woman’s Own and other magazines about broken hearts, broken marriages, broken bones, broken homes, miracle babies, miracle cures and miracle weight-loss. It was fascinating to interview people and write their stories without giving away anything about myself.

When I wrote my first novel, Truestory, I was forty-four and it was inspired by raising my autistic daughter, Nina. I would not have dreamed of writing about this issue in a memoir because it would have been too exposing – for me and for Nina. Nina was fourteen then, so I turned the autistic character into a boy to create some distance.

This only worked to an extent. My other daughter, Lara, said: It may be a novel, but Nina is on every page of that book.

But writing a story as ‘fiction’ gives you deniability.

Of course it is not based on truth…of course that never actually happened…

It is surprising though, how many people do not grasp the meaning of ‘fiction’ and assume that if something is in a book, it is ‘real’.

Them: What does your husband think of the way you have written about him?

Me: That is not my husband that is a made-up character.

Them: Yes, but what does he think?

With memoir there is no such deniability.

The contract with the reader is that if you call it memoir then what you write is true (or at least it is your truth).

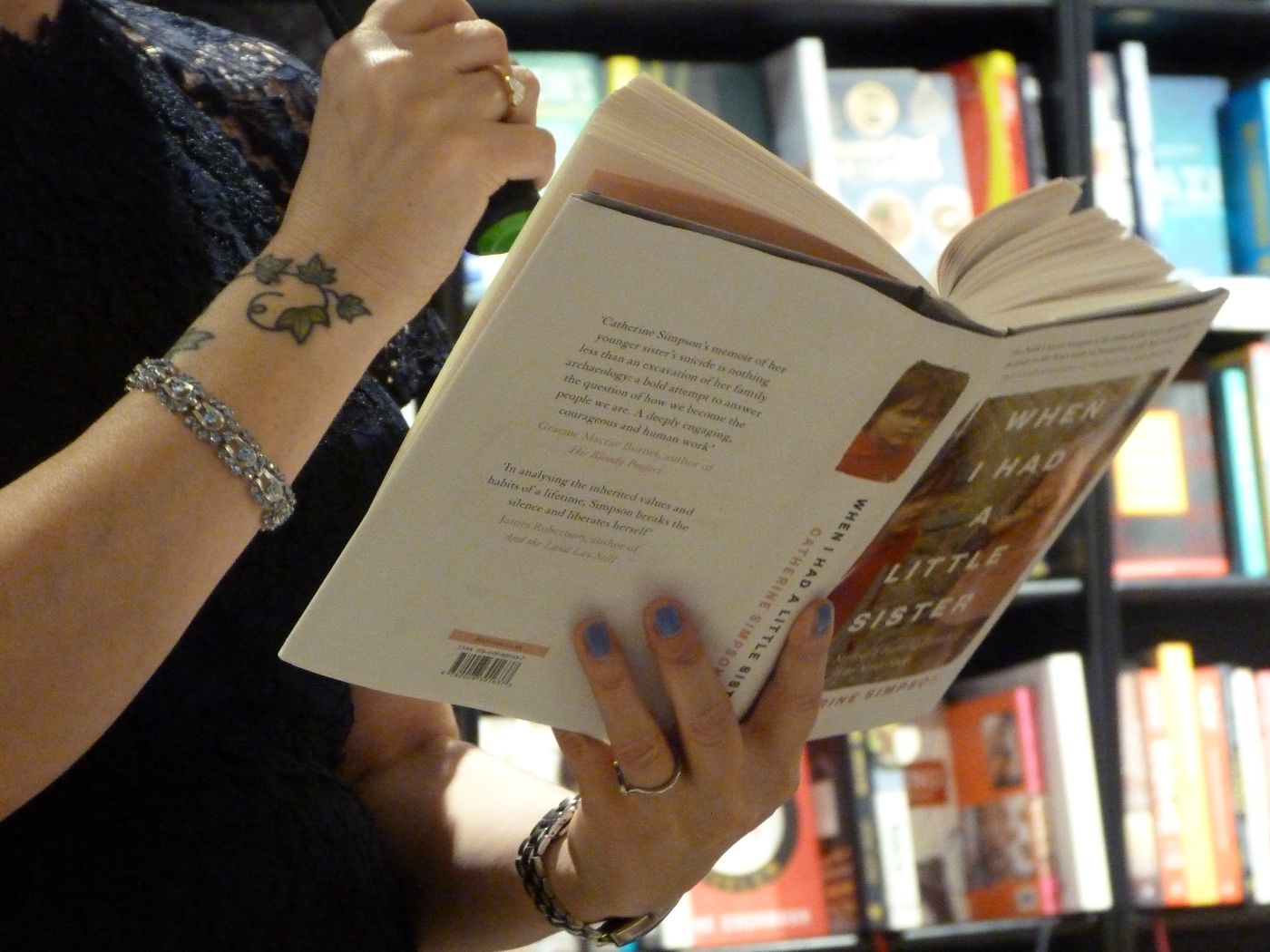

My first memoir, When I Had a Little Sister, was about the death by suicide of my sister, Tricia. I knew I was writing about other people besides myself – my father, my mother, my sisters. It was uncomfortable. I did not want to offend or upset anyone. I read somewhere that having a writer in the family is as bad as having a murderer in the family. No secret unrevealed, no stone unturned, no privacy remaining after all that dirty linen has been washed in public.

While writing the memoir I asked myself: Is it true, is it fair, is it important to the story. If it was all three, it went in.

