Thread 51 - The Red Dress - a collaborative embroidery project - Kirstie Macleod

Thread 50 - A River Flows Through Us - Dr Amy-Jane Beer

Thread 49 - The Story Apothecary - Nana Tomova

Thread 48 - The Penny Rolls On - Karen Penny

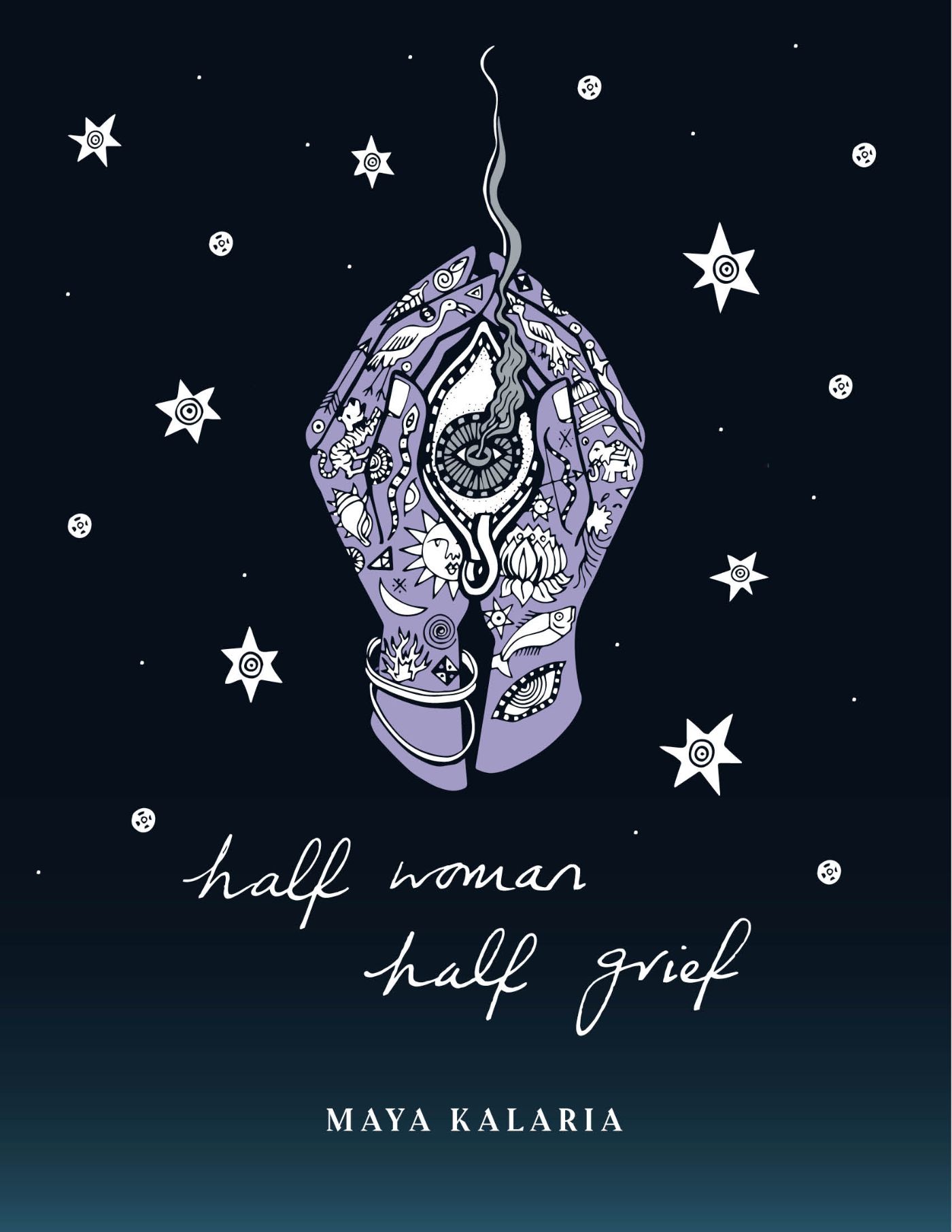

Thread 47 - The Defiance of Beauty - Maya Kalaria

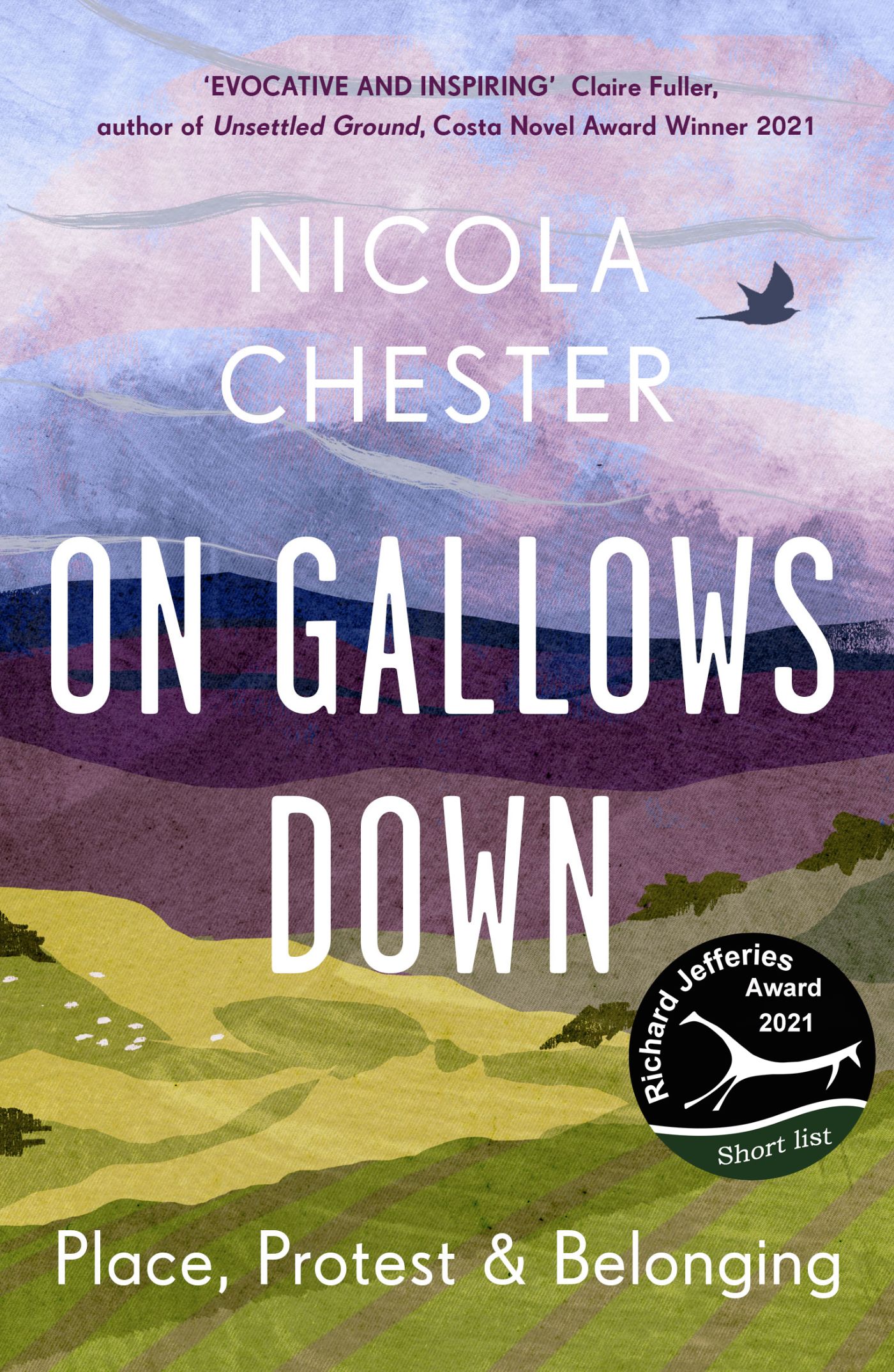

Thread 46 - What It Is To Be Wild (this woman's work) - Nicola Chester

Thread 45 - The Sea Library - Anna Iltnere

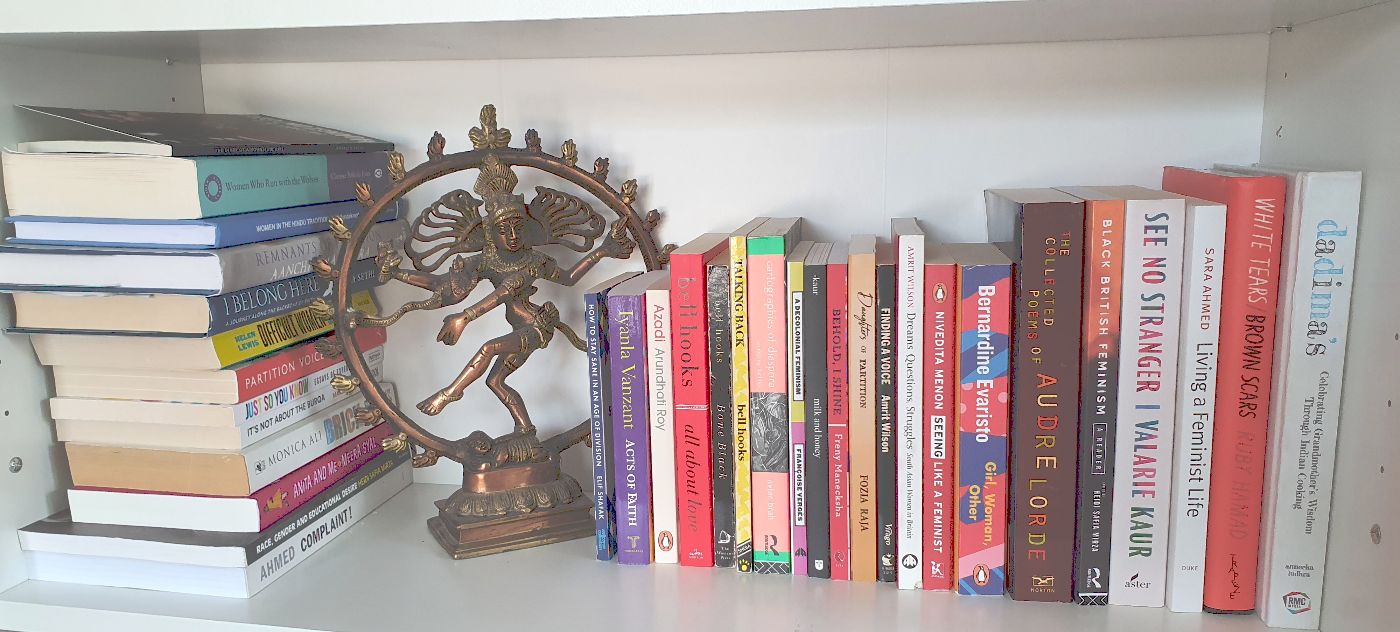

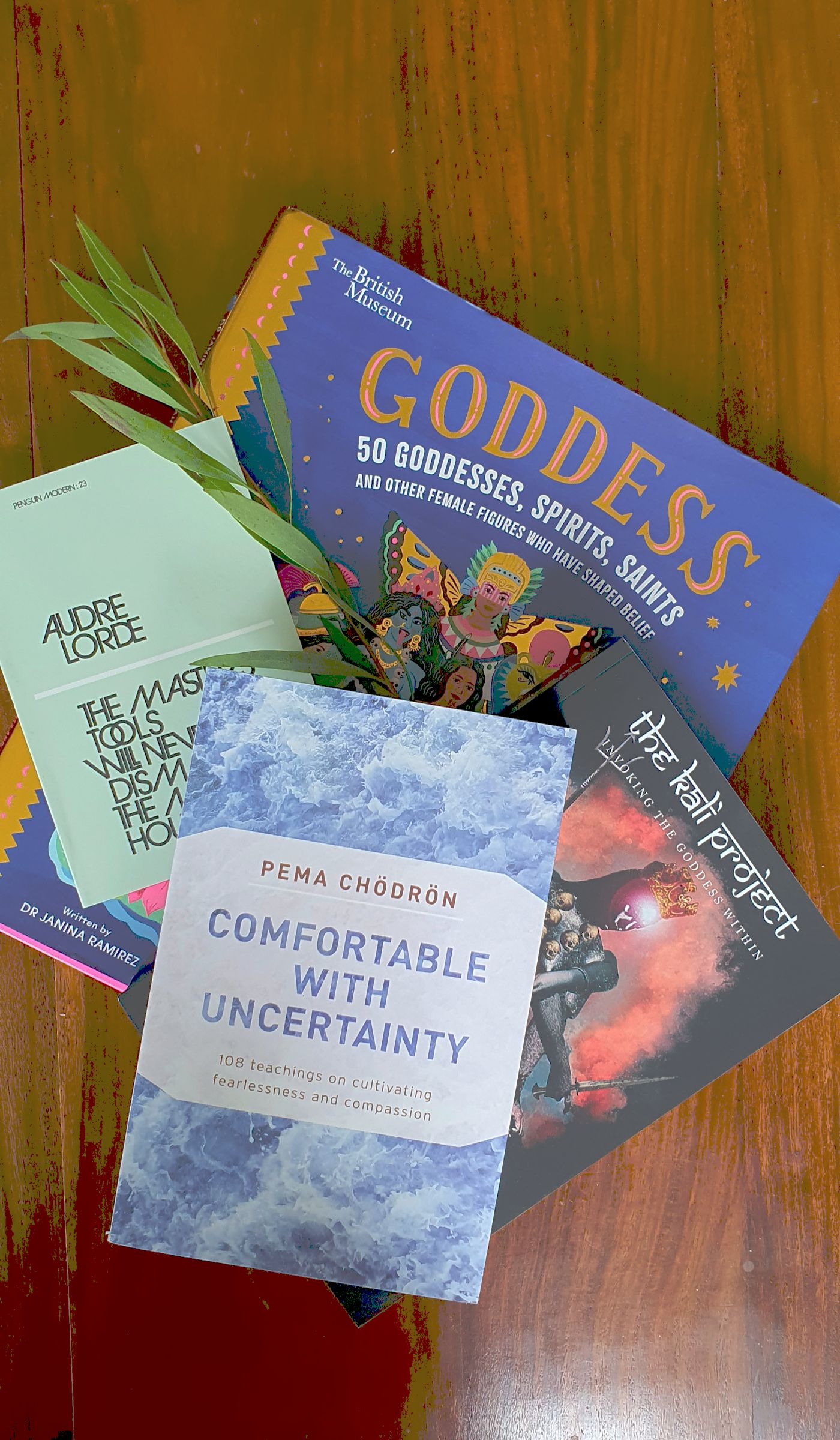

Thread 44 - Educating Geeta: Wild Woman Creativity - Dr Geeta Ludhra

Thread 43 - I do not yet know - Clare Archibald

Thread 42 - Sites of Transformation - Dr Louise Ann Wilson

Thread 41 - And they tip their heads back and howl - Tamsin Grainger

Thread 40 - Wild Plant Stories - Amanda Edmiston (Botanica Fabula)

By Kirstie Macleod

December 2022

Somerset, UK

"Any time women come together with a collective intention, it’s a powerful thing”.

Phylicia Rashad

The Red Dress is a 13-year, award winning global, collaborative embroidery project spanning from 2009 to 2022.

I felt moved to create the Red Dress Project to provide a space of connection and unity, and a platform for women’s voices to be amplified and heard.

Having grown up in various far-flung countries all over the world, I came back to the UK to study and following an MA in Visual language and performance began my career as a fine artist in London. My practice was rooted in textiles but expressed in unusual ways, and over the years I developed a language using high impact garments in film, animation, installation, and performance.

The Red Dress, the last of my installation works, was created in 2009 from a desire to initiate a piece of work that would draw together different identities and cultures from around the world, without borders or boundaries. A collaborative piece that would unite individuals whilst celebrating the universal language of embroidery and creative expression.

The garment itself is constructed out of 86 pieces of burgundy silk dupion and has been worked on by 347 women and 7 men, from 48 countries, with all 136 commissioned artisans paid for their work (as well as receiving a portion of all ongoing exhibition fees and merchandise). The rest of the embroidery was added by willing participants and audience at various exhibitions and events.

Embroiderers include female refugees from Palestine, Syria and Ukraine, women seeking asylum in the UK from Iraq, China, Nigeria and Namibia, victims of war in Kosovo, Rwanda, and DR Congo; impoverished women in South Africa, Mexico, and Egypt; individuals in Kenya, Japan, Turkey, Jamaica, Sweden, Peru, Czech Republic, Dubai, Afghanistan, Australia, Argentina, Switzerland, Canada, Tobago, Vietnam, Estonia, USA, Russia, Pakistan, Wales, Colombia and England, students from Montenegro, Brazil, Malta, Singapore, Eritrea, Norway, Poland, Finland, Ireland, Romania and Hong Kong, as well as upmarket embroidery studios in India and Saudi Arabia.

Many of the artisans are established artisans, but there are also many pieces created by first time embroiderers. The only brief given by me was to, in some way, express their identity and culture, and to use their own threads. Some chose to create using a specific style of embroidery practiced for hundreds of years in their family, village, or town, others used simple stitches to express powerful stories, reflections, and emotions from their past.

The Red Dress’s 13-year creation journey around the world is now complete, with the dress assembled in its final configuration. Covered in millions of stitches, the 6.2 kg. silk Red Dress is weighted as much by the individual stories and collective voices waiting to be heard as by the threads and beads that adorn it. The initiative has connected individuals from all walks of life, bringing comfort, raising awareness and I hope serves as a reminder to what is possible when we come together, supporting, and uplifting each other.

The Red Dress has been exhibited in various galleries and museums worldwide, including Gallery Maeght in Paris, Art Dubai, Museo Des Arte Popular in Mexico City, the National Library of Kosovo, an event at the Royal Academy in London, Fashion and Textile Museum, London, and the Premio Valcellina Textiles award in Maniago, Italy where it won first prize in 2015.

Moving forward, the Red Dress will be travelling to many different galleries, museums, and event spaces around the world - with a continued aim to be accessible to all. As well as bringing the garment to visit vulnerable communities and groups, I hope to display the Red Dress in the countries of the commissioned artisans - and exhibit the Red Dress alongside their own work in their chosen venue.

Practical and logistical support with commissions for the project was provided by the following charities, self-help development projects, social enterprises and various initiatives providing support to women in poverty: Manchester Aid for Kosovo supporting Sister Stitch in Kosovo; Kisany in Rwanda and DR Congo; Missibaba in South Africa; Kitzen in Mexico; Al Badia in Lebanon supporting Palestinian refugees; FanSina in Egypt and The Swansea Women’s Asylum & Refugee Support Group in Wales. Seed investment for the project was provided by the British Council Dubai in 2009 and subsequent funding has been received by the Arts Council Lottery Fund, the British Embassy Pristina, Kosovo and 2 Crowdfunding campaigns, UK.