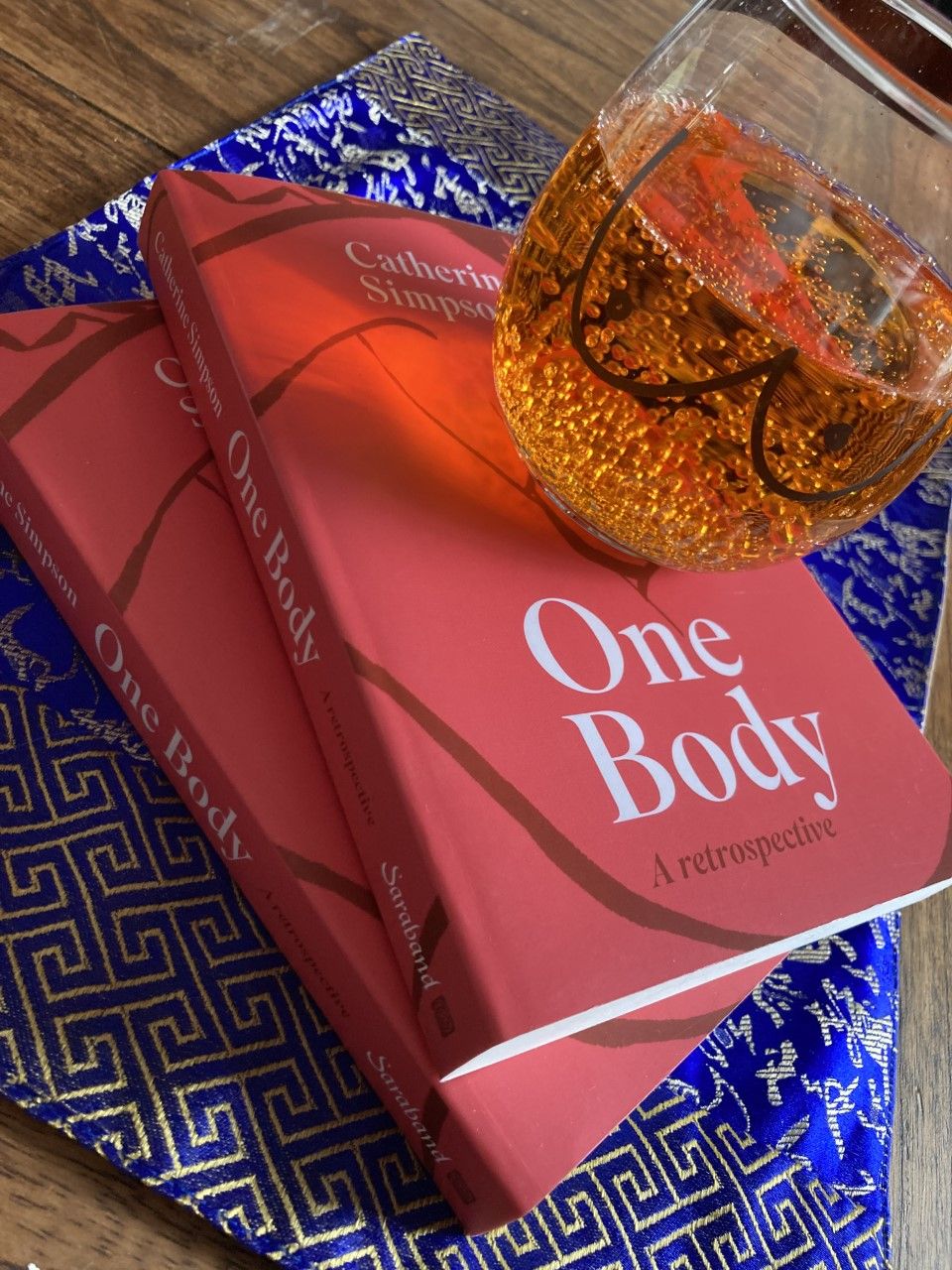

However, with my second memoir One Body – about growing up and growing older in a woman’s body and my experience with breast cancer – the writing felt freer. This was my story, about me, I could say what I wanted, and that feeling of freedom was heady.

There were taboo subjects to include in One Body – sexual assault, abortion – and I asked my husband and daughters how they felt about me writing about these subjects. They did not say: ‘Hush!’ They said: ‘It’s your story, you tell it,’ which was generous.

So I did. I wrote it all. I wrote it as though no one would ever read it. I wrote it LOUD.

After years of not speaking up it was hugely empowering.

I recommend it.

Catherine Simpson is a memoir-writer, novelist, poet and short-story writer based in Edinburgh.

Her memoir One Body was published by Saraband in 2022. It follows an earlier memoir, When I Had a Little Sister, (4th Estate) and her debut novel, Truestory (Sandstone Press)

In 2013, she received a Scottish Book Trust New Writers Award for Truestory. Her work has been published in anthologies and magazines, and broadcast on BBC Radio 4. She is a regular reviewer on BBC Radio Scotland’s Tuesday Review.

By Aman, Harleen, Mehwish, Sati and Simran

UK

As a group of British South Asian women, we have come together as part of the educatinggeeta writing group. We have spun our writing webs around the theme of ‘Wild Brown Women’. Reflecting on the concept of ‘wild’, we’ve engaged with life experiences that have made us the women we are.

This is our collective thread.

Women Who Run With Wolves

In the seminal text “Women Who Run With Wolves”, Clarisa Pinkola Estes states “No matter by which culture a woman is influenced, she understands the words wild and woman, intuitively”. I remember reading these words, the sentence buzzing around my body. Flashes of images ran through my mind: dancing until daylight in Ibiza; the dum-dumming of the dhol aligning with my racing heart at my best friend’s wedding reception; and that time I did something for me, where time stood still.