Kirstie now lives in rural Somerset with her partner and children, balancing a simple life aligned with nature, yoga and meditation alongside the privilege of guiding the Red Dress around the world. You can find out more about The Red Dress, and follow its journey on instagram and facebook - all Press and Exhibition info can be found ononline at www.reddressembroidery.com

(Image taken from website)

By Dr Amy-Jane Beer

North Yorkshire

November 2022

I’ve spent three years following rivers and paying attention to what they showed me. The result was a book #TheFlow – rivers water and wildness, but also, and far less expectedly, a new version of myself.

In one of her lockdown lectures as Oxford Professor of Poetry, Alice Oswald said ‘the physics of water is metaphysical’, in that it both reflects and transmits. Just as water can carry so much more than itself, a river contains all colours and all moods.

Anyone who’s spent time on a riverbank, watching the water, is likely to find their thoughts wandering. Perhaps upstream and back in time, in search of origins, or maybe downstream, to the future and to consideration of consequences.

It’s hard to define a river. After three years thinking about, and increasingly like, moving water, I can say with certainty that a river is not merely water flowing in a channel. That water comes from somewhere, it is going somewhere, and one day, it will come back around.

It’s the same old stuff, flowing fast and slow through oceans and atmosphere; over ground as ice or liquid, underground between grains of sediment, fractures in rock; through the intricate veins of plants and animals, in and out of every cell.

For most of its 4 billion year existence on Earth, water dwells in abyssal or chthonic darkness. Often it finds itself bound by cold, now and then it is conscripted to biological processes. Just occasionally it gets to live its best life, quickened by gravity, lit by the sun.

There, in rivers, water finds its voice – or rather its voices: trickles and gurgles, fizzing and chatter, thunder and hiss. And these voices have compelled me to listen.

The stories a river can tell! Tales of deities and monsters, death and fecundity, heroics and folly, inspiration and exploration, flashes of terror and enlightenment, sublimity and joy.

In many indigenous cultures, rivers are considered self-evidently divine, and they have rights. In ancient Rome, they were ‘res publicae’ belonging to all citizens. The idea that they might be privately owned is as absurd and unnatural as it is selfish.

And yet here we are, in a country were individuals and private entities claim legal dominion over not only the bed, but the water. Along almost 97% of England’s rivers, if you swim, paddle, sit, row dip in a toe without permission, you’re liable to be branded a trespasser.

It’s just a word, really. But a heavily loaded one. It was a shock to discover that’s how the law sees me, or anyone that steps off a public right of way or designated access land without permission, or who lingers longer than the owner would like.

Virginia Woolf once imagined a world in which Shakespeare was born a woman – what would have been lost when her genius was unexpressed or ignored? I find myself thinking of exclusion from nature in similar terms. What potential is being squandered?

It’s not hard to imagine leaders with no understanding of nature – the current excuse for government appears to lack even rudimentary ecological literacy. But imagine they DID understand. Imagine nature being an automatic consideration in every decision.

When John Muir took Theodore Roosevelt camping in Yosemite Valley, the National Park movement was born. That is the power of reconnection.

Education, for all its importance, can only do so much. The skills and knowledge we share need context and passion to be useful. We’ll do for love what we could never be brave enough to do for money.

Meaningful time in nature will makes an activist of almost anyone. No wonder some don’t want us to have it. With humility, with respect, with open hearts and minds, let’s claim our birthright. Starting with rivers, because when you follow where they flow, they give you the world.

Amy-Jane Beer is a biologist turned naturalist, nature writer and campaigner. He latest book, The Flow, documents her physical and emotional exploration of the rivers of Britain through ecological, cultural and historical lenses.

By Nana Tomova

October 2022

Sussex, UK

There is a light drizzle outside my window. The last of the summer flowers are hanging their heads, as if nodding to sleep.

I treasure the childhood memories, and I still have dreams of these gardens, which as an adult look so ordinary, yet through the imagination of a child they were a portal to the world of possibility. The roses are no longer though, they have been replaced by a children’s play area, and the linden tree has been cut down. Nature discarded.

At the age of ten, I left the linden tree, the insect hospital, the trees I used to climb, with a rucksack on my back. My family left Eastern Europe to head West in search of a better life, success, and a brighter future. As I said goodbye to my beloved relatives and friends, we headed to foreign lands, planning to come back in a year and a day, with stories to tell. Except that we didn’t. That was the last day that I knew what feeling at home meant. Belonging is not something we think about unless non-belonging has shrouded us like a grey mist. At the tender age of ten summers, I made my way to France, and then to England two autumns later.

Ode to a Tree (original poem by Nana Tomova)

I feel alone in your roots

The loneliness is welcome to me

It is like the bitterness in the mouth that tastes so sweet.

The raindrops drum your body

The most natural and talented makers of music

Body against body

Life with life.

I see clearly with my eyes closed when I am with you.

I feel your wounds like you feel mine.

Your quietness plays the music in my soul

I find my roots when I see yours,

You show me the way home.

Safety, belonging, and sense of home were foreign to me then, even though I always received love, companionship, and subsistence. I was uprooted. I found solace in nature and stories, which although were in a language I did not speak very well, still gave me a beautiful place to go. But nature and fairy-tales were not given much credit where I grew up, and so they were put away to make way for more important things: algebra and science, French literature and history. And so I forgot them, until through circumstance, two decades later, I found myself in a little hut, learning the art of telling traditional oral stories. Thirteen of us, under thirteen wooden beams, I realised that for the first time in a long while, I was home.

How can we belong? What do we belong to? How can we allow belonging to find us? The word belonging is thought to come from an old Proto-Germanic word langōna, meaning to pine, to yearn for, to grieve for. That is how it has felt for me, and for the relationship with the natural and story world that I have now. The land and the old stories are some of my biggest teachers. They hold me tenderly, guide me, and at times take me to the dark underworld, from where I eventually emerge, my hands bearing gifts for myself and my community. Stories offer hope, courage, wisdom, and medicine. That's what they have offered me. That's what they offer to all who have the ears to listen, and the heart to let them in.

Nana is a traditional oral storyteller, a medicine woman, and a nature connection guide. She is a trained pharmacist, having worked in mental health for the last decade. Nana believes in the healing nature of stories, and hence in 2020 she set up the Story Apothecary Podcast, where she dispenses stories as medicine for the body, mind, heart, soul, and for the earth. Each story is a prescription.

Nana’s Story Walks in nature have been featured in the Guardian, and she is a big advocate for tales being told in the wild, where stories and nature become one. Nana’s work has been heavily influenced by Nature, both her original poetry and the stories she tells. She currently lives in Sussex, but her love of the mountains is calling her, and she plans to move to Scotland over the next year. Nana primarily tells traditional stories from Eastern Europe, translating and telling old Bulgarian stories into English. You can usually find her telling tales in the local woodlands, or online. She is currently writing her first book, full of healing stories.

Instagram: @nana.tomova

Image courtesy of In Feathers

Text & images by Karen Penny

September 2022

Gower, Wales

On the 21st of September 2021, I took the very last steps of my walk around the Coast of Britain and Ireland, finishing in 50 mph winds at the most northerly point in Britain, Muckle Flugga, on Shetland. With the wind blowing me over, as waves crashed over the lighthouse, I stood with tears running down my face watching a sheep chasing an otter over the cliffs. It had taken two and half years of walking to reach here.

I left my home in the Gower, Wales on the 14th of January 2019 and walked 10,500 miles around the coast of Britain, Ireland, and its Islands. My journey had taken me around Wales, over to Ireland to England, into Scotland and its wondrous islands, down to the Channel Islands and Isles of Scilly. On completing my journey, I became the first person to walk the whole of the British Isles. This accolade had never been my intention, the sole motivation of my journey had been to raise funding and awareness for Alzheimers Research UK.

We had lost two very close members of our family to this cruel disease. The charity is considerably underfunded and in order to raise as much awareness as I could I wanted to take on a challenge that would engage others and help highlight the need for more funding into research. By the time I had concluded my journey I had raised over £125,000 for Alzheimers Research and the donations continue to pour in today through public speaking events. Displaying a selection of over 40,000 photographs of my journey, I love recounting the stories of the people I have met and places I have visited. I do not rely on notes as I recall every day of my journey. Often an hour’s talk leads into two hours very easily. When you are passionate about something it is so easy to talk about.

When I set out, I had no experience of public speaking, I had never been interviewed on the radio, never appeared on television, had never written openly about personal feelings, had never worn my heart on my sleeve. Social media was a blur to me. I had had no training; my son rang me the day before I left and asked enquiringly of me whether I had packed my rucksack and walked with it yet? “Not yet” I replied. What a learning curve this walk became for me! I was just a normal person doing an extraordinary thing. I set out with an overladen rucksack keeping the sea on my left and just started walking.

I walked on my own fifteen to twenty miles a day. I left in the winter, walking into the wind and rain along the coastal path, finding somewhere to pop up my tiny tent when darkness set in. I survived on adrenaline. But as the days turned into weeks, and the journey developed, people would stop me and ask, 'Are you the lady walking? Are you the Alzheimers Lady? '. The radio would ring for an interview. I would call into schools and care homes, and talk about the experiences of my walk. Along the way, I was joined by others -- individuals inspired by the walk, the fire service, army, ambulance crews, WI, along with families of those affected by Alzheimers.

A following of a few hundred people turned into thousands and with it the donations. I started writing blogs about the journey, not just facts but stories and amusing reminisces of the people I met.

People asked me to stay with them, wanting to hear my travels and similarly to let me know about the history of the places I was walking through. What an experience and privilege it was to meet so many people, I stayed with crofters, farmers, artists, musicians, and lairds of castles. I slept on boats, barges, in hammocks and polytunnels, one night I was sleeping in a ditch or carpark, the next the floor of a fire station and the next with a generous host.

At the beginning I was reticent about staying inside someone’s home as I never wanted to be a burden to anyone, but a farmer once told me plainly 'If people offer you help, then take it'.

These were very wise words.

The walk was an extremely humbling experience, meeting complete strangers that took you into their homes and hearts and similarly into mine. More than anything it showed how kind people are. We never hear enough about acts of kindness.

I appreciate everything and everybody and take nothing for granted. I would not change a single moment of my journey. We live in such a wonderful place.

Many have called me mad for undertaking such a challenge, but M.A.D means 'Makes a Difference'.

We can all do that.

Karen Penny lives in the Gower in Wales. She is a prolific long-distance walker having walked various trails throughout Britain. In 2017 she walked the length of Britain from John O’Groats in Scotland to Lands End in England, a journey she subsequently emulated in Ireland traversing the length of Ireland from Malin to Mizzen Head. In September 2021 Karen became the first person to walk the coast of Britain and Ireland together with a further 110 islands. It took her two half years to complete her solo journey walking 10,500 miles. In the Spring of 2023 Karen embarks on another journey to walk the county boundaries of Britain and Ireland following the ancient highways and byways.

Karen is regularly interviewed on both television and radio and is currently drafting a book about her travels and experiences. A keen photographer she gives talks and presentations with a catalogue of over 40,000 photographs continuing to raise funds for charity. She is an Alzheimers Champion raising over £125,000 for Alzheimers Research UK.

You can find Karen on Twitter here

By Maya Kalaria

London, UK

I grew up as one of the only brown girls in a small town in Northern England. When I was nine, my mother died of Leukaemia, and my father quickly remarried my school friend’s mum; an English woman whose father had proudly served in the British Army in India, where my family originates.

The one brown woman who I saw daily, who looked like me, who gave me context within which to know and see myself in my unique beauty, was gone. I now shared both my intimate and external life with women who looked distinctly different to me. Small noses, fair skin, blonde hair and larger breasts were all I saw. I have always had a large nose, am more bones than curve, and was covered in thick, dark body hair. I regularly received racist comments from men on the street or the boys at school. The only difference was that now, the women in my own home couldn’t understand how excruciating that was.

What should have been a healthy initiation into maidenhood became a sharp and sudden descent into the underworld, which lasted for over twenty years. The ancestral rites and passages into womanhood which I would have received were gone. My grief took on a different shape - hidden in the shadows of my psyche, afraid and unsafe to be seen, yet increasingly desperate and rageful. Not only did I grieve for my beloved mother, but I also grieved for the parts of myself I had lost or willingly given up. Naive, vulnerable, and wanting to receive love which didn’t exist anymore in a neglectful, abusive household, my identity became obsolete. Our Gujarati food, our culture, our language - everything was gone in a heartbeat, replaced by dominant British cultural norms and practices - very few of which I resonated with, yet assimilated with out of fear of being further rejected and unloved.

I couldn’t see myself outside of me. It was only when I looked in the mirror that I received a nasty shock. At that stage, I had absorbed so many white beauty standards that I couldn’t see my beauty anymore, merely the many deficits which would inevitably prevent me from being loved by a man, which was sold to me by my stepmother as the ultimate goal in a woman’s life. The overarching, dominant white male gaze of the media was the only lens through which I viewed myself, and I developed severe body dysmorphia. No matter how many times someone would tell me I was beautiful in my later life, I could not receive or understand it, because I didn’t fit the criteria of beauty so heavily ingrained in my psyche as a young teen. My romantic relationships quite predictably became strained under the insecurities and gender dynamics which my psyche simply could not tolerate.

It’s taken some time to see that my beauty has existed as a defiant act. I do not fit the norms that I was given, shaped by the porn industry, racism and misogyny. Yet my beauty, I have come to know, still exists and is apparent to others. It exists as a delicate complex of individual physical features that I was told shouldn’t work, but inevitably do.

It’s only recently that I understood more fully how my physical Self powerfully reflects my life’s journey. As an individual, I have always lived outside of the norm. Having been initiated into the underworld at a young age, I have lived a life of social defiance and utter devotion to the unknown terrains of the wild mystery.

I believe, and have fought for, the expression of feminine energy far beyond the deliberately limiting and damaging confines of the male gaze. I have worked in the fields of domestic abuse, forced marriage and young people’s mental health, supporting the liberation of female-identifying people in their own defiance of constricting gender-based norms.

I have known the pain of being forced into boxes where I do not fit, being named with labels which do not describe me. I have known the joy and terror of bursting out of those boxes and ripping those labels to shreds. So why would my physical Self not challenge the neat categories of racist, misogynistic beauty ideals? It took me a while to finally realise the divine perfection of this alignment between my inner and outer Self.

If I had fit the cultural norms of beauty as a teen, I wouldn’t have faced rejection, and consequently wouldn't have come to know how the truth of beauty has been so wildly distorted. I would have experienced the world as a woman who ‘fit in’, who wasn’t singled out as un-beautiful as a young teen, and therefore could have comfortably lived within the confines of the patriarchal world for a much longer time, asleep in the illusory lull and complicity that often accompanies it. Instead, I had a rude awakening and spent my life scrambling in the dark, searching for a larger truth about what it means to embody feminine energy as a woman of colour in a neocolonial world.

And after all that, I can finally say this; I chose, and continue to choose, my Self in her full expression. I want to be witnessed in this body, with this face, by all the people I have known, and will ever know. I want my being-ness to challenge definitions of feminine beauty and power, just by my mere existence. To visibly reflect the legacy of my ancestors, as well as a truth much deeper and much more mysterious. To hold sacred the vast, ancient range of feminine expression in physical form. To be held in this sacredness. And to embody this truth every single day.