In the middle of the pandemic, my newly separated and broken heart got into a car and drove to a place where there were no other souls to keep me company. I escaped my cage and fell headfirst into sweet freedom. I revelled in my audacity, turning away from the voices in my old cage, calling me back to the safety of the Known. You see, Brown women don’t just drive off alone to a random location without rhyme or reason. I stood on a cliffside, looking out on a lake, wind howling. I had not dressed appropriately and despite walking for hours, I was cold. My hair whipped around me, lashing around my face. I had never felt so alive, yet so very alone. I leaned into this solitude, my heart feeling giddy in its freedom from society’s expectations of a woman - my soul dancing in its newfound Wild.

Written by Aman

Wild. Brown. Woman

Wild.

A word drowning with negative connotations. As though we are uncivilized, feral creatures unable to obey the demands of society.

Wild, to be associated with rebellion, breaking glass ceilings, untamed yet powerful.

Brown.

The colour of my skin. A colonizer’s dream. The exemplification of my race; a race which gives permission to society to oppress me. A shade which tells people I am their inferior, that my words do not matter.

Brown, to be associated with vibrancy and culture, language and food. A little bit of spice in this otherwise bland world.

Woman.

Second class citizen. Emotional and irrational creatures-God forbid we should be given the power to rule countries one day. Baby making machines.

Woman, to be associated with equality, success, multifaceted, boss babe. To show the world that my sex does not determine my worth.

For I am a woman. A Wild. Brown. Woman.

Written by Harleen

Wild and Sikh

I am becoming a Wild, Sikh, Brown Woman

I am finally ripping away the Poisonous messages of the Patriarchy

I am extracting the deeply, ingrained toxicity of colonisation

That had nurtured my sacred essence and forced me unconsciously to embody a Tame, Sikh, Brown Woman for far too long.