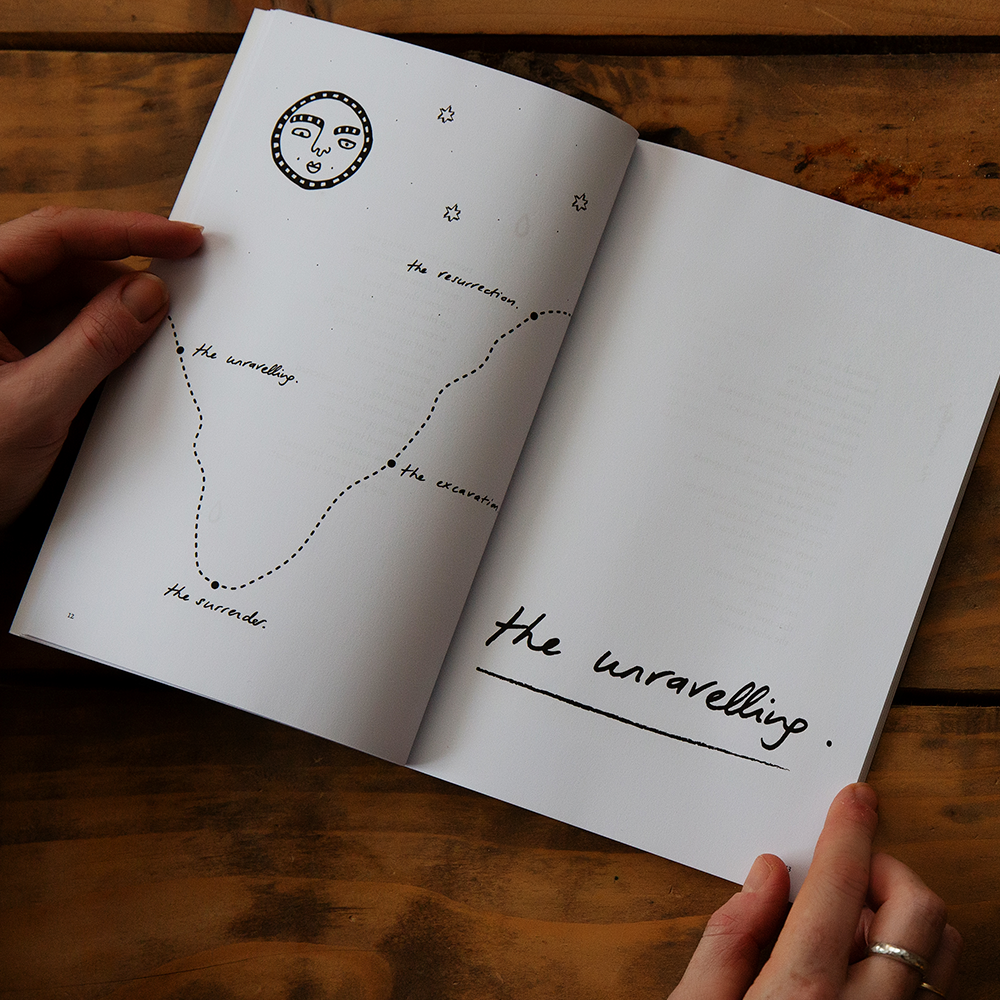

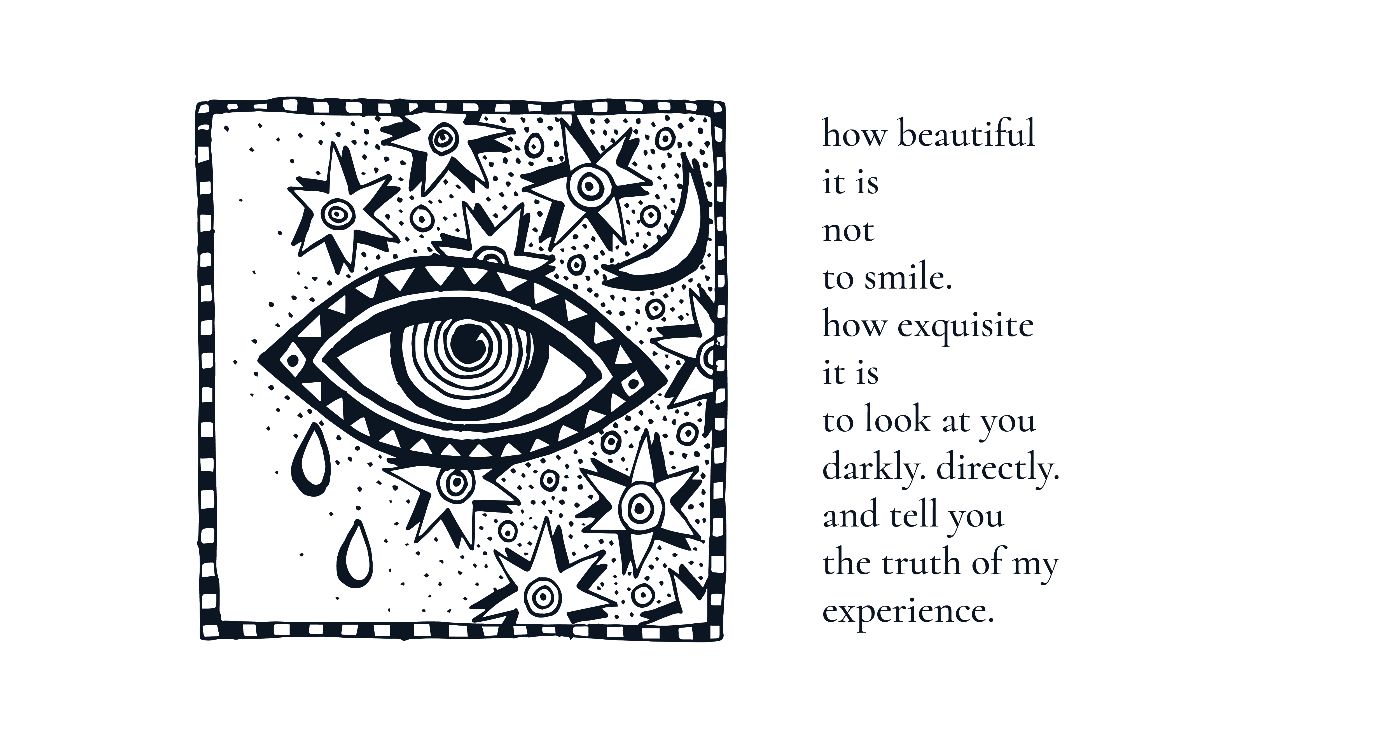

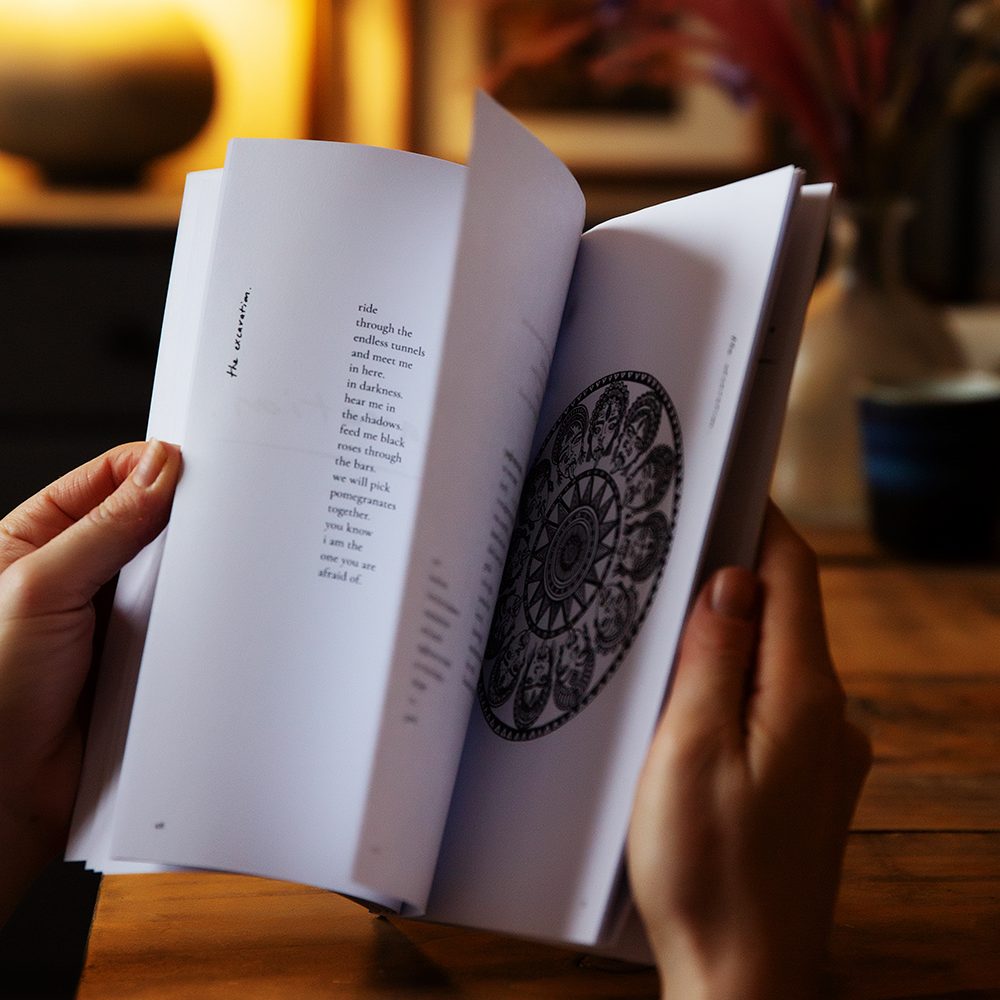

Maya Kalaria is an Author, Consultant, Educator and Astrologer. Her poetry book, Half Woman Half Grief, explores the hero’s journey through the underworld of death, grief, trauma and rage after losing her mother at the age of nine. As a lifelong intuitive and student of mysticism, she is also a qualified Horary Astrologer.

Maya recently co-founded Energetic Conversations with Daniel Edmund; a consultancy company helping to heal the racial, gender and mental health dynamics within company cultures.

Her wide-ranging professional background includes mental health practitioner work with young people, domestic abuse work with women and children, solution-focused hypnotherapy and retail management.

As a Gujarati woman born in England, Maya speaks powerfully about the racism and colonial trauma she experienced as a result of her early life circumstances, as well as the mysticism her life became steeped in through these life-altering experiences. She believes strongly in healthy communication as a powerful tool for healing and is passionate about connecting to our ancestral, indigenous roots, wherever we originate from. She also speaks of the energy work that she has practised for years, and is at the core of everything she does.

To find out more about Maya and her work, check out her linktree, follow her on Instagram or on Twitter.

(image by Genoveva Arteaga-Rynn. All images reproduced with knid permission)

By Nicola Chester

North Wessex, UK

July 2022

I am wild with the moon coming in through the curtains, laying an arm, a paw, a veil upon my bed so brightly. I kick at it childishly under the thin duvet, and turn over. It slides a finger coquettishly up the wall opposite. The intoxicating perfume of elderflower, honeysuckle and roses puff through the window, and intensify with the hour. The barn owl screeches (though softly) sssshhhhht, and I imagine it oaring through a silver night. The horses startle in the dark, their galloping thudding over an old, hoof-beaten earth. Song lyrics (from Kate Bush’s Big Stripey Lie) come into my head like a refrain; ‘your name is being called by sacred things that are not addressed nor listened to. Sometimes they blow trumpets.’ Yes, I think. They are tonight.

I do not want to be sleeping, but it’s a school night. I want to be out. I want to be galloping, jinking up the field and onto the down. The moon lies like an invitation, an open hand across my legs; a dare, a thin sheet of recklessness. I get up.

What does it mean, to be ‘wild’? Is it answering that calling, because I can? Is it, as writer Josie George puts it, in her beautiful memoir, A Still Life, ‘nothing so conveniently pleasing ... to be wild is to be wary, heeding instinct louder than promise … it is to steer yourself endlessly towards the things that nurture you.’ This really makes me think about what wildness is, and its place in our lives – in a woman’s life particularly - in work, family, community and even, in domesticity.

Is it, as I experienced one night after a rare, lone trip to London meant returning at one in the morning and walking through a dark, unfinished, mostly empty, multi-storey car park? The energy-saving lights came on, only as I stepped a foot into the next pool of darkness, then the next and the next, illuminating just a few metres of dark space ahead of me, that I’d already blindly committed to entering. I walked on through tight, enclosed stairwells and out through a boarded alleyway with shadowed corners until I reached my car, lonely in a small pool of light. I felt wild then. My senses on hyper alert as I realised I had made a poor judgement and felt unsafe, rounding each corner like a fox, slipping through shadows. Wildness is also to be alert, afraid and to want to go undetected.