I accepted what I was told, never questioned, or raised my voice

I suppressed my true emotions and silenced my intuition

I stepped into the comfort of the shadows, hiding away my spiritual power

I had become a Tame, Sikh, Brown woman; compliant and complicit to all I saw that was unjust for far too long

I then encountered Motherhood

A spark of desire was ignited that everything needed to change

I began to understand my Sikh Spiritual and Ancestral roots

I connected with the stories of Sikh Warrior Women of my lineage

I started to walk on the pathway towards my Azadi*

I am healing and releasing intergenerational traumas

I am discharging the weight of unprocessed emotions and strengthening my intuition

I am stepping out of the shadows and declaring my spiritual power

I am wearing my Kara** and Kirpan*** to remind me of the immense Power I possess

As I am revealing my potential and capacity to be a Wild, Sikh, Brown Woman

Azadi- from Persian meaning Freedom/liberty

Kara- A Sikh article of faith, reminds me of the infinite nature of this world.

Kirpan- A Sikh Article of faith, a symbol to remind me to fight against injustice and oppression

Written by Sati

To be Wild

Maybe to be wild is to be free,

From the unforgiving expectations

Of an overcritical society,

When only the opinion of others matters,

Limiting your existence.

Maybe to be wild is to find your voice,

Against injustice and restriction,

Finding power in the very femininity,

Which chained your potential.

Maybe to be wild is to dream,

Beyond glass ceilings,

Of what is possible and achievable,

Without checking your reflection,

And beginning to unsee what others see,

Knowing you are more than:

Brown skin, diverse culture and ethnic clothing.

Maybe to be wild is having knowledge,

Gained through the wisdom of living and being,

Releasing traumas and burdens,

To heal and release,

Leaving and letting go.

Maybe being wild is an acceptance,

That survival takes all modes,

And happiness is a journey and not a destination.

Sometimes an elusive goal.

Maybe being wild is growth,

Through and beyond discomfort,

Heading lessons from life and people,

Discovering that there is always time to bloom

In the right environment.

Maybe being wild is finding peace,

In the laws of nature,

Away from imperfect rules of a world

Which should evolve faster for the modern brown woman,

Empowered in the truth that only you hold your power.

Written by Mehwish

A Wild Brown Woman.

They call me a wild brown woman for my hair is too long, too dark, too silky.

They call me a wild brown woman for my skin is the colour of the Assam tea they add milk to at afternoon tea.

They call me a wild brown woman for my clothes are vibrant, embellished and nothing like they’ve seen before.

They call me a wild brown woman for my eyes are deep and dark like the untamed woods that contrast the tranquil blues of theirs.

They call me a wild brown woman for their mouth cannot comprehend my name - it is a tongue alien to theirs.

And you…

You call me a wild brown woman for my daily menu is not dhaal and roti.

You call me a wild brown woman for my masala is a shade darker than yours.

You call me a wild brown woman for I converse with those whose ancestors once oppressed mine.

You call me a wild brown woman for feeding my child from my brown breast while sipping on tea at a tearoom.

You call me a wild brown woman for not being a submissive, silent wife.

You call me a wild brown woman for not walking paces behind my husband.

You call me a wild brown woman for powerfully keeping my name after marriage.

You call me a wild brown woman for speaking. For being honest. For having a voice, an opinion, a breath.

You call me a wild brown woman because my skin is like yours yet I am no mirror of you nor who you want me to be.

You call me a wild brown woman for being ferocious like a lioness protecting her cub.

But you’ll think again and when you call me a

Wild

Brown

Woman.

For soon my daughter will grow

And

You will call her…

A

Fearless Brown Woman.

Written by Simran

We are all members of the educatinggeeta writing group. Although our writing is connected through a common thread, we’ve interpreted the theme through different experiences. To be wild is to change and grow, enmeshing two cultures to create a new voice. We are the generation who change and now own the narrative. We are confident and empowered to live as independent, Wild Brown Women.

By Samantha Clark

January 2023

Orkney

Like stars, mists and candle flames

Mirages, dewdrops and water bubbles

Like dreams, lightning and clouds

In that way will I view all phenomena

Prayer of the 12th Tai Situpa

I live between saltwater and fresh. My home lies beside a wide freshwater loch that rests in a shallow bowl of low green hills. The burn that flows out of it skirts the edge of the garden. A mile from here it meets the sea that encircles this island. Most days, I walk from loch to sea and home again. Wind on my left cheek, wind on my right.