The following night, I don’t wait for the moon’s invitation across my duvet; I go, into the June glow of a midsummer night on the downs, with my three children. My son is home from university – my eldest daughter has just turned eighteen and we celebrate with my youngest by running up the hill behind the house. Watching them, breathless with laughter, I think about the stepped over, trespassed and blurred boundaries of work and life and womanly wildness.

My work has never been contained by one job – it has always spilled over, or fallen between stools of paid and unpaid work. As a cleaner, or working with horses or as an unofficial wildlife conservation adviser, work, care, pleasure and duty blend and twine together into things that just must be done.

At work as a School Librarian, I am also motherly and a caregiver, first aider and mental health link – a giver, too, of just the right bookish prescriptions and balms. In my role as marketing officer, I celebrate, encourage and champion the efforts of our school ‘family,’ and in the clubs I run – Writing, Book or Eco Club - I reach out to the wider community, making connections, forging links and urging it on. I am a cheerleader, trying to include everyone and everything, spreading myself too thin, perhaps, to be fully effectual.

This is all perhaps most apparent in my writing work. I write to tell stories of resistance to wild losses; of how we can stand up for nature and each other, protecting our shared nest, our neighbours, human and wild, keeping house and a habitat for all.

It is a kind of domesticity that knows no bounds. It is not restricted to ‘in.’ It is not restricted to home or work; it extends its reach beyond walls, doors, fences, time sheets and the baffling irritant of clocks and timekeeping. I see that the women of this parish have almost always done this and I step outside of the boundaries in solidarity with them, too. The world is a nest we must sustain; one we can all live in, care for as a community, a family. And whatever the wildness means, at any given point, we’d do best to listen.

Nicola Chester has been writing about the joy and importance of nature since she was a child. This became a revel and an activism when a road was built through her wild childhood playground in the 1990s. She writes for the RSPB, is a Guardian Country Diarist and her memoir, On Gallows Down: Place, Protest and Belonging recently won the Richard Jefferies Award for Best Nature Writing, 2021 and is shortlisted for the 2022 Wainwright Prize. She lives with her family as tenants in a farm workers cottage, in the North Wessex Downs.

Twitter @nicolawriting

By Anna Iltnere

Jūrmala, Latvia

June 2022

It wasn’t always like this. It never is as it was. One morning the beach is ribbed by the wind, the other – licked smooth by a long wave. I never know what to expect when I arrive with my bicycle. I can only slightly guess what the sea (and sky and sand) will look like today. I’m often wrong. The sea keeps surprising me. It’s one of the reasons why I keep coming back to the beach. Yet there are so many other reasons, too.

It wasn’t always like this, but right now I am a sea librarian. It is a job that the sea, I believe, had imagined for me. I just had to arrive at the right time following my own inner tides. Ten years ago, I had to arrive at a century-old riverside house on a pine-covered peninsula between Lielupe river and the Baltic Sea. In a Latvian city called Jūrmala or Seaside if translated.

I come from the worlds of art and writing. I grew up playing on splintered wooden floors splattered with oil paint while mum painted and dad worked on his art installations. I didn’t like to draw. I was obsessed with reading. As a little girl I created my very first library. I wrote numbers in the corners of endpapers and listed my collection in a notebook with ruled pages. I was trying to create an order in the microcosmos of wild and tangled stories. I felt responsible to look after the books. To find readers for them among my dolls and teddies. To read them myself.

Life took me sideways. When I grew up, I was convinced that all I am good at is writing about art. And yet I felt that deep inside me is a voice that hasn’t spoken yet. When I turned 30 and was pregnant with our second child, I found myself being out of job and living in an old house on a peninsula between river and sea. We didn’t live in the capital city anymore. We didn’t commute loud and busy streets anymore. With no obligations and a chance to choose once more, I became a little girl again. I returned to books and kept reading about the wide open sea in front of me. It made me curious.

In a couple of years spent on a pillow of maternity pay, I had collected a library of my own again: one hundred books about the sea. I felt responsible to look after these books. To find readers for them. It was time to open the doors. It was June four summers ago when I invited first strangers into our home, to show a unique room inside it. A room full of books where stories about the sea lived. I was here to look after a microcosmos of it all. Over the years strangers from near and far have become my friends. Love for the sea unites us as a secret password. There are more than 600 titles on shelves now. Sea Library is a magical journey, a voice of my own.

Irish artist Dorothy Cross says in one of the books of the Sea Library that sea is a wordless place. “Being in water .. removes you from language.” I remember it whenever I swim. Yet we, human beings, are storytelling animals. We make sense of the world around us only by telling stories to each other and to ourselves . We write words about the worldless water to understand it’s push and pull. For me it’s a wondrous contrast. To stand here, on this thin line, the changing coastline between land and water, between stories and the unspeakable.

The sea is changing the land. It can also change us. I once got high on moving too far too fast. Now I get high on being slow by the sea. Ever since we moved, I have stayed. Like a compass grass drawing sand circles in sea breeze.

I stand on the coastline between land and water collecting stories that are trying to make sense of the sea. Years have passed, and the sea still doesn’t make any sense to me. I sit on one knee in the sugar-like sand writing down words in my notebook about the sea. I count gulls and mention my beach finds. I describe the smell of the washed-up seaweed and quote Joseph Brodsky about seaweed and happiness. Grey clouds are growing in size above me and suddenly it starts to rain. Water droplets make my writing wet. Some words in ink have shapeshifted into unreadable blurs. I am afraid I will never understand the sea. Yet, understanding is just one of the reasons why I keep coming back to the beach. There are so many other reasons, too.

Anna Iltnere is based in Jūrmala, a small town on the Latvian coast, where she opened a library in the summer of 2018 focusing on books about the sea. She receives copies from all over the world. There are now over 600 books in English, Latvian, French, German and Russian, including a book on boatbuilding from 1909, the oldest copy in the library, donated by a retired local captain. Coming from a family of artists, architects and actors, and formally a journalist covering the Baltic, Russian and Scandinavian contemporary art scenes, she now follows her passion – a life by, on and in the sea. This experience has led her to write a memoir about her post soviet bohemian childhood, her early life as a successful journalist travelling the world and then her decision to leave this lifestyle behind, and with her partner and young family move to a remote house on the Baltic coast. She is now looking for a publisher and weaving colourful bookmarks and blankets for readers.

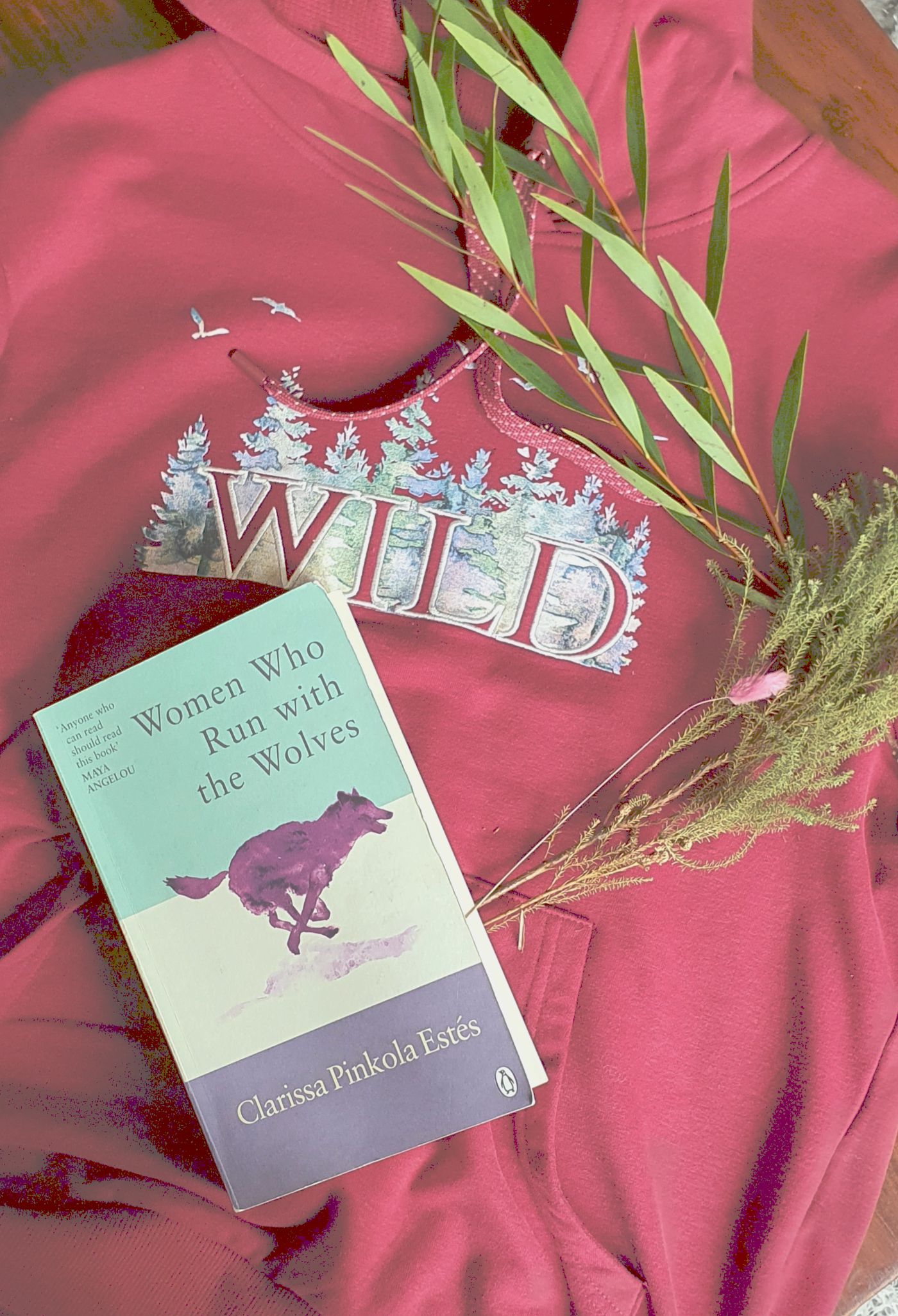

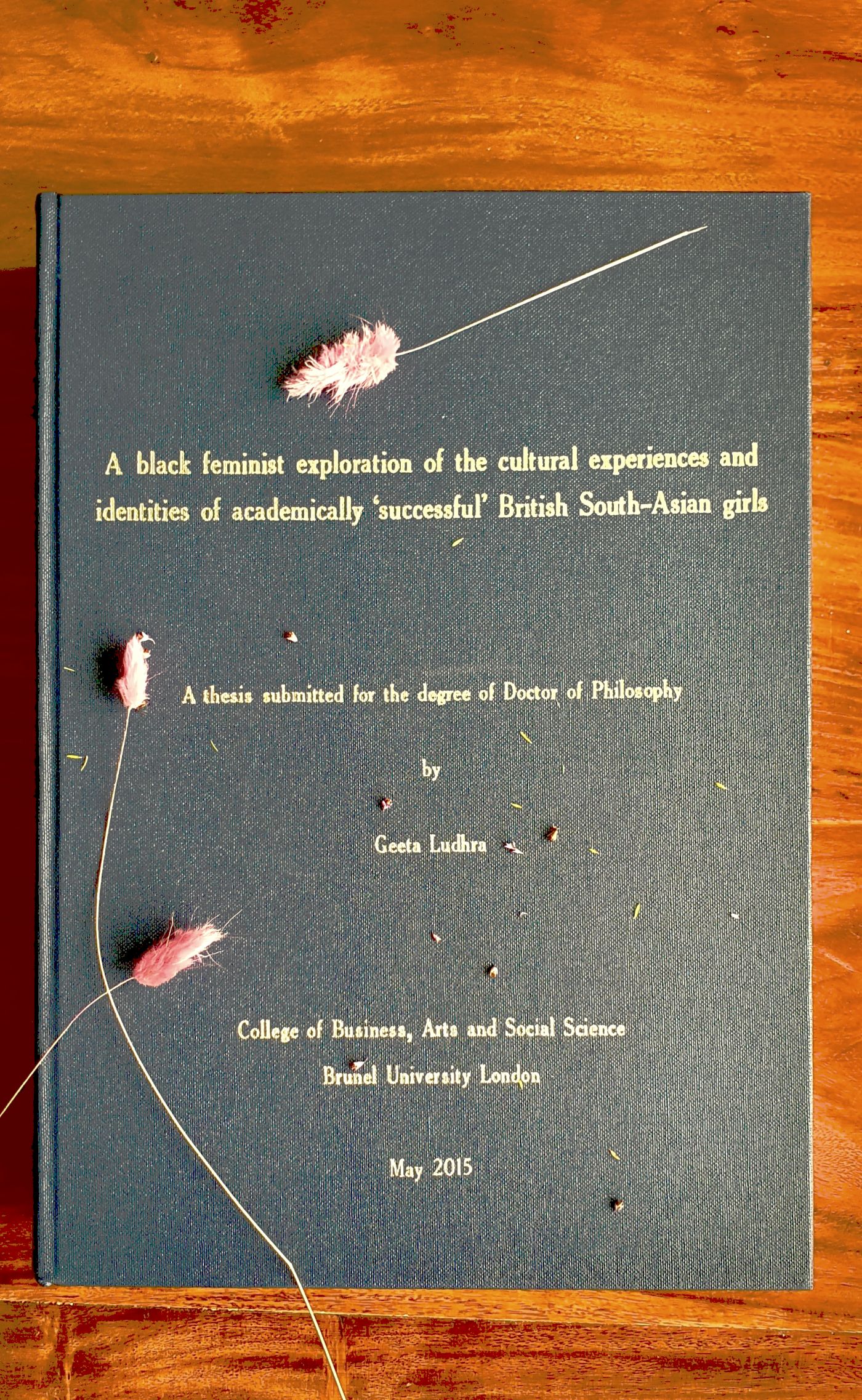

By Dr Geeta Ludhra

Chilterns, UK

May 2022

Creativity -- the wildfire in my belly that lights my soul, vibrates my mind to think differently.

Creativity -- embracing parts of my heritage, culture and femininity to find joy and freedom to explore and express.

Creativity – a space where the magic happens.

Knowledge – the books, people and life wisdom that guide creative transformation over time and place.

I return to an old journal article that I wrote on creativity in Teacher Education (Ludhra, 2008). The prescriptive style of academic writing makes me feel uncomfortable as I struggle to make words sit neatly and intelligently, trying to meet the prescribed criteria. As I read the paper, I realise how much I’ve moved on, but appreciate the bit that I wrote on the synergy between knowledge and creativity, and how they should perhaps be seen as mutually dependent. I state that ‘creative impulse seeks to break new ground and requires transformation’ – and that I have. My relationship with creativity and knowledge is a complex yet exciting one – when the two dance in harmony, my soul feels wild and happy – in a geeky ‘Educating Geeta’ kinda way (that’s my Indian spin on the 1983 movie ‘Educating Rita’).

My books are creative friends – I play with them, making them look pretty and welcoming on the bookshelf I always craved as a girl.

I’m not a ground-breaking woman who is overly adventurous – I take fairly comfortable risks that keep me safe. But slowly that’s changed, as I lean into the creative opportunities and metamorphosis that female aging offers. Although painful, the menopause has been part of my creative journey, where I’ve given myself permission to carve new spaces as a form of joy and self-care, essential to my thrival. These spaces have allowed me to transform and move forward with warrior-like hope.

‘Creativity is a shapechanger…Some say the creative life is in ideas, some say it is in doing. It is in most instances to be in a simple being” (Pinkola Estés, 1992: 313).

Over time, I’ve moved creative ideas from my imagination to action -- through the senses and psychic feminine intuition. Small acts have led to wild soul transformations, new voices roaring from silenced years.

My creative activities and spaces are simple and feel sacred – the energy generated through the learning and growth feeds my soul, but also my family and the communities I support. When I over-feed and nourish others, I’m ‘gasping for creative energy’ (Pinkola Estés, 1992: 315). I’ve learnt to reflect on my environment and interactions with people, to unblock the chakras and promote energy flow, rather than hosting everyone’s woes. As a woman who has always given and people pleased, stepping back, stepping away and putting up boundaries has felt like a light form of resistance, almost revolutionary.

So where do I find these spaces for Educating Geeta to feel wild, to thrive through the synergy of creativity and knowledge?

* I read books by feminists of colour who speak from a shared ‘truth’ of experience, providing authentic points of connection. I make it my business to educate myself daily to keep the wildfire alive; the Doctorate was an important point in igniting this wild feminist fire.

* I create and lead a reading, writing and walking community where like-minded souls connect. By creating spaces that I couldn’t find, creative energies dance together and vibrate at a higher frequency. As I walk and talk through the countryside as a woman of colour, alone and with people from diverse backgrounds, gentle steps lead to personal and community transformation (Changing Perspectives in the Countryside: Dr Geeta Ludhra - The MERL)

* I play with poetry and feminist theory, honouring my autobiographical experiences and the ancestral wisdom of my great grandmothers. I see this as a form of creative academic expression (I am currently leading a community writing book by South Asian female women, as part of the @educatinggeeta writing group).

* I cook like an Indian dadima (grandmother) who needs no recipe but is guided by her senses and intuition. I crush whole spices for my tea like an Ayurvedic teaologist, connecting to the ancestral culinary wisdom of wise grandmothers before me

* I pick up a paintbrush and teach myself how to watercolour, forgiving myself for those beginner ‘mistakes’, moving away from seeking perfection, focussing on simple creation.

* I connect with feminine energies that open my chakras – people that vibrate a creative flow, rather than absorbing and leaving me empty.

* I chant the Gayatri Mantra prayer in the privacy of my sacred space, to open paths that were once blocked. My chanting acts as a form of release to channel creative energies. I connect with the Hindu Goddesses as I return to my roots and honour their wild creative spirits through Mother Nature’s roots.

Geeta is a British-born South Asian woman of Hindu religious background. She is the daughter of first-generation Indian parents who migrated to the UK during the early 1960s. Her working-class background, along with gendered and racialized experiences, have led her to explore auto/biographical feminist writing that creates space for women of colour to creatively write their stories to raise awareness, educate and shape change. Geeta has two grown-up daughters and works as a Lecturer in Education at Brunel University. Geeta also leads a community social enterprise called Dadima’s CIC, which focuses on encouraging diverse walking communities in countryside spaces, and supporting South Asian female writers. ‘Dadima’ is the Hindi noun for paternal grandmother, and it was chosen to encapsulate the wise grandmother figures and ancestral knowledge across cultures and faiths. You can read more via her social media pages below:

Instagram: @educatinggeetachilterns @_dadimas @educatinggeeta

Twitter: @educatinggeeta

Geeta is currently developing a Dadima’s website.

(All images supplied by, and reproduced with the kind permission of the author)

Text/images by Clare Archibald

Fife, Scotland

April 2022

Everything is always a becoming or unbecoming and I struggle with the parameters of definition. With the need to state who you are and what you do or have done. The artist statement. The biography. The headshot that must meet other people’s expectations of the representation of the self that is yours.

I should tell you that I do not consider myself to be a wild woman, nor do I think of others in that way except perhaps frivolously on a particularly raucous night out or when singing certain songs.

When I look back on what I do or have done I see acts of repetition that are a misnomer because they are always different, yet it is how I describe them. Descriptions are not always what they seem. I should use these words to tell you what I do and what it means. Promote myself or at least my ideas or artifacts.

Except I simply do not want to. I would like to not have to be defined in order to have meaning or connection. Yet I believe in my work and that it is about more than me even when the central focus may appear to be me, even when I am erased by my own action or inaction. I reject the notion that I must tell you my meaning even though I also do not believe in manifestos. Who do I believe I am is the question that haunts me, us all perhaps. Or possibly not.

A haunting that is the intersection of private and public, real and imagined, individual and collective.

The to and fro of inside and out, the boundaries of the body.

I coexist with words but do not believe in them all in singular or multiple configurations. I repeatedly test this hypothesis for reasons unknown to others. Or yet myself. We could call this acts of compulsion, of interrogation, or if feeling sentimental, which I generally abhor, wonder. Or we could even call it alone.

I delayed writing and making until I was too old to do everything that I have not yet realised I want to do because I knew always that once I started I would not stop until the end point of understanding which is perhaps death.

I have straddled the time punctuated points of life and death, also felt the metronome of breath heat motion.

These are the points of transformation held forever in everything we think of as a second.

In thinking about transformation it is, I would argue in my non-existent manifesto, impossible to ignore the impact of light, to not contemplate the complexities of darkness. Especially because this is a cliché, a word that surely nobody likes.

You might think my nature is contrary and you would be right unless you considered it in the context of me and then we have the question of whether or not it is possible to be contrary to the self.

And even though I am not unique in many ways your self is not mine in a bundle and we will always be alone on some level of unfolding. I would like to know what the means for you without you having to tell me.

I do not write these words with you in mind but of course I would like you to find meaning in them.

Although I do not want to act from ego that is a choosing that could lead to extinction, to erasure of the self and I think this is what I meant in the old notebook that I found from when I was young where everything was divided into columns marked the nature of being (nob) or the double bind of life (dbol).

If I tell you this it does not make it true except perhaps for me. If I show you this you can decide for yourself. If you listen to it what do you think you are really hearing. If you touch it then I can only guess at what you are feeling.

Would you call this a treatise or a precipice of what is next. I do not yet know.

Clare Archibald is a Scottish writer living in coastal Fife. Her work incorporates text, sound, image, materials, performance and installation. She is preoccupied with ideas of articulation, place, what of the private we make public and why, movement, transformation and the potential of collaboration. Widely published, she has read and exhibited her text, image, and installation work at literary festivals, galleries, academic conferences, car parks and woods. In 2020 she made and scored her artist film, Can You Hear the Interim, as part of her multimedia project The Absolution of Shyness.

In February 2022 she released Birl of Unmap a collaborative album responding to a former mining/unfinished Charles Jencks land art site in Fife with fellow Fife artists Kinbrae, which is being performed in April 2022 at the Queens Hall, Edinburgh (see also the album-related t-shirt collaboration with We Are 1 of a 100 ).

She also set up and runs Lone Women in Flashes of Wilderness, a collaborative project exploring all women’s ideas on and experience of aloneness, darkness and wilderness in real and imagined terms, most recently undertaking a commission from Sanctuary Lab for a 24 hour installation in Galloway Forest of words, sounds and music from 140 women from across the world.

Clare is currently working on several solo and collaborative projects

(All images used are the copyright of Clare Archibald and must not be reproduced or used without permission from the artist)

By Dr Louise Ann Wilson

Lancaster, UK

March 2022

Last month my new book, Sites of Transformation: Applied and Socially Engaged Scenography in Rural Landscapes, was published by Bloomsbury Methuen.

In the book, I examine the development of scenography as a distinctive type of art and performance-making practice that seeks tangible, therapeutic, and transformative real-world outcomes. Using case-studies drawn from the body of site-specific walking-performances I have created over the last decade, Sites of Transformation demonstrates how I use scenography to emplace challenging, marginalizing or ‘missing’ life-events into rural landscapes – creating a site of transformation – in which participants can reflect-upon, re-image, re-imagine their relationship to their circumstances. These works have been created on mountains, in caves, along coastlines and over beaches.

Further, Sites of Transformation reveals my creative methodology and application of three distinct strands of transdisciplinary research into the site/landscape, the subject/life-event, and with people/participants affected by it. It also explores seven ‘scenographic’ principles that I have developed for the creation of ‘scenography with purpose’. These principles are underpinned by the concept of the feminine ‘material’ sublime, and informed by the attentive, autotopographic, therapeutic use of walking and landscape found in the work of Dorothy Wordsworth (1771–1855) and her female contemporaries, in particular Charlotte Smith (1749 –1806) and Ann Radcliffe (1764–1823).