I watch the water. I’m trying to draw it. But here’s the catch; when you draw water you make it into something that bears no resemblance to water. You strip it of its restless, liquid reality. A drawing takes time and holds it still.

But you can’t hold water still.

I’ll keep trying.

This morning I’m sat here at my desk writing. I’m feeling for the right words as if with my fingers, the hesitant stumble and rush of them over the keyboard, the words that come so ploddingly, hopelessly trying to hold onto time, to pin it to the page. I don’t even know why I’m doing it.

I do know why I’m doing it. To try to hold still those dewdrops and water-bubbles, those dreams, lightning and clouds. To see if art can hold a single instant still, slow it down enough to see it properly, watch it slowly thicken with meaning. To see if I can know fully one moment, even an instant.

A drawing is a net for catching time. A sentence is a path attention follows.

So, I go on setting down words on the page. I go on drawing my tiny lines and circles. Millions of them. I bring my attention back each time it wanders, frets, worries, goes racing after distraction. I watch the water as it goes on circling and cycling, always going, always coming, always here, always already elsewhere. I watch my thoughts go spinning on and wait for them to settle. I try to learn patience.

And from that, I hope, will come a certain steadiness. Calm.

My fingers twitch in the air above the keyboard as if reaching for something. Time is too quick for me. Catch catch catch, always in arrears.

Acknowledge the impossibility of the task.

And keep going.

Stay. Just listen. On the shed roof there’s a starling chirring and whistling and buzzing through his whole repertoire, and further off a curlew’s long, weeping call. Further still someone is hammering in a fencepost. Chipchipchipchirrup go the busy sparrows. The clouds are gleaming today as if lit from inside. The bright beauty of this big sky, this towering cumulonimbus, will never come again just in this shape. This light, this moment, will never repeat itself. And yet it does also repeat itself. The daily cycle, the seasonal round, the regular chores. Make the coffee. Feed the hens. Answer emails. Mark another batch of student essays. Make a to-do list. Tick tick tick. Stir the soup. Butter bread and eat it. Wash and stack the dishes. Draw more circles, more lines. Write more words. And under the slow tumble of sky there is always the quickening shimmer of the loch in wind and sun. The sound of the sea coming from beyond the fields, a big swell still washing in after yesterday’s gale. Water, always, a dancing thing, a lightness. A strangeness.

I go out to check the hens, and stand a few moments by the lochside, holding a just-laid egg still warm in my hands, turning it over and over against my palms. This moment, resting so tenderly in itself. How full it is. The light pouring its freshness over everything. Greylag geese drift and preen. Gulls fly up off the water with clapping wings and shake themselves dry like wet dogs, midair. Along the shingle at the water’s edge oystercatchers lift and settle, lift and settle, piping loudly all the while.

Hold the moment like the egg. Cup it gently, feel its fragile shell and the warmth lingering inside it. How can I observe the inside of this moment without dropping or breaking it? I catch at the scraps, glimpse the edge of something, a trick of the light, the brief flash of a trout turning in the shallows and gone, the glint of a gnat’s wing. Life’s flow washes over and through us and yet somehow leaves us beached, gasping and flapping on a bare shore: Ralph Waldo Emerson puzzled over this: I take this evanescence and lubricity of all objects which lets them slip through our fingers even when we clutch the hardest, to be the most unhandsome part of our condition.

Where is it, this moment? It melts under the heat of my attention. It’s gone in the very instant of its becoming. If life is made up of successive present moments, each one ungraspable, how will I know I have lived?

I’ll keep drawing. I’ll keep writing. I’ll accumulate my circles, my layers and lines. I’ll feel for the right words. Then one day I might understand.

Samantha Clark is a visual artist, writer and creative mentor based in Orkney. She was awarded a Scottish Book Trust New Writers Award in 2018, a Cove Park Emerging Writers Award in 2020 and the RSA William Littlejohn Award in 2021. She has a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of St Andrews. Her first book “The Clearing” was published by Little, Brown in March 2020. She now lives beside, draws and writes about water.

Insta/FB: @samclarkartwrite

All photo credits Samantha Clark 2022

WILD WOMEN PRESS

CONTACTS

Email: vik@wildwomenpress.com