Written between 1800 and 1803 while she was living at Dove Cottage in Grasmere in the Lake District, Dorothy’s Grasmere Journals log her everyday life, and are full of vivid descriptions of people, landscapes, sights, sound and noise, tactile sensation and kinetic bodily feeling. They show an awareness of changes in temperature, weather, season, emotion and mood. They are dynamic, non-static and overflowing with different kinds of motion: her own motion as she moves in and through the landscape – skidding on ice, crawling on all fours, lying in fields, woods and trenches, swinging on gates, scrambling up valleys in search of fungi or a waterfall, and the motion of the landscape as it shifts and changes around her – as clouds gather and streak the sky, drenching rain falls, flowers spring forth, trees stir in the wind or fall in a storm, the moon waxes, crows fly overhead and the darkness of night falls.

Not only did Dorothy’s walking practice and writings inform the seven scenographic principles but I used it in Warnscale: A Landmark Walk Reflecting on In/fertility and Childlessness (2015), as a framing device designed to frame and immerse participants in the landscape.

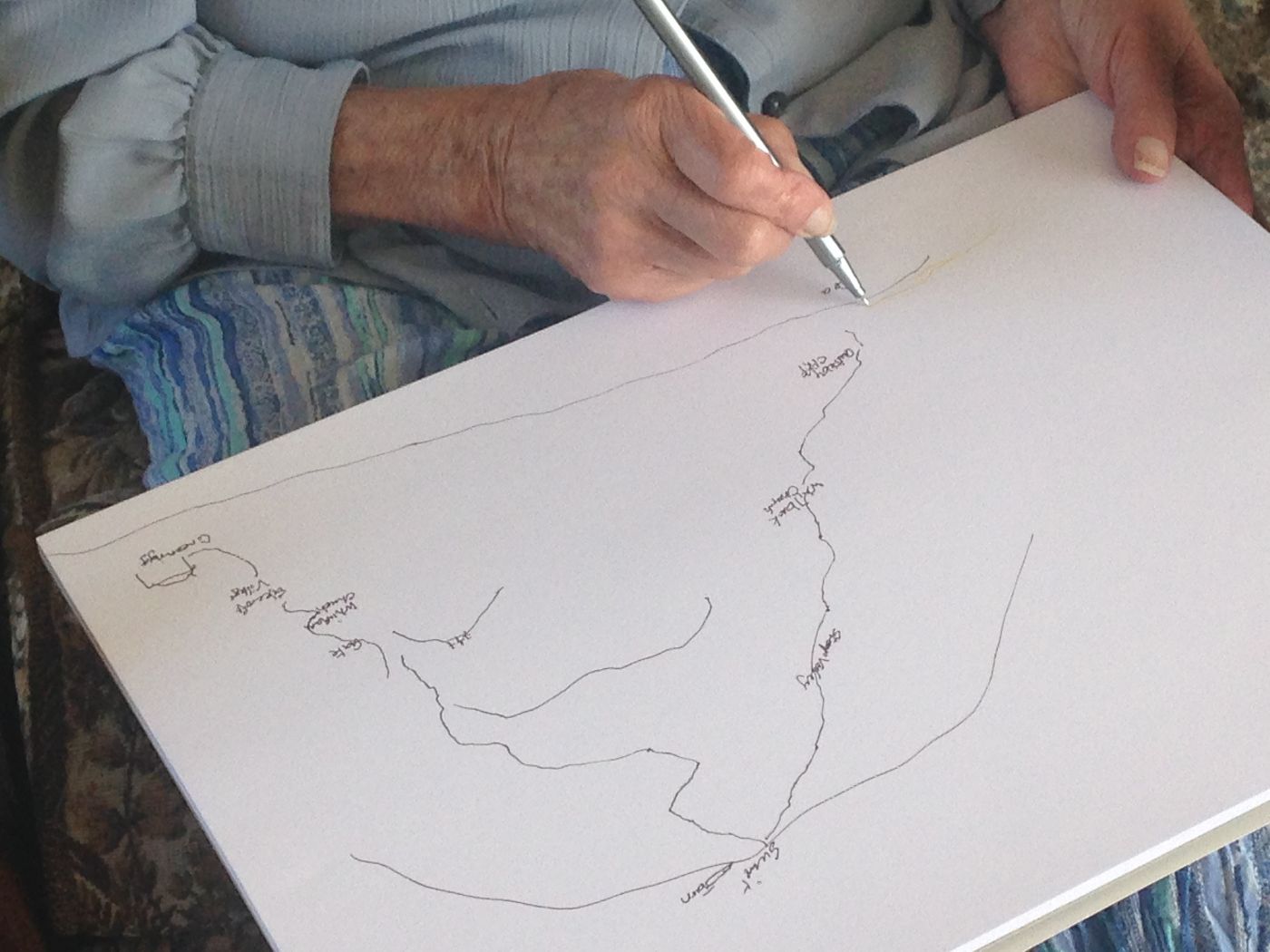

Written thirty years later, between 1831 and 1835, when she was living at Rydal Mount near Ambleside and was no longer able to walk, Dorothy’s Rydal Journals reveal her therapeutic use of memory-walking to access longed-for landscapes. It is these journals that informed Dorothy’s Room (2018), an immersive multimedia installation created in her bedroom and Women’s Walks to Remember: ‘With memory I was there’ (2018–19), a participatory project that memory-mapped routes present-day women could no longer walk.

The image on the cover of the book is from Fissure, a three-day long walking-performance in the Yorkshire Dales that took the form of a pilgrimage, that I created in memory of my sister who died aged 29 of a brain tumour. Using a combination of sung-poetry, dance, music, visual installation incorporating materials of the site, and neuro-scientific and medical interventions, I emplaced my sister’s illness, death and the grief caused by her loss into the landscape – which became a multi-dimensional and sensory scenographic environment . Moving on foot, participants circumnavigated Ingleborough Fell, traversed its limestone pavements, crossed its shake-holes, moved through its gaping ravines and scars, and followed rivers into the subterranean darkness of its caves. These topographies were chosen for their fissured-symbolism and dramaturgical echoes of how the Easter Trideum moves from life to death and light to dark. As they walked, participants encountered creative and scientific interventions made by dancers, singers, bell ringers, neurologists, oncologists, and geologists.

At dawn, on the third day, the performance resurged/resurrected from the cave-dark and ascended Ingleborough Fell – known as the Cairn of the Angels – from where an expansive view over Yorkshire, The Lakes and Lancashire can be seen. However, the wind – a force beyond our control – blew up and caused us to retreat from the mountain before the summit. Reflecting on this later, one participant said:

[..] the piece tested my body’s limits and on that climb on day three I could not help wondering what it must be like to be so ill that your body is tested to the limit and to the end.

It was this work that showed me how scenography can weave, distil, and image life-events that are hard to give-voice or words to, and led me to recognise the transformative potential of rural walking-performance.

On March the 8th 2020 (just before the national lockdown) to mark my 50th birthday I climbed Ingleborough with a group of friends. This time, despite the winds attempt once again to blow its visitors off the fellside, we made it to summit where we drank whisky, ate cherry cake, and sang the poem written by the poet, Elizabeth Burns, and set to music by the composer, Jocelyn Pook, for Fissure, and this site:

And now spring turns to summer

the year opens its arms

to lightness and warmth

turning and circling over again

turning as our hearts do

broken and mended, grieving and healed

moving from the bleakest night

towards the sunrise

the world spread out around us –

north, east, south, west

Ingleborough Cairn of the Angels

This year, to celebrate my birthday and International Women’s Day, I plan to walk with a group of women friends, and, to mark the 250th year of her birth, I will read Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere journal entry written on March 8th 1802. In it she describes the valley and lake in vivid painterly, detail and how, whilst still walking, she read a letter from a friend then sits to read another. Her entry finishes with her remembering how, ‘on Friday Evening’:

the Moon hung over the northern side of the highest point of Silver How, like a gold ring snapped in two & shaven off at the Ends it was so narrow. Within this Ring lay the Circle of the Round moon, as distinctly to be seen as ever the enlightened moon is (Wordsworth 1991: 76).

I have asked my friends to share the writing of a woman who has inspired them, and I extend that invitation to you: During March, consider walking – physically or in your memory – and sharing your own words or those of a woman who has inspired you with others. Also, as you go, spend time observing the detail of things, and the moon.

Reference

Wordsworth, Dorothy ([1800-1803] 1991), The Grasmere Journal and Alfoxden Journals, ed. Pamela Woof, Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1897 by Ernest De Selincourt.

Dr Louise Ann Wilson is an artist/scenographer-researcher who creates site-specific walking-performances in rural landscapes that give-voice to ‘missing’ or marginal life-events – with transformative and therapeutic outcomes. Her work has addressed terminal illness and bereavement, in/fertility and childlessness-by-circumstance, (im)mobility and memory, and the impact of change – personal and topographical. Each performance is transdisciplinary and developed in close collaboration with people who have knowledge of the chosen landscape and/or the underlying life-event subject matter, including those experiencing it. She is the author of the book Sites of Transformation: Applied and Socially Engaged Scenography in Rural Landscapes (2022). Her most recent performance works is Tell it to the Bees (2021) and Walks to Remember During a Pandemic (2020–21). Twitter @lawilsonco

(All images reproduced with kind permission from the author)

By Tamsin Grainger

Edinburgh

February 2022

In the early hours, I look through the glass without seeing. I recognise the familiar butterfly-flutter, a movement in my abdomen, and instinctively curl over into a foetal position. Had I looked down onto the narrow, garden path, I might have seen the baby in the pram sleeping soundly, though my daughter was not yet born.

In the past, in my early 20s, there was a mistake. My periods ceased, my body got on with busying itself for the job it was destined for. I was horrified, felt inadequate, unready. There was no question what I had to do, though the Catholic doctor needed persuading and a second signature had to be sought. Afterwards, womb empty and breasts full, I felt like a crocodile which tried to haul itself out of the mire and got stranded. I didn’t know how being left with the loss would be. Bereft. Later, I told my grandmother, ‘I will never have children, I will never bring children into this ungrateful and terrible world’ and I saw her weeping silently. I turned and stared out of the car window, and ignored her sorrow.

It isn’t long before I sense the moist, folded limbs forming, and then I see them, opaque in the photograph, the veins a lattice with no colour or substance. I understand what form she will take. My corpuscles spiral through her; she lives from me. We thrive privately, she, spooned inside me.

In the night, through the ages, my great grandmother called to me. She was a midwife who crossed the moors come-rain-come-shine, come-day-come-night when she received a call. I saw her entering a cottage and stoop under the wooden lintel. I heard her coax a foundling into cold air, ‘Coo, come on, my beauty’, and then I saw that the drapes were being drawn and the wreath being hung on the door, and I knew that the mother, bled white, had stayed in this world only long enough to deliver her helpless babe. The nurturing she could do, was done; no-one in those days could stem the blood as she drained and so, she slid away.

At term, I crawl on all fours. I descend into myself, listen to the great, deep creaking of my body opening, preparing. I imagine curtains flung to reveal sunshine on the garden grass and see camouflage shadows on the lawn. Then, gaping, the movement stops.

I have to fight for them to hear me, to be believed. Finally, they administer the anaesthetic. I wait – doze – regroup - and then there’s the long slog. Inch by grinding inch, head down, my daughter turns. Feet braced on the hips of solid others, I labour, and when the doctor enters, brandishing metal and warning, I find a mighty strength and at last she is born. It is morning. Such joy.

As that girl-child in that long-ago cottage slipped between thighs, she was gathered into my great-grandmother’s arms and swaddled. That unknown baby already had ovaries full of eggs, and knowledge which had been passed through the pulsing generations, bringing with it the instinct to coddle and wheedle, raise and cosset, should she live to bear children herself. The cutting of the cord had severed her from the only human she had ever known. She knew that the breast from which she suckled was not the right one, and she waa-waa-cried with the wrongness of it all.

Forty-eight periods after, breast-feeding is over, my toddler is at hand, and we make the announcement. Another pregnancy - what repeating, unsuspecting happiness!

Fewer ages before me, my mother’s mother set off across the sea to Africa, obliged to rejoin her husband, her new-born daughter left behind. That baby was nurtured, professionally, by a nurse in an attic room above floors of growing girls in dorms. She remembers, when she was three years old, the sirens sounding along deserted streets and the whine of the doodlebug falling. Then, she told me, they cowered beneath tables or traipsed underground to huddle together, to bed down in rows. Lying awake and looking up at the hollow, sooty tunnel, she heard the clangs reverberating along temporarily disused tube-train rails, and I imagine how she raised herself onto one elbow and looked into the black hole, but could see nothing. I know now that she learned to be fearful, accepting and biddable, and she didn’t recognise the woman who returned to claim her from the Cape of Good Hope.

One morning a heavy door slams on me, knocks me over, shocks me profoundly, and I weep with a friend. I say, ‘What if…. .’ Looking back, I must have known.

Now I am left alone. It’s a loss that can never be fathomed, not if you haven’t felt the heave and squirm inside you. There in the kitchen, my belly a cavern and 'Fare Thee Well' blasting out from the radio, I surprise myself. I drop to the floor and hear myself howling. I keen and wail, for me and for all the mothers everywhere, for all who know, all around the world, all species, through the ages.

5000 miles away in the African savanna, east of the place where I was conceived, an elephant stands on four strong legs. As she hears my distant cry, she raises her trunk to the sky and bellows, she trumpets for the calf lying at her feet without tusks.

This tremendous moan carries across the desert as far as the Iberian Peninsula where a woman lays a stone at the foot of the Cruz de Ferro, the iron cross, in remembrance of her three-year-old son.

As her tears fall, in that place amongst the incalculable others, the geological strata itself, on which a billion pilgrims have trodden, recognises the grief of millennia.

This ululation ricochets all the way to the Pentland Hills where the pitiable bleating of ewes parted from their lambs can be heard even by those who stop their ears, for the yearning is terrible to hear.

And in the deepest waters of the Great Glen, 200 miles further north, the monster lies in the depths of Loch Ness and feels the vibration of a heart breaking. The accumulated waters - more than all the lakes in England and Wales put together - are not enough to assuage her own lament as she rises through the surface, cascades of water falling, and makes the sound of a thousand bagpipes droning.

That plaintive dirge surges over pine and yew, and nothing can prevent that dreadful sound echoing back to me, on my bleeding knees.

Only, nothing can bring back my baby.

The quietest elegy emerges from the she-whales in the deepest oceans; through the air can be heard the requiem of the barren. The earth sobs.

The tremors of the funeral processions passed through the generations. My mother knew it: that wide open mouth with no voice, that hollow windpipe with no-breath, the sinking feeling that comes from losing your child.

After the door slams shut, it is as if I live in an absence of sound. There is an aching in the space between my pubic bones which had already moved aside for the birth. I lie in the bath and look at the mound, the dome of pre-pregnant emptiness and absent issue. For twelve weeks, I had harboured that infant who would never look up at the halo around my head, mouthing my breast, warm milk spurting down her gullet.

The baby-that-was-me was put in the carry cot at the bottom of the garden. My wrongly-timed cries betrayed a cavernous hunger and my mother said she couldn’t bear it. ‘It is best ignored, because her need must not be satisfied before the predetermined time’, said the man who wrote a book which denied the child food and the mother the feeding - for reasons now insupportable.

So, I walk. In the jungle where the sawn-off stumps gape raw, have splintered because the mighty palms toppled and tore, under a sky where the canopy should have been. I watch an ant who is separated from the others in the column she has been following - instinctual, her job predetermined; I watch as she turns on a horizontal axis and does not know which way is front.

The wind that reaches me in that place seems to have already passed through the ruins and rubble of the hearths the midwife attended with hot kettle and rags, wailed across the seas my grandmother had sailed, blown between the walls of the hospitals where my mother and I began our lives. And so, the realisation comes at last, painfully: some are born, others die, some live, many do not. This is the lot of the female, this is our inheritance.

At the top of the sacred mountain, I can see behind me and all around, my past, my present, my future. In a silent forest, I walk. The humus is dark brown, the rotting loam pungent. I crouch down and dig into the layers where shoots and stems underneath are preparing for spring. I stand, lift my fingers to my face and inhale the rich compost behind my nails. I look up to the sky. One by one, I watch the leaves falling, meandering, swaying, and landing, soundlessly.

These days my ears ring - a high-pitched keening unheard by anyone else. I imagine the soundwaves vibrating through my internal waters, travelling around my cranium and down the deepest channel of my spine, transmitting messages. And back. A call is sent and received as I listen down the ages. My uterus fills with lifeless masses which cause my belly to swell to a three-month size, my breasts are still rounded, uselessly.

Now I am not alone. I have two daughters and I am connected. I am one of the women who link arms and make a line across the boulevard, wave after wave of women marching forwards, filling the streets. I am beside the others, those who fear for their lives, the lives of their children and babies. Young and old, we crowd into the square. We step in front of horses, lie down in the path of the juggernauts, chain ourselves to the railings. We stand, back-to-back on the tops of the Seven Hills, so that, together, we can see everywhere. And we tip our heads up to the moon and howl.

Tamsin first trained as a dancer and was the Dance Artist in Residence for the Forest of Dean and Edinburgh. For over 30 years she has been a Shiatsu practitioner, teacher, and is the author of ‘Death and Loss in Shiatsu Practice, a guide to holistic bodywork in palliative care’ which was published in 2020 by Singing Dragon (Hachette). She runs Death Cafes and online self-help sessions for people who are grieving. More recently, she has been writing creative non-fiction and memoir.

Tamsin likes to walk long-distance secular pilgrimages, to drift with a twitter group on Sunday mornings, amble around the city, join as many walking projects as she can, traverse cycle paths, cross beaches, and wander in her dreams. She writes about these walks and what she finds to touch, taste and smell, and she takes a lot of photos to put them in her blogs at walkingwithoutadonkey.com.

Her community walking projects include ‘Walk This Weekend’ and ‘Walking Between Worlds’. The latter celebrated women buried in Leith graveyards for the Audacious Women Festival.

Tamsin’s art work includes the installation, ‘No Birds Land’, and the mixed media exhibitions, ‘Clipp’d Wings’, with short films on Vimeo. She also held an online Tea Ceremony and Death Walk as part of art.earth’s Borrowed Time in 2021.

She is 58 years old and the proud mother of two grown-up daughters.

You can find Tamsin on twitter @WalkNoDonkey or instagram @tamsinshiatsu (image credit: Roger Jan)

By Amanda Edmiston

Scotland

January 2022

I've been forming, creating and collecting my whole life, but it came together and became Botanica Fabula eleven years ago. Knitting my own job, if you like! Finding folklore and traditional tales that share the way we use plants, and then collecting and sharing the plants from the stories to add another layer and weaving them into new tales, story-mending fragments of lore into my work to allow them to grow and retain relevance.

Stories naturally offer us an opportunity to reveal new chapters of our lives, whilst also connecting us deeply to the natural world. This weaving of the inherent nature and healing benefits of plants into a weft of words is, I suspect, a vital art and one that people need at a visceral level, offering us the deep understanding held within stories that allows us to reflect on life and change our own narrative as we approach new challenges, combined with the healing or life-enhancing abilities of plants, that give us what we need to enact that adaption.

Some of the time, I feel I ought to justify my herbal storytelling, explain what can happen with stories; maybe use terms like creative visualisation or guided imagery. For those who need it, these justifications offer a rational language to explain how my herbal storytelling works. Oral storytelling changes organically. Modern terms can coil in like tenuous, spiralling, tendrils of passiflora, allowing stories to remain relevant and vibrant for new audiences as language and understanding changes.

The vivid description of the effects of the plant is integral to many of my stories, offering a glimpse into an oral herbal guide. I feel this is often how the stories were told originally. Something almost magical can happen as listeners are held in a moment imagining the plant, imagining the changes taking place within the story, being drawn to find the plant, should they need to, after hearing the story, but also connecting as they listen, to the plants action within the tale. Part of me wants to retain this mesmer, not academicise it or justify it in a scientific manner.

I feel I risk explaining it away, in the same way the ethereal will’o the wisp became mere marsh gas, once a sybil's torch, a haunting hand guiding the careless traveller astray, becoming simply an antediluvian fart if scientifically justified, it's power and beauty lost. Sometimes, we just need to hold onto the magic, it helps us cope with difficult times.

In a way, this wildness, this hint of magic and natural chance for engagement a story offers, is a vital part of the plants power. It risks being lost when laws demand that herbal medicine falls in line with the world of manmade pharmaceuticals, a world of standardised extracts, where everything has a financial value; a world of decimated wild spaces, where people fear things they cannot immediately place and often lack time-tested knowledge. Through legends and folklore, the stories can offer a safe place to venture into and take a sip, to taste the fizzing potential of the power of plants -- a flower remedy-style dose of plant magic administered through a storyteller's art.

So I'd like to share a story with you now, one I wrote to story-mend a piece of folklore. A story, offered up by a mermaid, which advises us to turn to the first nettles when Spring approaches, mineral rich to strengthen us after we have endured winter, and to dream with hormone-balancing Mugwort as Summer beckons. For now, it invites you to reflect on the hidden knowledge, the potential to change your own narrative, to connect to plants and to hopefully enjoy a little look at a wild herbal story!

It’s said Salmon-tailed merfolk once wintered on the silt-strewn banks of Glasgow’s River Clyde.

They could take on legged form wandering the earth, but often found human folk aggressive and loud.

As the focus of man’s attentions became money and manufacture they began to drift to deeper water.

Until just one Merrow woman remained in the Clyde’s tidal flow. Watching as her treasured green place turned to dirt and greed, ‘til folks could no longer hear her sing.

Industry gained momentum, tenements, back-to-back, dark and damp covered the meadows.

Shipyards called for the river to be dredged.

Banks were clawed, forests burnt.

People living foreshortened lives.

Nowhere could be found the iron-rich greens which brought riches to the body, now only iron filled yards brought riches to the few.

The mermaid sensed a world in which she was no longer welcome, leaving this heat-arced world she muttered ‘if they ate Nettles in March and Mugworts in May not so many good maidens would have gone to the clay.’

Her words floating downriver, tide washing in, drifting out, moon pulling water away.

As we gather Nettles in our dock covered hands, inhaling Mugwort’s bitter aroma as Spring arrives, we hope she swims well-nourished amidst Kelp beds, waiting for a time to return as the meadows start moving back to the abandoned ship-yards.

Amanda Edmiston (Botanica Fabula) is a professional storyteller, writer and artist with a background in herbal medicine, based in Scotland. She has a passion for creating and retelling stories laced with traditional herbal remedies, designed to draw her audience further into the enchanted world of plants. She has created work for Chelsea Physic Garden in London, The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, and The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford amongst others, and has worked with schools, museums and festivals around the world both online and in-person. She is currently working on The Very Curious Herbal Project which you can catch up with as a podcast and Handing On, a project with her mum Jean Edmiston, an artist and professional storyteller for over 30 years. As part of this, the pair are creating workshops and mentoring opportunities, live and online for those considering adding a bit of herbal storytelling magic to their own creative practice!

(photo copyright 2020 - John Ritchie)

WILD WOMEN PRESS

CONTACTS

Email: vik@wildwomenpress.com